(Press-News.org) Proteins that form clumps occur in many difficult-to-treat diseases, such as ALS, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson's. The mechanisms behind how the proteins interact with each other are difficult to study, but now researchers at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, have discovered a new method for capturing many proteins in nano-sized traps. Inside the traps, the proteins can be studied in a way that has not been possible before.

"We believe that our method has great potential to increase the understanding of early and dangerous processes in a number of different diseases and eventually lead to knowledge about how drugs can counteract them," says Andreas Dahlin, professor at Chalmers, who led the research project.

Proteins that form clumps in our bodies cause a large number of diseases, including ALS, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. A better understanding of how the clumps form could lead to effective ways to dissolve them at an early stage, or even prevent them from forming altogether. Today, there are various techniques for studying the later stages of the process, when the clumps have become large and formed long chains, but until now it has been difficult to follow the early development, when they are still very small. These new traps can now help to solve this problem.

Can study higher concentrations for longer time

The researchers describe their work as the world's smallest gates that can be opened and closed at the touch of a button. The gates become traps, that lock the proteins inside chambers at the nanoscale. The proteins are prevented from escaping, extending the time they can be observed at this level from one millisecond to at least one hour. The new method also makes it possible to enclose several hundred proteins in a small volume, an important feature for further understanding.

"The clumps that we want to see and understand better consist of hundreds of proteins, so if we are to study them, we need to be able to trap such large quantities. The high concentration in the small volume means that the proteins naturally bump into each other, which is a major advantage of our new method," says Andreas Dahlin.

In order for the technique to be used to study the course of specific diseases, continued development of the method is required.

"The traps need to be adapted to attract the proteins that are linked to the particular disease you are interested in. What we're working on now is planning which proteins are most suitable to study," says Andreas Dahlin.

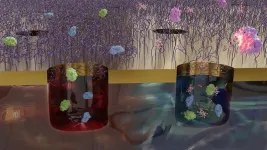

How the new traps work

The gates that the researchers have developed consist of so-called polymer brushes positioned at the mouth of nano-sized chambers. The proteins to be studied are contained in a liquid solution and are attracted to the walls of the chambers after a special chemical treatment. When the gates are closed, the proteins can be freed from the walls and start moving towards each other. In the traps, you can study individual clumps of proteins, which provides much more information compared to studying many clumps at the same time. For example, the clumps can be formed by different mechanisms, have different sizes and different structures. Such differences can only be observed if one analyses them one by one. In practice, the proteins can be retained in the traps for almost any length of time, but at present, the time is limited by how long the chemical marker - which they must be provided with to become visible - remains. In the study, the researchers managed to maintain visibility for up to an hour.

The research has been presented in the scientific article "Stable trapping of multiple proteins at physiological conditions using nanoscale chambers with macromolecular gates" recently published in Nature Communications.

The article is written by Justas Svirelis, Zeynep Adali, Gustav Emilsson, Jesper Medin, John Andersson, Radhika Vattikunta, Mats Hulander, Julia Järlebark, Krzysztof Kolman, Oliver Olsson, Yusuke Sakiyama, Roderick Y. H. Lim and Andreas Dahlin. The researchers are active at Chalmers University of Technology and the University of Basel.

Illustration credit: Chalmers University of Technology | Julia Järlebark

Image caption: The image shows the protein traps, which consist of nanoscale chambers and polymers that form gates above. These “doors” are opened up by increasing the temperature by about 10 degrees, which is done electrically. Then the polymers change their shape to a more compact state so that proteins can pass in and out.

END

Tiny traps can provide new knowledge about difficult-to-treat diseases

2023-11-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Infection-resistant, 3D-printed metals developed for implants

2023-11-20

PULLMAN, Wash. – A novel surgical implant developed by Washington State University researchers was able to kill 87% of the bacteria that cause staph infections in laboratory tests, while remaining strong and compatible with surrounding tissue like current implants.

The work, reported in the International Journal of Extreme Manufacturing, could someday lead to better infection control in many common surgeries, such as hip and knee replacements, that are performed daily around the world. Bacterial colonization of the implants is one of the leading causes of their failure and bad outcomes after surgery.

“Infection ...

Hidden belly fat in midlife linked to Alzheimer’s disease

2023-11-20

CHICAGO – Higher amounts of visceral abdominal fat in midlife are linked to the development of Alzheimer’s disease, according to research being presented next week at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA). Visceral fat is fat surrounding the internal organs deep in the belly. Researchers found that this hidden abdominal fat is related to changes in the brain up to 15 years before the earliest memory loss symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease occur.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, there are ...

New treatment restores sense of smell in patients with long COVID

2023-11-20

CHICAGO – Using an image-guided minimally invasive procedure, researchers may be able to restore the sense of smell in patients who have suffered with long-COVID, according to research being presented next week at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

Parosmia, a condition where the sense of smell no longer works correctly, is a known symptom of COVID-19. Recent research has found that up to 60% of COVID-19 patients have been affected. While most patients do recover their sense of smell over time, some patients with long COVID continue to have these symptoms for months, or even years, after ...

Why do some people get headaches from drinking red wine?

2023-11-20

A red wine may pair nicely with the upcoming Thanksgiving meal. But for some people, drinking red wine even in small amounts causes a headache. Typically, a “red wine headache” can occur within 30 minutes to three hours after drinking as little as a small glass of wine.

What in wine causes headaches?

In a new study, scientists at the University of California, Davis, examined why this happens – even to people who don’t get headaches when drinking small amounts of other alcoholic beverages. Researchers think that a flavanol found naturally in red wines can interfere with the proper metabolism of alcohol and can lead to a headache. The study was published in ...

Mental health of surfers creates US$1trillion wave for economy

2023-11-20

New research led by Griffith University on Australia’s Gold Coast and Andrés Bello University in Chile, has shown that surfing contributes about US$1 trillion a year to the global economy, by improving the mental health of surfers.

For the Gold Coast alone, the research team estimated the benefits to be valued at ~US$1.0–3.3 billion per year. Mental health benefits from surfing comprise 57–74% of the total economic benefits of surfing. The mental health benefits are 4.4–13.5 times direct expenditure by surfers, and 4–12 times economic effects via property and inbound tourism.

The research ...

Proof of concept of new material for long lasting relief from dry mouth conditions

2023-11-20

Proof of concept of new material for long lasting relief from dry mouth conditions

A novel aqueous lubricant technology designed to help people who suffer from a dry mouth is between four and five times more effective than existing commercially available products, according to laboratory tests.

Developed by scientists at the University of Leeds, the saliva substitute is described as comparable to natural saliva in the way it hydrates the mouth and acts as a lubricant when food is chewed.

Under a powerful microscope, the molecules in the substance - known as a microgel - appear as a lattice-like ...

Innovative aquaculture system turns waste wood into nutritious seafood

2023-11-20

PRESS RELEASE FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE

EMBARGOED UNTIL 10:00 LONDON TIME (GMT) ON 20 NOVEMBER, 2023

[Photographs and a copy of the paper are available here]

These long, white saltwater clams are the world’s fastest-growing bivalve and can reach 30cm long in just six months. They do this by burrowing into waste wood and converting it into highly-nutritious protein.

The researchers found that the levels of Vitamin B12 in the Naked Clams were higher than in most other bivalves – and almost twice the amount found in blue mussels.

And with the addition of an algae-based feed to the system, the Naked Clams can be fortified with omega-3 polyunsaturated ...

Our cerebellar nuclei turn out to be more important than initially thought

2023-11-20

Associative learning was always thought to be regulated by the cortex of the cerebellum, often referred to as the “little brain". However, new research from a collaboration between the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, Erasmus MC, and Champalimaud Center for the Unknown reveals that actually the nuclei of the cerebellum make a surprising contribution to this learning process.

If a teacup is steaming, you’ll wait a bit longer before drinking from it. And if your fingers get caught in the door, you'll be more careful next time. These are forms of associative ...

Liver cancer rates are rising with each successive generation of Mexican Americans

2023-11-20

New research reveals that with each subsequent generation of Mexican Americans, the risk of developing liver cancer has climbed. Although Mexican Americans have experienced a growing trend in modifiable risk factors—such as increased alcohol consumption, higher smoking rates, and elevated body mass index—these factors alone do not entirely account for the increased risk of liver cancer as generations progress. The findings are published by Wiley online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

US-born Latinos have a higher incidence of liver cancer than foreign-born Latinos, and a possible ...

Liver cancer rates increase in each successive generation of Mexican Americans, study finds

2023-11-20

In the United States, liver cancer rates have more than tripled since 1980. Some groups, including Latinos, face an even higher risk than the general population—but researchers do not fully understand why.

A study from the Keck School of Medicine of USC, funded by the National Cancer Institute, has shed new light on those disparities. Researchers found that among Mexican Americans, liver cancer risk rises the longer a person’s family has lived in the U.S. That increased risk primarily affected men. The ...