(Press-News.org) When you eagerly dig into a long-awaited dinner, signals from your stomach to your brain keep you from eating so much you’ll regret it – or so it’s been thought. That theory had never really been directly tested until a team of scientists at UC San Francisco recently took up the question.

The picture, it turns out, is a little different.

The team, led by Zachary Knight, PhD, a UCSF professor of physiology in the Kavli Institute for Fundamental Neuroscience, discovered that it’s our sense of taste that pulls us back from the brink of food inhalation on a hungry day. Stimulated by the perception of flavor, a set of neurons – a type of brain cell – leaps to attention almost immediately to curtail our food intake.

“We’ve uncovered a logic the brainstem uses to control how fast and how much we eat, using two different kinds of signals, one coming from the mouth, and one coming much later from the gut,” said Knight, who is also an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and a member of the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences. “This discovery gives us a new framework to understand how we control our eating.”

The study, which appears Nov. 22, 2023 in Nature, could help reveal exactly how weight-loss drugs like Ozempic work, and how to make them more effective.

New views into the brainstem

Pavlov proposed over a century ago that the sight, smell and taste of food are important for regulating digestion. More recent studies in the 1970s and 1980s have also suggested that the taste of food may restrain how fast we eat, but it’s been impossible to study the relevant brain activity during eating because the brain cells that control this process are located deep in the brainstem, making them hard to access or record in an animal that’s awake.

Over the years, the idea had been forgotten, Knight said.

New techniques developed by lead author Truong Ly, PhD, a graduate student in Knight’s lab, allowed for the first-ever imaging and recording of a brainstem structure critical for feeling full, called the nucleus of the solitary tract, or NTS, in an awake, active mouse. He used those techniques to look at two types of neurons that have been known for decades to have a role in food intake.

The team found that when they put food directly into the mouse’s stomach, brain cells called PRLH (for prolactin-releasing hormone) were activated by nutrient signals sent from the GI tract, in line with traditional thinking and the results of prior studies.

However, when they allowed the mice to eat the food as they normally would, those signals from the gut didn’t show up. Instead, the PRLH brain cells switched to a new activity pattern that was entirely controlled by signals from the mouth.

“It was a total surprise that these cells were activated by the perception of taste,” said Ly. “It shows that there are other components of the appetite-control system that we should be thinking about.”

While it may seem counterintuitive for our brains to slow eating when we’re hungry, the brain is actually using the taste of food in two different ways at the same time. One part is saying, “This tastes good, eat more,” and another part is watching how fast you’re eating and saying, “Slow down or you’re going to be sick.”

“The balance between those is how fast you eat,” said Knight.

The activity of the PRLH neurons seems to affect how palatable the mice found the food, Ly said. That meshes with our human experience that food is less appetizing once you’ve had your fill of it.

Brain cells that inspire weight-loss drugs

The PRLH-neuron-induced slowdown also makes sense in terms of timing. The taste of food triggers these neurons to switch their activity in seconds, from keeping tabs on the gut to responding to signals from the mouth.

Meanwhile, it takes many minutes for a different group of brain cells, called CGC neurons, to begin responding to signals from the stomach and intestines. These cells act over much slower time scales – tens of minutes – and can hold back hunger for a much longer period of time.

“Together, these two sets of neurons create a feed-forward, feed-back loop,” said Knight. “One is using taste to slow things down and anticipate what’s coming. The other is using a gut signal to say, ‘This is how much I really ate. Ok, I’m full now!’”

The CGC brain cells’ response to stretch signals from the gut is to release GLP-1, the hormone mimicked by Ozempic, Wegovy and other new weight-loss drugs.

These drugs act on the same region of the brainstem that Ly’s technology has finally allowed researchers to study. “Now we have a way of teasing apart what’s happening in the brain that makes these drugs work,” he said.

A deeper understanding of how signals from different parts of the body control appetite would open doors to designing weight-loss regimens designed for the individual ways people eat by optimizing how the signals from the two sets of brain cells interact, the researchers said.

The team plans to investigate those interactions, seeking to better understand how taste signals from food interact with feedback from the gut to suppress our appetite during a meal.

Co-authors: Nilla Sivakumar, Zhengya Liu, Naz Dundar, Brooke C. Jarvie, Anagh Ravi, Olivia K. Barnhill and Heeun Jang of UCSF and Jun Y. Oh, Sarah Shehata, Naymalis La Santa Medina, Heidi Huang, Wendy Fang, Chris Barnes, Chelsea Li, Grace R. Lee and Jaewon Choi of HHMI.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants (R01-DK106399, F31DK137586).

About UCSF: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is exclusively focused on the health sciences and is dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. UCSF Health, which serves as UCSF's primary academic medical center, includes top-ranked specialty hospitals and other clinical programs, and has affiliations throughout the Bay Area. UCSF School of Medicine also has a regional campus in Fresno. Learn more at https://ucsf.edu, or see our Fact Sheet.

###

Follow UCSF

ucsf.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

END

From the first bite, our sense of taste helps pace our eating

Brainstem recording shows that our tastebuds are the first line of defense against eating too fast. Understanding how may lead to new avenues for weight loss.

2023-11-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Team discovers rules for breaking into Pseudomonas

2023-11-22

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Researchers report in the journal Nature that they have found a way to get antibacterial drugs through the nearly impenetrable outer membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a bacterium that – once it infects a person – is notoriously difficult to treat.

By bombarding P. aeruginosa with hundreds of compounds and using machine learning to determine the physical and chemical traits of those molecules that accumulated inside it, the team discovered how to penetrate the bacterium’s defenses. They used this information ...

Camouflaging stem cell-derived transplants avoids immune rejection

2023-11-22

Cell and organ transplants can be lifesaving, but patients often encounter long waiting lists due to the shortage of suitable donors. According to donatelife.net, in 2021 6,000 people died in the U.S. alone while waiting for a transplant. One day, transplants generated from stem cells may alleviate the constant organ donor shortage, making transplants available to a larger group of patients.

An issue with donation, whether it’s with solid tissues or cells from deceased or living donors, is immune rejection. Unless the donor material is carefully matched to the recipient’s immune system, the transplant will be rejected. However, stem cell research ...

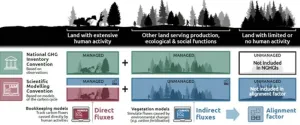

Mind the gap: Caution needed when assessing land emissions in the COP28 Global Stocktake

2023-11-22

Effective management of land, whether for agriculture, forests, or settlements, plays a crucial role in addressing climate change and achieving future climate targets. Land use strategies to mitigate climate change include stopping deforestation, along with enhancing forest management efforts. Countries have recognized the importance of the land use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF) sector, with 118 of 143 countries including land-based emissions reductions and removals in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), which are at the heart of the Paris Agreement and the achievement of its long-term goals.

A new study, published in Nature, demonstrates that estimates of current land-based ...

Developing a new perspective for the EU beekeeping sector: B-GOOD legacy booklet

2023-11-22

The aim of the B-GOOD project (Giving Beekeeping Guidance By Computational-Assisted Decision Making) was to pave the way towards healthy and sustainable beekeeping within the European Union by following a collaborative and interdisciplinary approach. By merging data from within and around beehives, as well as wider socioeconomic conditions and by developing and testing innovative tools to perform risk assessments, B-GOOD provided guidance for beekeepers and helped them make better and more informed decisions.

The communication of scientific information and the transformation of scientific ...

How do temperature extremes influence the distribution of species?

2023-11-22

As the planet gets hotter, animal and plant species around the world will be faced with new, potentially unpredictable living conditions, which could alter ecosystems in unprecedented ways. A new study from McGill University researchers, in collaboration with researchers in Spain, Mexico, Portugal, Denmark, Australia, South Africa and other universities in Canada, investigates the importance of temperature in determining where animal species are currently found to better understand how a warming climate ...

New remote sensing dataset improves global land change tracking

2023-11-22

Tracking unprecedented changes in land use over the past century, global land cover maps provide key insights into the impact of human settlement on the environment. Researchers from Sun Yat-sen University created a large-scale remote sensing annotation dataset to support Earth observation research and provide new insight into the dynamic monitoring of global land cover.

In their study, published Oct 16 in the Journal of Remote Sensing, the team examined how global land use/landcover (LULC) has undergone dramatic changes with the advancement of industrialization and urbanization, including deforestation and flooding.

“We ...

A Special Collection collaboration between SLAS and SBI2

2023-11-22

Oak Brook, IL – The latest issue of SLAS Discovery is a joint Special Collection between SLAS and the Society of Biomolecular Imaging and Informatics (SBI2) to celebrate the 10th Annual SBI2 High-Content Imaging and Informatics meeting. This collaboration features a curated special collection of articles that highlight the significant impact of high-content imaging in basic and translational research. Volume 28, Issue 7 features one perspective, four original research articles and one short communication.

Perspective

Evolution and Impact of High Content Imaging

This ...

A new diagnostic tool to identify and treat pathological social withdrawal, Hikikomori

2023-11-22

Fukuoka, Japan—Researchers at Kyushu University have developed a new tool to help clinicians and researchers assess individuals for pathological social withdrawal, known as Hikikomori. The tool, called Hikikomori Diagnostic Evaluation, or HiDE, can be a practical guide on collecting information on this globally growing pathology.

Hikikomori is a condition characterized by sustained physical isolation or social withdrawal for a period exceeding six months. It was first defined in Japan in 1998, ...

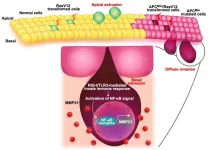

Survival of the fittest? New study shows how cancer cells use cell competition to evade the body’s defenses

2023-11-22

Living cells compete with each other and try to adapt to the local environment. Cells that are unable to do so are eliminated eventually. This cellular competition is crucial as the surrounding normal epithelial cells use it to identify and eliminate mutant cancer cells. Studies have reported that when activating mutants of “Ras” proteins are expressed in mammalian epithelial cells, they are pushed toward the lumen, excreted along with other bodily waste, and eliminated by competition. Epithelial cells containing Ras mutants have been reported to be removed in this manner in several organs, including the small intestine, stomach, pancreas, and lungs. ...

Danish researchers puncture 100-year-old theory of odd little 'water balloons'

2023-11-22

Quinoa and many other extremely resilient plants are covered with strange balloon-like 'bladders' that for 127 years were believed to be responsible for protecting them from drought and salt. Research results from the University of Copenhagen reveal this not to be the case. These so-called bladder cells serve a completely different though important function. The finding makes it likely that even more resilient quinoa plants will now be able to be bred, which could lead to the much wider cultivation of this sustainable ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

RESPIN launches new online course to bridge the gap between science and global environmental policy

Electric field tunes vibrations to ease heat transfer

[Press-News.org] From the first bite, our sense of taste helps pace our eatingBrainstem recording shows that our tastebuds are the first line of defense against eating too fast. Understanding how may lead to new avenues for weight loss.