(Press-News.org) SAN FRANCISCO—November 30, 2023—When women with diabetes become pregnant, they face not only the typical challenges of pregnancy and impending parenthood, but also a scary statistic: they’re five times more likely to have a baby with a congenital heart defect.

Researchers at Gladstone Institutes have now discovered why that is, identifying the cells and molecules that go awry in the developing hearts of fetuses in women with diabetes. They found that a small subset of cells destined to become part of the heart’s aorta and pulmonary artery have unusually high levels of retinoic acid activity, which coaxes them to behave more like cells found elsewhere in the heart.

The study, carried out in mice and published in Nature Cardiovascular Research, could eventually lead to interventions that lower the chance of heart malformations in babies born to women with diabetes. It also paves the way toward similar research on diverse array of other poorly understood birth defects.

“There are a number of environmental factors, including maternal diabetes, that we know are associated with birth defects, but we haven’t been able to understand the mechanisms until now,” says Gladstone President and Senior Investigator Deepak Srivastava, MD, the senior author of the new study. “This kind of modern, single-cell study can reveal these mechanisms and, ultimately, help us design therapeutic interventions to lower the risk of birth defects.”

Srivastava is also director of Gladstone’s Roddenberry Stem Cell Center and a professor of Pediatrics and of Biochemistry & Biophysics at the UC San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center.

Millions of Heart Cells

In mice and human embryos alike, millions of cells must respond to precise chemical signals, each at the right place and right time, to create a beating heart. If even a few embryonic cells receive the wrong molecular signals, the heart or nearby blood vessels can develop incorrectly, leading to congenital heart defects. But due to the vast number and complexity of cells, pinning down what went wrong in any individual case of congenital heart disease is daunting.

“Congenital heart disease is the most common birth defect and comes with a huge social burden—it can be absolutely devastating for patients and their families,” says Tomohiro Nishino, MD, PhD, a Gladstone postdoctoral scholar and first author of the study. “But without understanding the precise causes of these defects, there is really nothing we can do to prevent it.”

Researchers do know that one of the most common non-genetic causes of congenital heart defects is maternal type I or type II diabetes before conception. These forms are distinct from gestational diabetes, which develops later in pregnancy, usually after a baby’s heart has formed.

To learn how maternal diabetes contributes to heart defects, Srivastava’s lab turned to a model of diabetic mice with high rates of heart defects in their offspring. The researchers collected more than 30,000 different cells from the developing hearts of embryos growing in the diabetic mice. Then, the researchers analyzed both the three-dimensional configuration of DNA and the levels of different mRNA molecules in each individual cell, which encode for proteins. Together, the experiments paint a picture of how genetic material is being used by the cells to dictate their functions.

“Coupling these two types of data let us determine not only how the cells are different when a fetus is exposed to maternal diabetes, but also what might be regulating that change,” explains Srivastava.

A Molecular Trigger

When the researchers looked at how DNA was packaged into its tight three-dimensional structure—which gives hints about which parts of the DNA molecule are being actively used by a cell—Srivastava’s group found more than 4,000 differences between mice that are developing normally and those exposed to maternal diabetes. Surprisingly, 97 percent of the differences were in two small subsets of cells, one of which goes on to form a critical section of the heart separating the aorta and pulmonary artery and chambers of the heart, and the other involved in facial development, another area affected in maternal diabetes. The subset of heart cells affected had higher-than-usual activity in a gene called ALX3, which controls the activity of many other genes.

“This subset of cells was never previously recognized as being different than the cells around it, so it was quite surprising to discover that those cells were so selectively vulnerable to maternal diabetes and responsible for the defects observed,” Srivastava says.

The team went on to show that this subset of cells had high activity levels of the molecule retinoic acid, which is itself known to cause birth defects. Usually, higher levels of retinoic acid are found only in cells in the lower, or posterior, part of the heart-forming region. In maternal diabetes, the more anterior heart precursor cells that contribute to the aorta and pulmonary artery regions were being induced to behave more like more posterior cells, likely causing the observed defects.

More research is needed to determine how maternal diabetes changes levels of retinoic acid, and why the newly discovered subset of heart cells is particularly susceptible to that increase. But the initial molecular understanding of what is triggering the heart defect offers a path forward.

The study also provides a template for how to use cutting-edge single-cell research to study links between environmental factors and birth defects more broadly. The same type of experiments could be used in other organ systems and for other exposures, such as drugs known to cause birth defects.

“The goal is eventually to have therapeutics that we can offer to mothers that lower their risk of all these birth defects,” Srivastava says.

About the Study

The paper “Single-cell multimodal analyses reveal epigenomic and transcriptomic basis for birth defects in maternal diabetes” was published in the journal Nature Cardiovascular Research on November 30, 2023. Other authors are: Sanjeev Ranade, Angelo Pelonero, Benjamin van Soldt, Lin Ye, Michael Alexanian, Frances Koback, Yu Huang, Nandhini Sadagopan, Adrienne Lam, Lyandysha Zholudeva, Feiya Li, Arun Padmanabhan, Reuben Thomas, Joke van Bemmel, Casey Gifford and Mauro Costa, all of Gladstone and UCSF.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (P01 HL146366, R01 HL057181, R01 HL015100, R01 HL127240, K08 HL157700), the Roddenberry Foundation, the L.K. Whittier Foundation, Dario and Irina Sattui, the Younger Family Fund, Additional Ventures, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Overseas Research Fellowship, an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (899270), the Sarnoff Cardiovascular Research Foundation, and the Michael Antonov Charitable Foundation.

About Gladstone Institutes

Gladstone Institutes is an independent, nonprofit life science research organization that uses visionary science and technology to overcome disease. Established in 1979, it is located in the epicenter of biomedical and technological innovation, in the Mission Bay neighborhood of San Francisco. Gladstone has created a research model that disrupts how science is done, funds big ideas, and attracts the brightest minds.

END

Gladstone team uncovers why maternal diabetes predisposes babies to heart defects

The cutting-edge research methods that led to the discovery could be used to find other connections between environmental factors and birth defects

2023-11-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

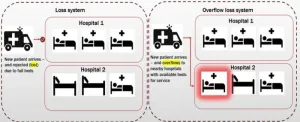

CityU researchers tackle a century-old teletraffic challenge to enhance medical and public service efficiency

2023-11-30

Efficiently meeting the growing demand for public services in metropolitan areas has long been a persistent challenge. A research team at City University of Hong Kong (CityU) has developed a novel performance evaluation method, which marks a major breakthrough in tackling a century-old problem of evaluating blocking probabilities in queueing systems with overflow, providing ways to allocate limited resources better. With the remarkable advances in computational efficiency and accuracy, the method has great potential to optimise the performance of numerous telecommunication networks and even medical care systems, ultimately enhancing ...

Bringing asteroids to class: COSPAR joins new Erasmus+ program

2023-11-30

COSPAR and the Erasmus+ Education Programme

COSPAR’s participation in Erasmus+ programmes is part of the COSPAR Panel on Education’s new approach to its mission of developing “means and media to encourage and spread space-related education”. The StudenTs As plaNetary Defenders (StAnD) project aims to engage primary and secondary school students in the subject of asteroids, meteors, and planetary defence.

The 36-month StudenTs As plaNetary Defenders (StAnD) programme brings asteroids, comets, meteors and meteorites to the classroom using carefully prepared activities and experiments. The programme includes the installation of meteor detection cameras in participating ...

Developing a superbase-comparable BaTiO3−xNy oxynitride catalyst

2023-11-30

Basic oxide catalysts contain oxygen ions with unpaired electrons that can be shared with other species to facilitate a chemical reaction. These catalysts are widely used in the synthesis of chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and petrochemicals. There have been efforts to improve the catalytic power of these catalysts by improving their basicity or the ability to donate electrons or accept hydrogen ions. Various strategies include doping the catalyst with highly electronegative cations such as alkali metals, substituting oxide ions ...

Hurricanes boost cone production in longleaf pine

2023-11-30

New research on tree reproduction is helping solve a puzzle that has stumped tree scientists for decades. Many tree species exhibit a reproductive phenomenon known as “masting”, where individual trees have very low seed production in most years followed by a sudden burst of seed production that is synchronized over large parts of its range. The reason for this coordinated reproduction within a species is unclear.

A new study by scientists at The Jones Center at Ichauway and the USDA Forest Service Southern Research Station showed ...

Scientists uncover how fermented-food bacteria can guard against depression, anxiety

2023-11-30

University of Virginia School of Medicine researchers have discovered how Lactobacillus, a bacterium found in fermented foods and yogurt, helps the body manage stress and may help prevent depression and anxiety. The findings open the door to new therapies to treat anxiety, depression and other mental-health conditions.

The new research from UVA’s Alban Gaultier, Ph.D., and collaborators is notable because it pinpoints the role of Lactobacillus, separating it out from all the other microorganisms that naturally live in and on our bodies. These organisms are collectively known as the microbiota, and scientists have increasingly ...

Broadband buzz: Periodical cicadas' chorus measured with fiber optic cables

2023-11-30

Annapolis, MD; November 30, 2023—Hung from a common utility pole, a fiber optic cable—the kind bringing high-speed internet to more and more American households—can be turned into a sensor to detect temperature changes, vibrations, and even sound, through an emerging technology called distributed fiber optic sensing.

However, as NEC Labs America photonics researcher Sarper Ozharar, Ph.D., explains, acoustic sensing in fiber optic cables "is limited to only nearby sound sources or very loud events, such as emergency vehicles, car alarms, or cicada emergences."

Cicadas? Indeed, periodical cicadas—the ...

More than $13M awarded to study childhood obesity interventions in rural and minority communities in Louisiana and Tennessee

2023-11-30

BATON ROUGE – Pennington Biomedical Research Center and Vanderbilt University Medical Center have received $13.8 million for five years of research funding from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute to study the ideal “dose” of behavioral interventions to treat childhood obesity in rural and minority communities across Louisiana and Tennessee.

Pennington Biomedical’s Amanda Staiano and Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Bill Heerman are co-principal investigators on the randomized, multisite trial.

Despite ongoing efforts, childhood obesity rates have continued to increase over the ...

Decoding past climates through dripstones

2023-11-30

“Dripstones, or speleothems, are unique natural archives - like Earth’s USB sticks. They store a wealth of information on past climate which helps us to better understand the environment in which early humans lived”, Jenny Maccali explains. She is a scientist at SapienCE Centre of Excellence, and has has lead the study, now published in Climate of the Past.

New perspective to ancient climate

South Africa has a highly dynamic climate resulting from its position at the convergence of two oceanic basins, the Atlantic Ocean to the west and the Indian Ocean to the east. ...

Lower voltage and reduced carbon input for cleaner energy in the works

2023-11-30

There is an ever-present struggle to reduce carbon-based energy sources and replace them with low or no-carbon alternatives. The process of splitting water could be the resolution.

Hydrogen production is a simple, safe, and effective method to produce more energy than gasoline can by the simple process of splitting water. Harvesting energy this way as opposed to relying heavily (or at all) on carbon-based energy sources is increasingly becoming the standard. Researchers have found a method to use transition metal ...

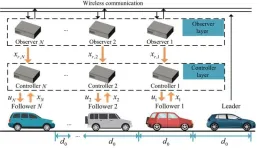

Platoon control of connected vehicles with heterogeneous model structures considering external disturbances

2023-11-30

A paper describing the distributed cooperative control problem with the heterogeneous model structures and external disturbances for the connected vehicle (CV) platoon was published in the journal Green Energy and Intelligent Transportation on November 25th, 2022.

In recent decades, the cooperative control problems of CV platoon on highways have attracted widespread interest for their significant impact on road transportation. The platoon control of CV has the advantages of improving the safety of highways, increasing the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Gibson Oncology, NIH to begin Phase 2 trials of LMP744 for treatment of first-time recurrent glioblastoma

Researchers develop a high-efficiency photocatalyst using iron instead of rare metals

Study finds no evidence of persistent tick-borne infection in people who link chronic illness to ticks

New system tracks blockchain money laundering faster and more accurately

In vitro antibacterial activity of crude extracts from Tithonia diversifolia (asteraceae) and Solanum torvum (solanaceae) against selected shigella species

Qiliang (Andy) Ding, PhD, named recipient of the 2026 ACMG Foundation Rising Scholar Trainee Award

Heat-free gas sensing: LED-driven electronic nose technology enhances multi-gas detection

Women more likely to choose wine from female winemakers

E-waste chemicals are appearing in dolphins and porpoises

Researchers warn: opioids aren’t effective for many acute pain conditions

Largest image of its kind shows hidden chemistry at the heart of the Milky Way

JBNU researchers review advances in pyrochlore oxide-based dielectric energy storage technology

Novel cellular phenomenon reveals how immune cells extract nuclear DNA from dying cells

Printable enzyme ink powers next-generation wearable biosensors

6 in 10 US women projected to have at least one type of cardiovascular disease by 2050

People’s gut bacteria worse in areas with higher social deprivation

Unique analysis shows air-con heat relief significantly worsens climate change

Keto diet may restore exercise benefits in people with high blood sugar

Manchester researchers challenge misleading language around plastic waste solutions

Vessel traffic alters behavior, stress and population trends of marine megafauna

Your car’s tire sensors could be used to track you

Research confirms that ocean warming causes an annual decline in fish biomass of up to 19.8%

Local water supply crucial to success of hydrogen initiative in Europe

New blood test score detects hidden alcohol-related liver disease

High risk of readmission and death among heart failure patients

Code for Earth launches 2026 climate and weather data challenges

Three women named Britain’s Brightest Young Scientists, each winning ‘unrestricted’ £100,000 Blavatnik Awards prize

Have abortion-related laws affected broader access to maternal health care?

Do muscles remember being weak?

Do certain circulating small non-coding RNAs affect longevity?

[Press-News.org] Gladstone team uncovers why maternal diabetes predisposes babies to heart defectsThe cutting-edge research methods that led to the discovery could be used to find other connections between environmental factors and birth defects