(Press-News.org) PRESS RELEASE FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE

EMBARGOED UNTIL 10 AM LONDON TIME (GMT) ON FRIDAY 1 DECEMBER 2023

Images and paper available at: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1JRhAD1ESL6NZN7acEoZQcXCA9w50Gczr?usp=drive_link

Phonetic information – the smallest sound elements of speech – may not be the basis of language learning in babies as previously thought

Babies don’t begin to process phonetic information reliably until seven months old – which researchers say is too late to form the foundation of language

Instead, babies learn from rhythmic information – the changing emphasis of syllables in speech – which unlike phonetic information, can be heard in the womb

Parents should speak to their babies using sing-song speech, like nursery rhymes, as soon as possible, say researchers. That’s because babies learn languages from rhythmic information, not phonetic information, in their first months.

Phonetic information – the smallest sound elements of speech, typically represented by the alphabet – is considered by many linguists to be the foundation of language. Infants are thought to learn these small sound elements and add them together to make words. But a new study suggests that phonetic information is learnt too late and slowly for this to be the case.

Instead, rhythmic speech helps babies learn language by emphasising the boundaries of individual words and is effective even in the first months of life.

Researchers from the University of Cambridge and Trinity College Dublin investigated babies’ ability to process phonetic information during their first year.

Their study, published today in the journal Nature Communications, found that phonetic information wasn’t successfully encoded until seven months old, and was still sparse at 11 months old when babies began to say their first words.

“Our research shows that the individual sounds of speech are not processed reliably until around seven months, even though most infants can recognise familiar words like ‘bottle’ by this point,” said Cambridge neuroscientist, Professor Usha Goswami. “From then individual speech sounds are still added in very slowly – too slowly to form the basis of language.”

The researchers recorded patterns of electrical brain activity in 50 infants at four, seven and eleven months old as they watched a video of a primary school teacher singing 18 nursery rhymes to an infant. Low frequency bands of brainwaves were fed through a special algorithm, which produced a ‘read out’ of the phonological information that was being encoded.

The researchers found that phonetic encoding in babies emerged gradually over the first year of life, beginning with labial sounds (e.g. d for “daddy”) and nasal sounds (e.g. m for “mummy”), with the ‘read out’ progressively looking more like that of adults

First author, Professor Giovanni Di Liberto, a cognitive and computer scientist at Trinity College Dublin and a researcher at the ADAPT Centre, said: “This is the first evidence we have of how brain activity relates to phonetic information changes over time in response to continuous speech.”

Previously, studies have relied on comparing the responses to nonsense syllables, like “bif” and “bof” instead.

The current study forms part of the BabyRhythm project led by Goswami, which is investigating how language is learnt and how this is related to dyslexia and developmental language disorder.

Goswami believes that it is rhythmic information – the stress or emphasis on different syllables of words and the rise and fall of tone – that is the key to language learning. A sister study, also part of the BabyRhythm project, has shown that rhythmic speech information was processed by babies at two months old – and individual differences predicted later language outcomes. The experiment was also conducted with adults who showed an identical ‘read out’ of rhythm and syllables to babies.

“We believe that speech rhythm information is the hidden glue underpinning the development of a well-functioning language system,” said Goswami. “Infants can use rhythmic information like a scaffold or skeleton to add phonetic information on to. For example, they might learn that the rhythm pattern of English words is typically strong-weak, as in ‘daddy’ or ‘mummy’, with the stress on the first syllable. They can use this rhythm pattern to guess where one word ends and another begins when listening to natural speech.”

“Parents should talk and sing to their babies as much as possible or use infant directed speech like nursery rhymes because it will make a difference to language outcome,” she added.

Goswami explained that rhythm is a universal aspect of every language all over the world. “In all language that babies are exposed to there is a strong beat structure with a strong syllable twice a second. We’re biologically programmed to emphasise this when speaking to babies.”

Goswami says that there is a long history in trying to explain dyslexia and developmental language disorder in terms of phonetic problems but that the evidence doesn’t add up. She believes that individual differences in children’s language originate with rhythm.

The research was funded by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and by Science Foundation Ireland.

ENDS.

Reference:

Di Liberto et al. Emergence of the cortical encoding of phonetic features in the first year of life, Nature Communications DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-43490-x

Contact details:

Charis Goodyear, University of Cambridge: Charis.Goodyear@admin.cam.ac.uk / researchcommunications@admin.cam.ac.uk

Professor Usha Goswami, University of Cambridge: ucg10@cam.ac.uk

Giovanni Di Liberto, Assistant Professor, Trinity College Dublin diliberg@tcd.ie

About the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is one of the world’s leading universities, with a rich history of radical thinking dating back to 1209. Its mission is to contribute to society through the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence.

Cambridge was second in the influential 2023 QS World University Rankings, the highest rated institution in the UK.

The University comprises 31 autonomous Colleges and over 100 departments, faculties and institutions. Its 20,000 students include around 9,000 international students from 147 countries. In 2022, 72.5% of its new undergraduate students were from state schools and more than 25% from economically disadvantaged backgrounds.

Cambridge research spans almost every discipline, from science, technology, engineering and medicine through to the arts, humanities and social sciences, with multi-disciplinary teams working to address major global challenges. In the Times Higher Education’s rankings based on the UK Research Excellence Framework, the University was rated as the highest scoring institution covering all the major disciplines.

The University sits at the heart of the ‘Cambridge cluster’, in which more than 5,200 knowledge-intensive firms employ more than 71,000 people and generate £19 billion in turnover. Cambridge has the highest number of patent applications per 100,000 residents in the UK.

www.cam.ac.uk

END

Why reading nursery rhymes and singing to babies may help them to learn language

Babies don’t begin to process phonetic information reliably until seven months old – which researchers say is too late to form the foundation of language

2023-12-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Brace for a potentially record-breaking winter after sweltering summer and autumn

2023-12-01

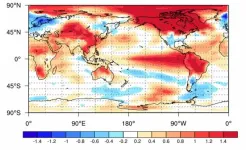

The scorching heatwaves of 2023's summer and autumn shook the world, raising a pertinent question: Will this lead into the warmest winter the globe has ever witnessed?

After a summer and autumn marked by extreme temperatures and a consistent global warming trend across oceans and landmasses, concerns mounted about what might follow. The global average temperature during June to October 2023 surpassed the 1991-2020 average by 0.57℃. August and September soared even higher, surpassing historical averages by 0.62℃ and 0.69℃, respectively, eclipsing the records set in 2016.

From hottest ...

Scientists raise alarm as bacteria are linked to mass death of sea sponges weakened by warming Mediterranean

2023-12-01

Vibrio bacteria, named for their vibrating swimming motion, span approximately 150 known species. Most Vibrio live in brackish or salt water, either swimming free or living as pathogens or symbionts in fish, crustaceans, molluscs, and corals. Because Vibrio thrive at relatively high temperatures, outbreaks in marine animals are expected to become ever more frequent under global warming. For example, over the past few decades, Vibrio have been implicated in the ‘bleaching’ of subtropical and tropical corals around the world.

Now, researchers from Spain and Turkey have shown that Vibrio bacteria also play a role in outbreaks of mortality of an unrelated ...

Mass General-developed brain care score (BCS) is a scientifically validated way to assess current health habits and risk to future brain health

2023-12-01

BOSTON – Individuals can improve their brain care and reduce their risk of developing brain diseases such as dementia and stroke by focusing on a list of 12 steps covering modifiable physical, lifestyle, and social-emotional components of health.

The list was developed and validated in research published in Frontiers in Neurology by investigators from the McCance Center for Brain Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and their collaborators in the United States and Europe.

For the study, the scientists ...

Exercise training improves obesity-related dementia

2023-12-01

Obesity is a major risk factor for cardiovascular metabolic diseases and neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia. Long-term exercise improves memory and spatial cognition, reduces age-related cognitive decline, and maintains brain volume, but the mechanisms are not fully understood.

Recently, a study from Febbraio lab at Monash University reported that voluntary exercise training (VET) improves long-term memory in high-fat diet (HFD)-induced obese mice, increases hippocampal neurogenesis ...

Paleolithic humans may have understood the properties of rocks for making stone tools

2023-12-01

A research group led by the Nagoya University Museum and Graduate School of Environmental Studies in Japan has clarified differences in the physical characteristics of rocks used by early humans during the Paleolithic. They found that humans selected rock for a variety of reasons and not just because of how easy it was to break off. This suggests that early humans had the technical skill to discern the best rock for the tool. The researchers published the results in the Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology.

As Homo sapiens moved from Africa to Eurasia, they used stone tools made of rocks, such as obsidian and flint, to cut, slice, and craft ranged weapons. Because ...

A patch of protection against Zika virus

2023-12-01

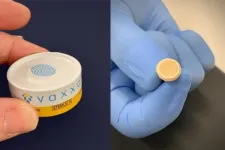

A simple-to-apply, needle-free vaccine patch is being developed to protect people from the potentially deadly mosquito-borne Zika virus.

A prototype using The University of Queensland-developed and Vaxxas-commercialised high-density microarray patch (HD-MAP) has delivered a University of Adelaide-developed vaccine and elicited an effective immune response to Zika virus in mice.

UQ alum and Vaxxas researcher Dr Danushka Wijesundara said Zika virus was a risk to people across the Pacific, Southeast Asia, India, Africa and South and Central America.

“We can change the way we combat Zika virus with the ...

ORNL supports executive order for safe, secure and trustworthy AI

2023-12-01

As artificial intelligence technologies improve, they increase the efficiency and capabilities of research across the scientific spectrum. Because of the rapid pace of the field, AI tools must be developed sustainably, a guiding principle for the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory throughout its 40 years of AI research. Now, its extensive array of resources are supporting the nation as it harnesses the power of these transformative technologies.

In October, President Biden ...

Photonic chip that ‘fits together like Lego’ opens door to semiconductor industry

2023-12-01

Researchers at the University of Sydney Nano Institute have invented a compact silicon semiconductor chip that integrates electronics with photonic, or light, components. The new technology significantly expands radio-frequency (RF) bandwidth and the ability to accurately control information flowing through the unit.

Expanded bandwidth means more information can flow through the chip and the inclusion of photonics allows for advanced filter controls, creating a versatile new semiconductor device.

Researchers expect the chip will have application in advanced radar, ...

Meteorites likely source of nitrogen for early Earth

2023-12-01

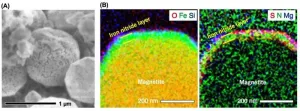

Micrometeorites originating from icy celestial bodies in the outer Solar System may be responsible for transporting nitrogen to the near-Earth region in the early days of our solar system. That discovery was published today in Nature Astronomy by an international team of researchers, including University of Hawai'i at Mānoa scientists, led by Kyoto University.

Nitrogen compounds, such as ammonium salts, are abundant in material born in regions far from the sun, but evidence of their transport to Earth's orbital region had been poorly understood.

"Our recent findings suggests the possibility that a greater amount of nitrogen compounds than previously ...

Can artificial intelligence improve life science? As much as life science can improve AI, researchers say

2023-12-01

Artificial intelligence (AI) may attempt to mimic the human brain, but it has yet to fully grasp the complexity of what it means to be human. While it may not truly understand feelings or original creativity, it can help us better understand ourselves — especially our physical bodies in health and in disease, according to a series of articles recently published by the journal Quantitative Biology.

The peer-reviewed papers — a variety of editorials, perspectives and commentaries on AI for life science — assess the rapid development of AI and recent attention ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Bison hunters abandoned long-used site 1,100 years ago to adapt to changing climate

Parents of children with medical complexity report major challenges with at-home medical devices

The nonlinear Hall effect induced by electrochemical intercalation in MoS2 thin flake devices

Moving beyond money to measure the true value of Earth science information

Engineered moths could replace mice in research into “one of the biggest threats to human health”

Can medical AI lie? Large study maps how LLMs handle health misinformation

The Lancet: People with obesity at 70% higher risk of serious infection with one in ten infectious disease deaths globally potentially linked to obesity, study suggests

Obesity linked to one in 10 infection deaths globally

Legalization of cannabis + retail sales linked to rise in its use and co-use of tobacco

Porpoises ‘buzz’ less when boats are nearby

When heat flows backwards: A neat solution for hydrodynamic heat transport

Firearm injury survivors face long-term health challenges

Columbia Engineering announces new program: Master of Science in Artificial Intelligence

Global collaboration launches streamlined-access to Shank3 cKO research model

Can the digital economy save our lungs and the planet?

Researchers use machine learning to design next generation cooling fluids for electronics and energy systems

Scientists propose new framework to track and manage hidden risks of industrial chemicals across their life cycle

Physicians are not providers: New ACP paper says names in health care have ethical significance

Breakthrough University of Cincinnati study sheds light on survival of new neurons in adult brain

UW researchers use satellite data to quantify methane loss in the stratosphere

Climate change could halve areas suitable for cattle, sheep and goat farming by 2100

Building blocks of life discovered in Bennu asteroid rewrite origin story

Engineered immune cells help reduce toxic proteins in the brain

Novel materials design approach achieves a giant cooling effect and excellent durability in magnetic refrigeration materials

PBM markets for Medicare Part D or Medicaid are highly concentrated in nearly every state

Baycrest study reveals how imagery styles shape pathways into STEM and why gender gaps persist

Decades later, brain training lowers dementia risk

Adrienne Sponberg named executive director of the Ecological Society of America

Cells in the ear that may be crucial for balance

Exploring why some children struggle to learn math

[Press-News.org] Why reading nursery rhymes and singing to babies may help them to learn languageBabies don’t begin to process phonetic information reliably until seven months old – which researchers say is too late to form the foundation of language