The ocean may be storing more carbon than estimated in earlier studies

2023-12-06

(Press-News.org)

The ocean's capacity to store atmospheric carbon dioxide is some 20% greater than the estimates contained in the latest IPCC report1. These are the findings of a study to be published in the journal Nature on December 6, 2023, led by an international team including a biologist from the CNRS2. The scientists looked at the role played by plankton in the natural transport of carbon from surface waters down to the seabed.

Plankton gobble up carbon dioxide and, as they grow, convert it into organic tissue via photosynthesis. When they die, part of the plankton is transformed into particles known as 'marine snow'. Being denser than seawater, these particles sink down to the seabed thus storing carbon there and providing essential nutrients for a wide range of deep-sea organisms, from tiny bacteria to deep-sea fish.

By analysing a bank of data collected from around the world by oceanographic vessels since the 1970s, the team of seven scientists were able to digitally map fluxes of organic matter throughout the world's oceans. The resulting new estimate of carbon storage capacity is 15 gigatonnes per year, an increase of around 20% compared with previous studies (11 gigatonnes per year) published by the IPCC in its 2021 report.

This reassessment of the ocean's storage capacity represents a significant advance in our understanding of carbon exchanges between the atmosphere and the ocean at the global level. While the team stresses that this absorption process takes place over tens of thousands of years, and is therefore not sufficient to offset the exponential increase in CO2 emissions caused by worldwide industrial activity since 1750, the study nonetheless highlights the importance of the ocean ecosystem as a major player in the long-term regulation of the global climate.

Notes

1 IPCC Climate Change 2021 Report, The Physical Science Basis, Chapter 5, Figure 5.12: Figure AR6 WG1 | Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (ipcc.ch)

2 From the Laboratoire des Sciences de l’Environnement Marin LEMAR (CNRS/UBO/IFREMER/IRD)

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2023-12-06

Researchers have discovered that misreading of therapeutic mRNAs by the cell’s decoding machinery can cause an unintended immune response in the body. They have identified the sequence within the mRNA that causes this to occur and found a way to prevent ‘off-target’ immune responses to enable the safer design of future mRNA therapeutics.

mRNA - or ‘messenger ribonucleic acid’ - is the genetic material that tells cells in the body how to make a specific protein. Researchers from the Medical Research Council (MRC) Toxicology Unit have discovered that the cellular ...

2023-12-06

Most neurodegenerative diseases, including dementias, involve proteins aggregating into filaments called amyloids. In most of these diseases, researchers have identified the proteins that aggregate, allowing them to target these proteins for diagnostic tests and treatments.

But, in around 10% of cases of frontotemporal dementia, scientists had yet to identify the rogue protein. Now, scientists have pinpointed aggregated structures of the protein TAF15 in these cases.

Frontotemporal dementia results from the degeneration of the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain, which control emotions, personality and behaviour, as well speech and understanding of words. ...

2023-12-06

Galactic winds enable the exchange of matter between galaxies and their surroundings. In this way, they limit the growth of galaxies, that is, their star formation rate. Although this had already been observed in the local universe, an international research team led by a CNRS scientist1 has just revealed—using MUSE,2 an instrument integrated into the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) Very Large Telescope—the existence of the phenomenon in galaxies which are more than 7 billion years old and actively forming stars, the category to which most galaxies belong. The team’s ...

2023-12-06

Brigham researchers found that individuals with darker skin tones and more severe acne were likely to face greater stigma

Researchers note the importance of treating acne as a medical problem and ensuring access to treatment

A new study highlights how stigmatizing attitudes about individuals with acne may influence social and professional perceptions. Led by investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, the study ...

2023-12-06

New York, NY (December 6, 2023)—Researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have identified an allergy pathway that, when blocked, unleashes antitumor immunity in mouse models of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

And in an early parallel study in humans, combining immunotherapy with dupilumab—an Interleukin-4 (IL-4) receptor-blocking antibody widely used for treating allergies and asthma—boosted patients' immune systems, with one out of the six experiencing significant tumor reduction.

The findings were ...

2023-12-06

About The Study: In this cross-sectional analysis of the U.S. adult population, 63% of adults had adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). The economic burden of ACE-related health conditions was substantial. The findings suggest that measuring the economic burden of ACEs can support decision-making about investing in strategies to improve population health.

Authors: Cora Peterson, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.46323)

Editor’s Note: Please ...

2023-12-06

About The Study: This survey study with 1,357 respondents demonstrates that stigmatizing attitudes toward patients with acne existed across a variety of social and professional scenarios, with severe acne and acne in darker skin tone being associated with a greater degree of stigma. These findings highlight the need to identify approaches to reduce stigmatizing attitudes in the community and for adequate access to care, which might prevent negative downstream effects related to these stigmatizing attitudes.

Authors: John ...

2023-12-06

About The Study: This randomized clinical trial found that a single health care worker-collected throat specimen had higher sensitivity for rapid antigen testing for SARS-CoV-2 than a nasal specimen. In contrast, the self-collected nasal specimens had higher sensitivity than throat specimens for symptomatic participants. Adding a throat specimen to the standard practice of collecting a single nasal specimen could improve sensitivity for rapid antigen testing in health care and home-based settings.

Authors: Tobias Todsen, M.D., Ph.D., of Copenhagen University Hospital in ...

2023-12-06

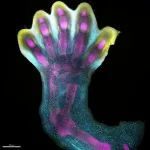

Human fingers and toes do not grow outward; instead, they form from within a larger foundational bud, as intervening cells recede to reveal the digits beneath. This is among many processes captured for the first time as scientists unveil a spatial cell atlas of the entire developing human limb, resolved in space and time.

Researchers at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, Sun Yat-sen University, EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute and collaborators applied cutting-edge single-cell and spatial technologies to create an atlas characterising the cellular landscape of the early human limb, pinpointing the exact ...

2023-12-06

Like any typical car or house or society, the pace at which parts of our bodies fall apart varies from part to part.

A study of 5,678 people, led by Stanford Medicine investigators, has shown that our organs age at different rates — and when an organ’s age is especially advanced in comparison with its counterpart in other people of the same age, the person carrying it is at heightened risk both for diseases associated with that organ and for dying.

According to the study, about 1 in every 5 reasonably ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] The ocean may be storing more carbon than estimated in earlier studies