(Press-News.org) A new paper in Genome Biology and Evolution, published by Oxford University Press, finds that genetic material from Neanderthal ancestors may have contributed to the propensity of some people today to be “early risers,” the sort of people who are more comfortable getting up and going to bed earlier.

All anatomically modern humans trace their origin to Africa around 300 thousand years ago, where environmental factors shaped many of their biological features. Approximately seventy-thousand years ago, the ancestors of modern Eurasian humans began to migrate out to Eurasia, where they encountered diverse new environments, including higher latitudes with greater seasonal variation in daylight and temperature.

But other hominins, such as the Neanderthals and Denisovans, had lived in Eurasia for more than 400,000 years. These archaic hominins diverged from modern humans around 700,000 ago, and as a result, our ancestors and archaic hominins evolved under different environmental conditions. This resulted in the accumulation of lineage-specific genetic variation and phenotypes. When humans came to Eurasia, they interbred with the archaic hominins on the continent, and this created the potential for humans to gain genetic variants already adapted to these new environments.

Previous work has demonstrated that much of the archaic hominin ancestry in modern humans was not beneficial and removed by natural selection, but some of the archaic hominin variants remaining in human populations show evidence of adaptation. For example, archaic genetic variants have been associated with differences in hemoglobin levels at higher altitude in Tibetans, immune resistance to new pathogens, levels of skin pigmentation, and fat composition.

Changes in the pattern and level of light exposure have biological and behavioral consequences that can lead to evolutionary adaptations. Scientists have previously explored the evolution of circadian adaptation in insects, plants, and fishes extensively, but it is not well studied in humans. The Eurasian environments where Neanderthals and Denisovans lived for several hundred thousand years are located at higher latitudes with more variable daylight times than the landscape where modern humans evolved before leaving Africa. Thus, the researchers explored whether there was genetic evidence for differences in the circadian clocks of Neanderthals and modern humans.

The researchers defined a set of 246 circadian genes through a combination of literature search and expert knowledge. They found hundreds of genetic variants specific to each lineage with the potential to influence genes involved in the circadian clock. Using artificial intelligence methods, they highlighted 28 circadian genes containing variants with potential to alter splicing in archaic humans and 16 circadian genes likely divergently regulated between present-day humans and archaic hominins. This indicated that there were likely functional differences between in the circadian clocks in archaic hominins and modern humans. Since the ancestors of Eurasian modern humans and Neanderthals interbred, it was thus possible that some humans could have obtained circadian variants from Neanderthals.

To test this, the researchers explored whether introgressed genetic variants—variants that moved from Neanderthals into modern humans—have associations with the preferences of the body for wakefulness and sleep in large cohort of several hundred thousand people from the UK Biobank. They found many introgressed variants with effects on sleep preference, and most strikingly, they found that these variants consistently increase morningness, the propensity to wake up early. This suggests a directional effect on the trait and is consistent with adaptations to high latitude observed in other animals.

Increased morningness in humans is associated with a shortened period of the circadian clock. This is likely beneficial at higher latitudes, because it has been shown to enable faster alignment of sleep/wake with external timing cues. Shortened circadian periods are required for synchronization to the extended summer light periods of high latitudes in fruit flies, and selection for shorter circadian periods has resulted in latitudinal clines of decreasing period with increasing latitude in natural fruit fly populations. Therefore, the bias toward morningness in introgressed variants may indicate selection toward shortened circadian period in the populations living at high latitudes. The propensity to be a morning person could have been evolutionarily beneficial for our ancestors living in higher latitudes in Europe and thus would have been a Neanderthal genetic characteristic worth preserving.

“By combining ancient DNA, large-scale genetic studies in modern humans, and artificial intelligence, we discovered substantial genetic differences in the circadian systems of Neanderthals and modern humans,” said the paper’s lead author, John A. Capra. “Then by analyzing the bits of Neanderthal DNA that remain in modern human genomes we discovered a striking trend: many of them have effects on the control of circadian genes in modern humans and these effects are predominantly in a consistent direction of increasing propensity to be a morning person. This change is consistent with the effects of living at higher latitudes on the circadian clocks of animals and likely enables more rapid alignment of the circadian clock with changing seasonal light patterns. Our next steps include applying these analyses to more diverse modern human populations, exploring the effects of the Neanderthal variants we identified on the circadian clock in model systems, and applying similar analyses to other potentially adaptive traits.”

The paper “Archaic Introgression Shaped Human Circadian Traits” is available (at midnight on December 14, 2023) at: https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evad203.

Direct correspondence to:

John A. Capra

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics

University of California, San Francisco

San Francisco, CA

tony@capralab.org

To request a copy of the study, please contact:

Daniel Luzer

daniel.luzer@oup.com

END

Were Neanderthals morning people ?

2023-12-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Mice with humanized immune systems to test cancer immunotherapies

2023-12-14

Mice with human immune cells are a new way of testing anti-cancer drugs targeting the immune system in pre-clinical studies. Using their new model, the Kobe University research team successfully tested a new therapeutic approach that blindfolds immune cells to the body’s self-recognition system and so makes them attack tumor cells.

Cancer cells display structures on their surface that identify them as part of the self and thus prevent them from being ingested by macrophages, a type of immune cell. Cancer immunotherapy aims at disrupting these recognition systems. Previous studies showed that a substance that blinds macrophages to one of ...

Quantum batteries break causality

2023-12-14

Batteries that exploit quantum phenomena to gain, distribute and store power promise to surpass the abilities and usefulness of conventional chemical batteries in certain low-power applications. For the first time, researchers including those from the University of Tokyo take advantage of an unintuitive quantum process that disregards the conventional notion of causality to improve the performance of so-called quantum batteries, bringing this future technology a little closer to reality.

When you hear the word “quantum,” the physics governing the subatomic world, developments in ...

Mothers and children have their birthday in the same month more often than you’d think – and here’s why

2023-12-14

Do you celebrate your birthday in the same month as your mum? If so, you are not alone. The phenomenon occurs more commonly than expected – a new study of millions of families has revealed.

Siblings also tend to share month of birth with each other, as do children and fathers, the analysis of 12 years’ worth of data shows, whilst parents are also born in the same month as one another more often than would be predicted.

Previous research has found that women’s season of ...

Bats declined as Britain felled trees for colonial shipbuilding

2023-12-14

Bat numbers declined as Britain’s trees were felled for shipbuilding in the early colonial period, new research shows.

The study, by the University of Exeter and the Bat Conservation Trust (BCT), found Britain’s Western barbastelle bat populations have dropped by 99% over several hundred years.

Animals’ DNA can be analysed to discover a “signature” of the past, including periods when populations declined, leading to more inbreeding and less genetic diversity.

Scientists used this method to discover the historic decline ...

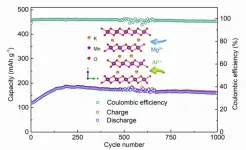

Guest pre-intercalation: an effective strategy to boost multivalent ion storage

2023-12-14

Due to the merits of low cost, low installation requirements, and high-level safety, aqueous rechargeable batteries (ARBs) offer an ideal option for dealing with future energy-demand pressure. Traditional aqueous batteries are mostly concentrated on mono-valent metal-ion, such as Li+, Na+, and K+. Compared to mono-valent carriers, multivalent cations have the capability to transfer more than one electron, and thereby to potentially provide better energy storage. To date, aqueous multivalent ion batteries based on Zn2+ have received a lot of attention. However, the investigations on aqueous ...

Unravelling the association between neonatal proteins and adult health

2023-12-14

Research led by Professor John McGrath from the University of Queensland found that the concentration of the C4 protein, an important part of the immune system, was not associated with risk of mental disorders.

However, the research also showed that a higher concentration of the C3 protein reduces the risk of schizophrenia in women, and studies based on the genetic correlates of C4 found strong links with several autoimmune disorders.

Professor John McGrath from UQ’s Queensland Brain Institute said his colleagues at Aarhus University in Denmark looked at ...

Gut bacteria of malnourished children benefit from key elements in therapeutic food

2023-12-14

A clinical trial reported in 2021 and conducted by a team of researchers from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research in Dhaka, Bangladesh, showed that a newly designed therapeutic food aimed at repairing malnourished children’s underdeveloped gut microbiomes was superior to a widely used standard therapeutic food.

Now, another study from the same research team at Washington University School of Medicine has identified key, naturally occurring biochemical components of this new therapeutic food and the important bacterial strains that process these ...

Gayle Benson makes historic donation for new home for Ochsner Children’s Hospital

2023-12-14

NEW ORLEANS, La. – Ochsner Health announces plans for The Gayle and Tom Benson Ochsner Children’s Hospital, made possible through a transformational gift from Mrs. Gayle Benson.

“We are proud to unveil much-anticipated plans for a new home for Louisiana’s No. 1 ranked children’s hospital,” said Pete November, CEO, Ochsner Health. “Ochsner is deeply grateful for Mrs. Benson and her unparalleled act of generosity, which will significantly impact the lives of countless families throughout Louisiana and the Gulf South. This facility will enable us to care for more children, retain and attract top pediatric physicians ...

Enzymes can’t tell artificial DNA from the real thing

2023-12-14

The genetic alphabet contains just four letters, referring to the four nucleotides, the biochemical building blocks that comprise all DNA. Scientists have long wondered whether it’s possible to add more letters to this alphabet by creating brand-new nucleotides in the lab, but the utility of this innovation depends on whether or not cells can actually recognize and use artificial nucleotides to make proteins.

Now, researchers at Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of California San Diego have ...

Decline in smoking in England has stalled since pandemic

2023-12-14

A decades-long decline in smoking prevalence in England has nearly ground to a halt since the start of the pandemic, according to a new study led by UCL researchers.

The study, funded by Cancer Research UK and published in the journal BMC Medicine, looked at survey responses from 101,960 adults between June 2017 and August 2022.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, from June 2017 to February 2020, smoking prevalence fell by 5.2% a year, but this rate of decline slowed to 0.3% during the pandemic (from April 2020 to August 2022), the study ...