(Press-News.org) Scientists have identified the protein that helps poison dart frogs safely accumulate their namesake toxins, according to a study published today in eLife.

The findings solve a long-standing scientific mystery and may suggest potential therapeutic strategies for treating humans poisoned with similar molecules.

Alkaloid compounds, such as caffeine, make coffee, tea and chocolate delicious and pleasant to consume, but can be harmful in large amounts. In humans, the liver can safely metabolise modest amounts of these compounds. Tiny poison dart frogs consume far more toxic alkaloids in their diets, but instead of breaking the toxins down, they accumulate them in their skin as a defence mechanism against predators.

“It has long been a mystery how poison dart frogs can transport highly toxic alkaloids around their bodies without poisoning themselves,” says lead author Aurora Alvarez-Buylla, a PhD student in the Biology Department at Stanford University in California, US. “We aimed to answer this question by looking for proteins that might bind and safely transport alkaloids in the blood of poison frogs.”

Alvarez-Buylla and her colleagues used a compound similar to the poison frog alkaloid as a kind of ‘molecular fishing hook’ to attract and bind proteins in blood samples taken from the Diablito poison frog. The alkaloid-like compound was bioengineered to glow under fluorescent light, allowing the team to see the proteins as they bound to this decoy.

Next, they separated the proteins to see how each one interacted with alkaloids in a solution. They discovered that a protein called alkaloid binding globulin (ABG) acts like a ‘toxin sponge’ that collects alkaloids. They also identified how the protein binds to alkaloids by systematically testing which parts of the protein were needed to bind it successfully.

“The way that ABG binds alkaloids has similarities to the way proteins that transport hormones in human blood bind their targets,” Alvarez-Buylla explains. “This discovery may suggest that the frog’s hormone-handling proteins have evolved the ability to manage alkaloid toxins.”

The authors say the similarities with human hormone-transporting proteins could provide a starting point for scientists to try and bioengineer human proteins that can ‘sponge up’ toxins. “If such efforts are successful, this could offer a new way to treat certain kinds of poisonings,” says senior author Lauren O’Connell, Assistant Professor in the Department of Biology, and a member of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, at Stanford University.

“Beyond potential medical relevance, we have achieved a molecular understanding of a fundamental part of poison frog biology, which will be important for future work on the biodiversity and evolution of chemical defences in nature,” O’Connell concludes.

##

Media contacts

Emily Packer, Media Relations Manager

eLife

e.packer@elifesciences.org

01223 855373

George Litchfield, Marketing and PR Assistant

eLife

g.litchfield@elifesciences.org

About eLife

eLife transforms research communication to create a future where a diverse, global community of scientists and researchers produces open and trusted results for the benefit of all. Independent, not-for-profit and supported by funders, we improve the way science is practised and shared. In support of our goal, we have launched a new publishing model that ends the accept/reject decision after peer review. Instead, papers invited for review will be published as a Reviewed Preprint that contains public peer reviews and an eLife assessment. We also continue to publish research that was accepted after peer review as part of our traditional process. eLife receives financial support and strategic guidance from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Max Planck Society and Wellcome. Learn more at https://elifesciences.org/about.

To read the latest Biochemistry and Chemical Biology research published in eLife, visit https://elifesciences.org/subjects/biochemistry-chemical-biology.

And for the latest in Ecology, see https://elifesciences.org/subjects/ecology.

END

Protein allows poison dart frogs to accumulate toxins safely

A newly identified protein helps poison dart frogs accumulate and store a potent toxin in their skin which they use for self-defence against predators

2023-12-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Toxic chemicals found in oil spills and wildfire smoke detected in killer whales

2023-12-19

Toxic chemicals produced from oil emissions and wildfire smoke have been found in muscle and liver samples from Southern Resident killer whales and Bigg’s killer whales.

A study published today in Scientific Reports is the first to find polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in orcas off the coast of B.C., as well as in utero transfer of the chemicals from mother to fetus.

“Killer whales are iconic in the Pacific Northwest—important culturally, economically, ecologically and more. Because they are able to metabolically process PAHs, these are most likely recent exposures. Orcas are our canary in the coal ...

Schar school researchers to receive funding for nonprofit employment data project

2023-12-19

Schar School Researchers To Receive Funding For Nonprofit Employment Data Project

Alan Abramson, Professor, Government and Politics; Mirae Kim, Associate Professor, Nonprofit Studies; and Stefan Toepler, Professor, Nonprofit Studies, are set to receive funding for: "Nonprofit Employment Data Project."

The researchers will produce a comprehensive report on nonprofit employment in the United States, based on new data that is expected to be released by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) early in 2024. The researchers will also arrange for the transfer of the Nonprofit Works interactive database application, which is currently hosted by Johns ...

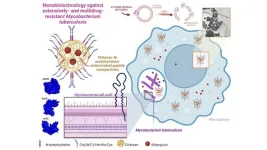

Nanoparticles with antibacterial action shorten duration of tuberculosis treatment

2023-12-19

A low-cost technology involving nanoparticles loaded with antibiotics and other antimicrobial compounds that can be used in multiple attacks on infections by the bacterium responsible for most cases of tuberculosis has been developed by researchers at São Paulo State University (UNESP) in Brazil and is reported in an article published in the journal Carbohydrate Polymers. Results of in vitro tests suggest it could be the basis for a treatment strategy to combat multidrug bacterial resistance.

According ...

Marzougui & Kan developing crashworthy tangent end treatment for low-speed & curbed roadways

2023-12-19

Marzougui & Kan Developing Crashworthy Tangent End Treatment For Low-Speed & Curbed Roadways

Dhafer Marzougui, Associate Professor, Physics and Astronomy, and Cing-Dao Kan, Professor/Director, Center for Collision Safety and Analysis, received $749,954 from the National Cooperative Highway Research Program for: "Development of a Crashworthy Tangent End Treatment for Low-Speed and Curbed Roadways."

This funding began in Nov. 2023 and will end in Nov. 2026.

###

About George Mason University

George Mason University is Virginia's largest public research university. ...

A malaria drug treatment could save babies’ lives

2023-12-19

Wars, drought, displacement, and instability are causing a dramatic increase in the number of pregnant and breastfeeding women around the world who suffer from malnutrition. Without access to sufficient nutrients in the womb, babies born to these women are more likely to die due to complications like pre-term birth, low birth weight, and susceptibility to diseases like malaria. To try to reduce the risk of malarial infection, the WHO recommends that pregnant women in low-income countries be treated with a combination of the antimalarial drugs sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine ...

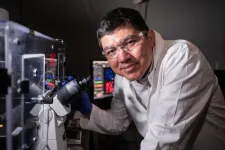

Engineered human heart tissue shows Stanford Medicine researchers the mechanics of tachycardia

2023-12-19

Heart rates are easier to monitor today than ever before. Thanks to smartwatches that can sense a pulse, all it takes is a quick flip of the wrist to check your heart. But monitoring the cells responsible for heart rate is much more challenging — and it’s encouraged researchers to invent new ways to analyze them.

Joseph Wu, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute and professor of medicine and of radiology, has devised a new stem cell-derived model of heart tissue ...

Molecular jackhammers’ ‘good vibrations’ eradicate cancer cells

2023-12-19

The Beach Boys’ iconic hit single “Good Vibrations” takes on a whole new layer of meaning thanks to a recent discovery by Rice University scientists and collaborators, who have uncovered a way to destroy cancer cells by using the ability of some molecules to vibrate strongly when stimulated by light.

The researchers found that the atoms of a small dye molecule used for medical imaging can vibrate in unison ⎯ forming what is known as a plasmon ⎯ when stimulated by near-infrared light, causing the cell membrane of cancerous cells to rupture. ...

Nearly 30% of caregivers for severe stroke survivors experience psychological distress

2023-12-19

Stroke is an abrupt, devastating disease that instantly changes a person’s life and has the potentially to cause lasting disability or death. However, the condition also has profound effects on the patient’s loved ones — who are often called to make difficult decisions quickly.

A new study led by Michigan Medicine finds that nearly 30% of caregivers of severe stroke patients experience high levels of anxiety, depression or post-traumatic stress during the first year after the patient leaves the hospital.

The results are published in Neurology.

“As physicians, we usually concentrate on our ...

MSU research suggests pandas are active posters on ‘social media’

2023-12-19

MSU has a satellite uplink/LTN TV studio and Comrex line for radio interviews upon request.

Images

Pandas, long portrayed as solitary creatures, do hang with family and friends — and they’re big users of “social media.” Scent-marking trees serve as a panda version of Facebook.

An article in the international journal Ursus paints a new lifestyle picture of the beloved bears in China’s Wolong National Nature Reserve, a life that’s shielded from human eyes because they’re shy, rare and live in densely forested, remote areas. No one really knows how pandas hang, but a new study indicates pandas are around others more than previously thought. ...

UTHSC, Vanderbilt University receive $2.4 million grant to promote diversity in speech-language pathologists for high-need children

2023-12-19

The Department of Audiology and Speech Pathology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center and the Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences at Vanderbilt University have secured a $2,399,454 grant to fund a five-year project to address the need for diversity in highly trained professionals in speech-language pathology.

The project, known as Project PAL (Preparing Academic Leaders in Speech-Language Pathology to Teach, Conduct Research, and Engage in Professional Service to Improve Outcomes for Children with High Need Communication Disorders), ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Bug beats: caterpillars use complex rhythms to communicate with ants

High-risk patients account for 80% of post-surgery deaths

Celebrity dolphin of Venice doesn’t need special protection – except from humans

Tulane study reveals key differences in long-term brain effects of COVID-19 and flu

The long standing commercialization challenge of lithium batteries, often called the dream battery, has been solved.

New method to remove toxic PFAS chemicals from water

The nanozymes hypothesis of the origin of life (on Earth) proposed

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

Researchers highlight promise of biochar composites for sustainable 3D printing

Machine learning helps design low-cost biochar to fight phosphorus pollution in lakes

Urine tests confirm alcohol consumption in wild African chimpanzees

Barshop Institute to receive up to $38 million from ARPA-H, anchoring UT San Antonio as a national leader in aging and healthy longevity science

Anion-cation synergistic additives solve the "performance triangle" problem in zinc-iodine batteries

Ancient diets reveal surprising survival strategies in prehistoric Poland

Pre-pregnancy parental overweight/obesity linked to next generation’s heightened fatty liver disease risk

Obstructive sleep apnoea may cost UK + US economies billions in lost productivity

Guidelines set new playbook for pediatric clinical trial reporting

Adolescent cannabis use may follow the same pattern as alcohol use

Lifespan-extending treatments increase variation in age at time of death

From ancient myths to ‘Indo-manga’: Artists in the Global South are reframing the comic

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

House fires release harmful compounds into the air

Novel structural insights into Phytophthora effectors challenge long-held assumptions in plant pathology

Q&A: Researchers discuss potential solutions for the feedback loop affecting scientific publishing

A new ecological model highlights how fluctuating environments push microbes to work together

Chapman University researcher warns of structural risks at Grand Renaissance Dam putting property and lives in danger

Courtship is complicated, even in fruit flies

Columbia announces ARPA-H contract to advance science of healthy aging

New NYUAD study reveals hidden stress facing coral reef fish in the Arabian Gulf

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

[Press-News.org] Protein allows poison dart frogs to accumulate toxins safelyA newly identified protein helps poison dart frogs accumulate and store a potent toxin in their skin which they use for self-defence against predators