(Press-News.org) After the last embers of a campfire dim, the musky smell of smoke remains. Whiffs of that distinct smokey smell may serve as a pleasant reminder of the evening prior, but in the wake of a wildfire, that smell comes with ongoing health risks.

Wildfire smoke is certainly more pervasive than a small campfire, and the remnants can linger for days, weeks and months inside homes and businesses. New research from Portland State’s Elliott Gall, associate professor in Mechanical and Materials Engineering, examined how long harmful chemicals found in wildfire smoke can persist and the most effective ways to remove them with everyday household cleaners.

Wildfires create compounds called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are formed in the combustion process at high temperatures. These compounds are highly toxic.

“They are associated with a wide variety of long-term adverse health consequences like cancer, potential complications in pregnancy and lung disease,” Gall said. “So if these compounds are depositing or sticking onto surfaces, there are different routes of exposure people should be aware of. By now, most people in Portland are probably thinking about how to clean their air during a wildfire smoke event, but they might not be thinking about other routes of exposure after the air clears.”

Public messaging is fairly consistent on what to do during a fire to reduce exposure to smoke — close windows and doors, run an air purifier and consider wearing a mask — but messaging is limited about what to do post-wildfire. Gall’s study published in Environmental Science & Technology looked at the accumulation and retention of PAHs over a period of four months on three different indoor materials: glass, cotton and air filters.

“We looked at a limited number of materials and we intentionally included some that are common in indoor environments,” Gall said.

Initial findings showed that levels of PAHs remained elevated for weeks after exposure. After materials were loaded with PAHs from wildfire smoke, it took 37 days for PAHs to decrease by 74% for air filters, 81% for cotton and 88% for glass. That reduction is significant but it takes time and means increased health risks from elongated exposure. However, laundering cotton materials just one time after exposure to smoke reduced PAHs on the material by 80%. Using a commercial glass cleaner on glass materials like windows and cups reduced PAHs between 60% and 70%.

Unlike glass and cotton, air filters can’t be cleaned and need to be replaced after an extreme smoke event.

“Even if there’s potentially some more life in them, over time PAHs can partition off the filter and be emitted back into your space,” Gall said. “While it may be a slow process, our study shows partitioning of PAHs from filters and other materials loaded with smoke may result in concentrations of concern in air. And while that partitioning is occurring, dermal contact and ingestion of PAHs from the materials may be important. One example might be holding and drinking from a glass that was exposed to wildfire smoke.”

Gall said it was important to consider the effect of cleaning solutions available to the average person. Although the findings also open the door to additional questions. How do materials like drywall or ceramic respond to cleaning, for example? What if an individual has access to a washer but not a dryer, would PAHs still be reduced to non-toxic levels?

The good news is that although toxic compounds after a wildfire can long outlast the palpable smoke, simple household cleaning techniques are effective in significantly reducing exposure. Gall said future studies on this subject will focus on additional surfaces common indoors and cleaning techniques to reduce PAHs, as well as work to understand the extent of possible health impacts from exposure.

END

Targeted household cleaning can reduce toxic chemicals post-wildfire, Portland State research shows

2024-01-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New method illuminates druggable sites on proteins

2024-01-02

LA JOLLA, CA—Identifying new ways to target proteins involved in human diseases is a priority for many researchers around the world. However, discovering how to alter the function of these proteins can be difficult, especially in live cells. Now, scientists from Scripps Research have developed a new method to examine how proteins interact with drug-like small molecules in human cells—revealing critical information about how to potentially target them therapeutically.

The strategy, published in Nature Chemical Biology on January 2, 2024, uses a combination of chemistry and analytical techniques to reveal the specific places where proteins and small molecules bind ...

RSV vaccines would greatly reduce illness if implemented like flu shots

2024-01-02

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines recently approved for people 60 and older would dramatically reduce the disease’s significant burden of illness and death in the United States if they were widely adopted like annual influenza vaccines, a new study has found.

A high level of RSV vaccination would not only potentially reduce millions of dollars in annual outpatient and hospitalization costs but would also produce an economy of scale with individual shots being delivered at a relatively modest cost of between $117 and $245 per dose, the study said.

The vaccines are currently covered by most private insurers without ...

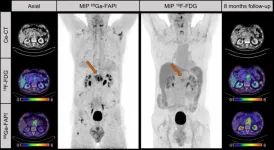

Ga-68 FAPI PET improves detection and staging of pancreatic cancer

2024-01-02

Reston, VA—PET imaging with 68Ga-FAPI can more effectively detect and stage pancreatic cancer as compared with 18F-FDG imaging or contrast-enhanced CT, according to new research published in the December issue of The Journal of Nuclear Medicine. In a head-to-head study, 68Ga-FAPI detected more pancreatic tumors on a per-lesion, per-patient, or per-region basis and led to major and minor changes to clinical management of patients. In addition to enhancing precise detection of pancreatic cancer, 68Ga-FAPI ...

Understanding climate mobilities: New study examines perspectives from South Florida practitioners

2024-01-02

Understanding Climate Mobilities: New study examines perspectives from South Florida practitioners

As climate change continues to impact people across South Florida, the need for adaptive responses becomes increasingly important.

A recent study led by researchers at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science, assessed the perspectives of 76 diverse South Florida climate adaptation professionals. The study titled, “Practitioner perspectives on climate mobilities in South Florida” was published in the December issue of the Journal Oxford Open Climate Change, and explores the expectations and concerns of practitioners from the ...

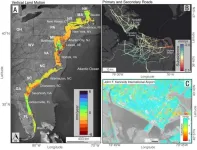

Study: From NYC to DC and beyond, cities on the East Coast are sinking

2024-01-02

Major cities on the U.S. Atlantic coast are sinking, in some cases as much as 5 millimeters per year – a decline at the ocean’s edge that well outpaces global sea level rise, confirms new research from Virginia Tech and the U.S. Geological Survey.

Particularly hard hit population centers such as New York City and Long Island, Baltimore, and Virginia Beach and Norfolk are seeing areas of rapid “subsidence,” or sinking land, alongside more slowly sinking or relatively stable ground, increasing the risk to roadways, runways, building foundations, rail ...

New PET tracer noninvasively identifies cancer gene mutation, allows for more precise diagnosis and therapy

2024-01-02

Reston, VA—A novel PET imaging tracer has been proven to safely and effectively detect a common cancer gene mutation that is an important molecular marker for tumor-targeted therapy. By identifying this mutation early, physicians can tailor treatment plans for patients to achieve the best results. This research was published in the December issue of The Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS) is a commonly mutated oncogene that is present in approximately 20-70 percent of cancer cases. Patients with KRAS mutations usually respond poorly to standard therapies. As such, the National Comprehensive ...

Evolution might stop humans from solving climate change, says new study

2024-01-02

Central features of human evolution may stop our species from resolving global environmental problems like climate change, says a new study led by the University of Maine.

Humans have come to dominate the planet with tools and systems to exploit natural resources that were refined over thousands of years through the process of cultural adaptation to the environment. University of Maine evolutionary biologist Tim Waring wanted to know how this process of cultural adaptation to the environment might influence the goal of solving global environmental problems. ...

January issues of APA journals cover antidepressant outcomes, disparities in school-based support, civil commitment hearings, and more

2024-01-02

WASHINGTON, D.C., Jan 2, 2024 — The latest issues of three American Psychiatric Association journals, The American Journal of Psychiatry, Psychiatric Services and The American Journal of Psychotherapy are now available online.

The January issue of The American Journal of Psychiatry features studies focusing on improving clinical outcomes and informing new interventions. Highlights include:

Predicting Acute Changes in Suicidal Ideation and Planning: A Longitudinal Study of Symptom Mediators and the Role of the Menstrual ...

Memory, brain function, and behavior: exploring the intricate connection through fear memories

2024-01-02

In a world grappling with the complexities of mental health conditions like anxiety, depression, and PTSD, new research from Boston University neuroscientist Dr. Steve Ramirez and collaborators offers a unique perspective. The study, recently published in the Journal of Neuroscience, delves into the intricate relationship between fear memories, brain function, and behavioral responses. Dr. Ramirez, along with his co-authors Kaitlyn Dorst, Ryan Senne, Anh Diep, Antje de Boer, Rebecca Suthard, Heloise ...

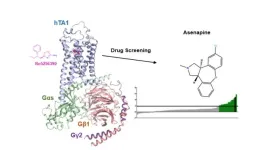

Demystifying a key receptor in substance use and neuropsychiatric disorders

2024-01-02

New York, NY (January 2, 2024)—Researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have uncovered insights into the potential mechanism of action of the antipsychotic medication asenapine, a possible therapeutic target for substance use and neuropsychiatric disorders. This discovery may pave the way for the development of improved medications targeting the same pathway.

Their findings, detailed in the January 2 online issue of Nature Communications https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44601-4, show that a brain protein known as the TAAR1 receptor, a drug target known to regulate dopamine signaling in key reward pathways in the brain, differs ...