(Press-News.org) Central features of human evolution may stop our species from resolving global environmental problems like climate change, says a new study led by the University of Maine.

Humans have come to dominate the planet with tools and systems to exploit natural resources that were refined over thousands of years through the process of cultural adaptation to the environment. University of Maine evolutionary biologist Tim Waring wanted to know how this process of cultural adaptation to the environment might influence the goal of solving global environmental problems. What he found was counterintuitive.

The project sought to understand three core questions: how human evolution has operated in the context of environmental resources, how human evolution has contributed to the multiple global environmental crises and how global environmental limits might change the outcomes of human evolution in the future.

Waring’s team outlined their findings in a new paper published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. Other authors of the study include Zach Wood, UMaine alumni, and Eörs Szathmáry, a professor at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, Hungary.

Human expansion

The study explored how human societies’ use of the environment changed over our evolutionary history. The research team investigated changes in the ecological niche of human populations, including factors such as the natural resources they used, how intensively they were used, what systems and methods emerged to use those resources and the environmental impacts that resulted from their usage.

This effort revealed a set of common patterns. Over the last 100,000 years, human groups have progressively used more types of resources, with more intensity, at greater scales and with greater environmental impacts. Those groups often then spread to new environments with new resources.

The global human expansion was facilitated by the process of cultural adaptation to the environment. This leads to the accumulation of adaptive cultural traits — social systems and technology to help exploit and control environmental resources such as agricultural practices, fishing methods, irrigation infrastructure, energy technology and social systems for managing each of these.

“Human evolution is mostly driven by cultural change, which is faster than genetic evolution. That greater speed of adaptation has made it possible for humans to colonize all habitable land worldwide,” says Waring, associate professor with the UMaine Senator George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions and the School of Economics.

Moreover, this process accelerates because of a positive feedback process: as groups get larger, they accumulate adaptive cultural traits more rapidly, which provides more resources and enables faster growth.

“For the last 100,000 years, this has been good news for our species as a whole.” Waring says, “but this expansion has depended on large amounts of available resources and space.”

Today, humans have also run out of space. We have reached the physical limits of the biosphere and laid claim to most of the resources it has to offer. Our expansion also is catching up with us. Our cultural adaptations, particularly the industrial use of fossil fuels, have created dangerous global environmental problems that jeopardize our safety and access to future resources.

Global limits

To see what these findings mean for solving global challenges like climate change, the research team looked at when and how sustainable human systems emerged in the past. Waring and his colleagues found two general patterns. First, sustainable systems tend to grow and spread only after groups have struggled or failed to maintain their resources in the first place. For example, the U.S. regulated industrial sulfur and nitrogen dioxide emissions in 1990, but only after we had determined that they caused acid rain and acidified many water bodies in the Northeast. This delayed action presents a major problem today as we threaten other global limits. For climate change, humans need to solve the problem before we cause a crash.

Second, researchers also found evidence that strong systems of environmental protection tend to address problems within existing societies, not between them. For example, managing regional water systems requires regional cooperation, regional infrastructure and technology, and these arise through regional cultural evolution. The presence of societies of the right scale is, therefore, a critical limiting factor.

Tackling the climate crisis effectively will probably require new worldwide regulatory, economic and social systems — ones that generate greater cooperation and authority than existing systems like the Paris Agreement. To establish and operate those systems, humans need a functional social system for the planet, which we don’t have.

“One problem is that we don’t have a coordinated global society which could implement these systems,” says Waring, “We only have sub-global groups, which probably won’t suffice. But you can imagine cooperative treaties to address these shared challenges. So, that’s the easy problem.”

The other problem is much worse, Waring says. In a world filled with sub-global groups, cultural evolution among these groups will tend to solve the wrong problems, benefitting the interests of nations and corporations and delaying action on shared priorities. Cultural evolution among groups would tend to exacerbate resource competition and could lead to direct conflict between groups and even global human dieback.

“This means global challenges like climate change are much harder to solve than previously considered,” says Waring. “It’s not just that they are the hardest thing our species has ever done. They absolutely are. The bigger problem is that central features in human evolution are likely working against our ability to solve them. To solve global collective challenges we have to swim upstream.”

Looking forward

Waring and his colleagues think that their analysis can help navigate the future of human evolution on a limited Earth. Their paper is the first to propose that human evolution may oppose the emergence of collective global problems and further research is needed to develop and test this theory.

Waring’s team proposes several applied research efforts to better understand the drivers of cultural evolution and search for ways to reduce global environmental competition, given how human evolution works. For example, research is needed to document the patterns and strength of human cultural evolution in the past and present. Studies could focus on the past processes that lead to the human domination of the biosphere, and on the ways cultural adaptation to the environment is occurring today.

But if the general outline proves to be correct, and human evolution tends to oppose collective solutions to global environmental problems, as the authors suggest, then some very pressing questions need to be answered. This includes whether we can use this knowledge to improve the global response to climate change.

“There is hope, of course, that humans may solve climate change. We have built cooperative governance before, although never like this: in a rush at a global scale.” Waring says.

The growth of international environmental policy provides some hope. Successful examples include the Montreal Protocol to limit ozone-depleting gasses, and the global moratorium on commercial whaling.

New efforts should include fostering more intentional, peaceful and ethical systems of mutual self-limitation, particularly through market regulations and enforceable treaties, that bind human groups across the planet together ever more tightly into a functional unit.

But that model may not work for climate change.

“Our paper explains why and how building cooperative governance at the global scale is different, and helps researchers and policymakers be more clear-headed about how to work toward global solutions,” says Waring.

This new research could lead to a novel policy mechanism to address the climate crisis: modifying the process of adaptive change among corporations and nations may be a powerful way to address global environmental risks.

As for whether humans can continue to survive on a limited planet, Waring says “we don’t have any solutions for this idea of a long-term evolutionary trap, as we barely understand the problem.” says Waring.

“If our conclusions are even close to being correct, we need to study this much more carefully,” he says.

END

Evolution might stop humans from solving climate change, says new study

2024-01-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

January issues of APA journals cover antidepressant outcomes, disparities in school-based support, civil commitment hearings, and more

2024-01-02

WASHINGTON, D.C., Jan 2, 2024 — The latest issues of three American Psychiatric Association journals, The American Journal of Psychiatry, Psychiatric Services and The American Journal of Psychotherapy are now available online.

The January issue of The American Journal of Psychiatry features studies focusing on improving clinical outcomes and informing new interventions. Highlights include:

Predicting Acute Changes in Suicidal Ideation and Planning: A Longitudinal Study of Symptom Mediators and the Role of the Menstrual ...

Memory, brain function, and behavior: exploring the intricate connection through fear memories

2024-01-02

In a world grappling with the complexities of mental health conditions like anxiety, depression, and PTSD, new research from Boston University neuroscientist Dr. Steve Ramirez and collaborators offers a unique perspective. The study, recently published in the Journal of Neuroscience, delves into the intricate relationship between fear memories, brain function, and behavioral responses. Dr. Ramirez, along with his co-authors Kaitlyn Dorst, Ryan Senne, Anh Diep, Antje de Boer, Rebecca Suthard, Heloise ...

Demystifying a key receptor in substance use and neuropsychiatric disorders

2024-01-02

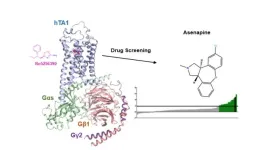

New York, NY (January 2, 2024)—Researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have uncovered insights into the potential mechanism of action of the antipsychotic medication asenapine, a possible therapeutic target for substance use and neuropsychiatric disorders. This discovery may pave the way for the development of improved medications targeting the same pathway.

Their findings, detailed in the January 2 online issue of Nature Communications https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44601-4, show that a brain protein known as the TAAR1 receptor, a drug target known to regulate dopamine signaling in key reward pathways in the brain, differs ...

Elusive cytonemes guide neural development, provide signaling ‘express route’

2024-01-02

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital scientists found that cytonemes (thin, long, hair-like projections on cells) are important during neural development. Cytonemes connect cells communicating across vast distances but are difficult to capture with microscopy in developing vertebrate tissues. The researchers are the first to find a way to visualize how cytonemes transport signaling molecules during mammalian nervous system development. The findings were published in Cell.

“We showed cytonemes are a direct express route for signal transport,” said corresponding author ...

Pioneering study indicates a potential treatment for corneal endothelial disease, reducing the need for corneal transplants

2024-01-02

Philadelphia, January 2, 2024 – Findings from a pioneering study in The American Journal of Pathology, published by Elsevier, reveal that administration of the neuropeptide α-melanocyte–stimulating hormone (α-MSH) promotes corneal healing and restores normal eye function to an otherwise degenerating and diseased cornea by providing protection against cell death and promoting cell regeneration.

Due to a lack of currently available medical therapy, patients suffering from corneal endothelial disease, ...

Diversity of bioluminescent beetles in Brazilian savanna has declined sharply in 30 years

2024-01-02

At night in the Cerrado, Brazil’s savanna and second-largest biome, larvae of the click beetle Pyrearinus termitilluminans, which live in termite mounds, display green lanterns to capture prey attracted by the bright light.

In more than 30 years of expeditions with his students to Emas National Park and farms around the conservation unit in Goiás state to collect specimens, the phenomenon has never been so rare, said Vadim Viviani, a professor at the Federal University of São Carlos’s Science and Technology for Sustainability Center (CCTS-UFSCar) in Sorocaba, São Paulo state.

“In the 1990s, we ...

Binghamton University professor and Nobel Laureate Stanley Whittingham wins 2023 VinFuture Grand Prize

2024-01-02

Binghamton University, State University of New York Distinguished Professor and Nobel Laureate M. Stanley Whittingham has been chosen as the joint winner of the $3 million 2023 VinFuture Grand Prize in recognition of his contributions to the invention of lithium-ion batteries. The prize recognized how the combination of solar energy and lithium battery storage is overcoming climate change and was recently presented by the Prime Minister of Vietnam.

“I am truly honored to be chosen for this prestigious honor,” said Whittingham. “VinFuture’s efforts to recognize green and sustainable energy is a noble cause, and ...

Deciphering molecular mysteries: new insights into metabolites that control aging and disease

2024-01-02

ITHACA, NY: In a significant advancement in the field of biochemistry, scientists at the Boyce Thompson Institute (BTI) and Cornell University have uncovered new insights into a family of metabolites, acylspermidines, that could change how we understand aging and fight diseases.

The study, recently published in Nature Chemical Biology, presents an unexpected connection between spermidine, a long-known compound present in all living cells, and sirtuins, an enzyme family that regulates many life-essential functions.

Sirtuins ...

Women’s and girls’ sports: more popular than you may think

2024-01-02

COLUMBUS, Ohio – The number of Americans who watch or follow girls’ and women’s sports goes well beyond those who view TV coverage of women’s athletic events, a new study suggests.

In fact, just over half of American adults spent some time watching or following female sports in the past year, the results showed.

U.S. adults spend about one hour a week consuming female sports content, which may seem higher than expected, according to the researchers. Still, it is only a small fraction of Americans’ overall sports consumption.

The study was ...

Calcium channel blockers key to reversing myotonic dystrophy muscle weakness, study finds

2024-01-02

New research has identified the specific biological mechanism behind the muscle dysfunction found in myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) and further shows that calcium channel blockers can reverse these symptoms in animal models of the disease. The researchers believe this class of drugs, widely used to treat a number of cardiovascular diseases, hold promise as a future treatment for DM1.

“The main finding of our study is that combined calcium and chloride channelopathy is highly deleterious and plays a central role in the function impairment of muscle found in the disease,” said John Lueck, Ph.D., an assistant professor at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) in the Departments ...