(Press-News.org) An atomic-level investigation of how Eastern equine encephalitis virus binds to a key receptor and gets inside of cells also has enabled the discovery of a decoy molecule that protects against the potentially deadly brain infection, in mice.

The study, from researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, is published Jan. 3 in the journal Cell. By advancing understanding of the complex molecular interactions between viral proteins and their receptors on animal cells, the findings lay a foundation for treatments and vaccines for viral infections.

“Understanding how viruses engage with the cells they infect is a critical part of preventing and treating viral disease,” said co-senior author Michael S. Diamond, MD, PhD, the Herbert S. Gasser Professor at Washington University. “Once you understand that, you have the foundation for developing vaccines and drugs to block it. In this study, it took us a long time to sort out the complexity associated with the particular receptor-virus interaction, but once we acquired this knowledge, we were able to design a decoy molecule that turned out to be very effective at neutralizing the virus and protecting mice from disease.”

Though infections of Eastern equine encephalitis virus in people are rare — with only a few cases reported worldwide each year — about one-third of those with the infection die, and many survivors suffer lasting neurological problems. Further, scientists predict that as the planet warms and climate change lengthens mosquito populations’ seasons and geographical reach, risk of infection will grow. At present, there are no approved vaccines against the virus or specific medications to treat it.

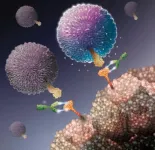

As a first step to finding ways to treat or prevent the deadly virus, Diamond and co-senior author Daved H. Fremont, PhD, a professor of pathology & immunology, set about investigating how the virus attaches to one of its key receptors — a molecule called VLDLR, or very low density lipoprotein receptor. The molecule is found on the surface of cells in the brain and other parts of the body. Co-first author Lucas Adams, an MD/PhD student in the Fremont and Diamond laboratories, used cryo-electron microscopy to reconstruct the virus binding to the receptor in atomic-level detail.

The results turned out to be unexpectedly complex. The molecule is composed of eight repeated segments, called domains, strung together like beads on a chain. Usually, a viral protein and its receptor fit together in one very specific way. In this case, however, two or three different spots on the viral surface proteins were capable of attaching to any of five of the molecule’s eight domains.

“What’s really striking is that we find multiple binding sites, but the chemistry of each of the binding sites is very similar and also similar to the chemistry of binding sites for other viruses that interact with related receptors,” said Fremont, who is also a professor of biochemistry & molecular biophysics and of molecular microbiology. “The chemistry just works out well for the way viruses want to attach to cell membranes.”

The domains that make up this molecule also are found in several related cell-surface proteins. Similar domains are found in proteins from across the animal kingdom.

“Since they’re using a molecule that naturally has repetitive domains, some of the alphaviruses have evolved to use the same strategy of attachment with multiple different domains in the same receptor,” said Diamond, who is also a professor of medicine, of molecular microbiology, and of pathology & immunology. Alphaviruses include Eastern equine encephalitis virus and several other viruses that cause brain or joint disease. “There are sequence differences in the VLDLR receptor over evolution in different species, but since the virus has this flexibility in binding, it is able to infect a wide variety of species including mosquitoes, birds, rodents and humans.”

To block attachment, the researchers created a panel of decoy receptors by combining subsets of the eight domains. The idea was that the virus mistakenly would bind to the decoy instead of the receptor on cells, and the decoy with the virus attached could then be cleared away by immune cells.

Co-first author Saravanan Raju, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the Diamond lab, evaluated the panel of decoys. First, he tested them on cells in dishes. Many neutralized the virus. Then, he turned to mice. Raju pretreated mice with a decoy or saline solution, as a control, six hours before injecting the virus under their skin, a mode of infection that mimics natural infection via mosquito bite. Three decoys were tested: one known to be unable to neutralize the virus; one made from the full-length molecule; and one made from just the first two domains.

All of the mice that received saline solution, the non-neutralizing decoy or the full-length decoy died within eight days of infection. All of the mice that received the decoy made from the first two domains survived without signs of illness.

Certain aspects of its biology give Eastern equine encephalitis virus the potential to be weaponized, making it particularly important to find a way to protect against it. In a subsequent experiment in which the mice were infected by inhalation — as would happen if the virus were aerosolized and used as a bioweapon — the decoy made from the first two domains was still effective, reducing the mice’s chance of death by 70%.

“Through a combination of the structural work and the domain deletion work, we were able to figure out which domains are the most critical and create a quite effective decoy receptor that can neutralize viral infection,” Fremont said. “This study broadens what we know about virus-receptor interactions and could lead to new approaches to preventing viral infections.”

END

Study reveals clues to how Eastern equine encephalitis virus invades brain cells

Structural biology research also enables scientists to design decoy molecule that blocks deadly infection

2024-01-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

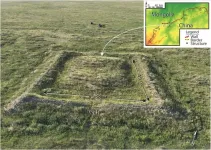

Unraveling the mysteries of the Mongolian Arc: exploring a monumental 405-kilometer wall system in Eastern Mongolia

2024-01-03

New study sheds light on the previously overlooked Mongolian Arc—a monumental wall system in eastern Mongolia spanning 405 kilometers. This discovery not only reveals the significance of this ancient architectural marvel but also prompts crucial questions about the motives, functionality, and broader implications of such colossal constructions. Their findings contribute to a larger multidisciplinary project exploring historical wall systems and their socio-political, economic, and environmental impacts, marking a pivotal milestone in understanding ancient civilizations and their enduring legacies.

[Jerusalem, ...

Call for EGU24 General Assembly Abstracts

2024-01-03

The General Assembly 2024 of the European Geosciences Union (EGU) will be held at the Austria Center Vienna (ACV) in Vienna, Austria and online, from 14–19 April 2024. eLTER will organise the following session:

BG8.14: Integrated solutions for landscape management of GHG balance and biodiversity in a changing environment

Convener: Syed Ashraful Alam, Katri Rankinen, Thomas Dirnböck, Harry Vereecken, Olga Vindušková

The session is co-sponsored by eLTER.

The abstract submission deadline is Wednesday, 10 January 2024, 13:00 CET.

Society is placing increasing and potentially competing demands on our environment. ...

Unlocking sustainable water treatment: the potential of piezoelectric-activated persulfate

2024-01-03

As cities grow bigger and faster, water pollution is becoming a serious problem. We need good ways to clean the water. Traditional cleaning methods, Persulfate (PS)- Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs), are good at treating the bad stuff in the water, but they require a lot of energy and chemicals, like special light and metals ions. This is costly and environmentally harmful. It's urgent to find better and more eco-friendly ways to clean it.

In a recent study published in Volume 18 of the journal Environmental Science and Ecotechnology, scientists ...

On-demand conformation of an artificial cytoskeleton

2024-01-03

Peptide nanotubes are tubular-shaped structures formed by the controlled stacking of cyclic peptide components. These hollow biomaterials show inner and outer faces, allowing the control over their properties.

Led by Juan R. Granja, researchers from the Center for Research in Biological Chemistry and Molecular Materials (CiQUS) presented a novel kind of cyclic peptide that, when light-irradiated, induces the formation or desegregation of nanotubes on demand. At the appropriate wavelength, the peptide switches from a folded to a flat conformation. When the planar conformation is ...

Can artificial intelligence (AI) improve musculoskeletal imaging?

2024-01-03

(Boston)—While musculoskeletal imaging volumes are increasing, there is a relative shortage of subspecialized musculoskeletal radiologists to interpret the studies. Is AI the solution?

“With the ongoing trend of increased imaging rates and decreased acquisition times, a variety of AI tools can support musculoskeletal radiologists by providing more optimized and efficient workflows,” says corresponding author Ali Guermazi, MD, PhD, chief of radiology at VA Boston Healthcare System and professor of radiology and medicine at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine.

In a new article in the journal Radiology, BU researchers provide ...

Case Western Reserve researchers land $1.125 million National Science Foundation grant to advance safer, faster and less expensive medical-imaging technology

2024-01-03

CLEVELAND—Diagnosing cancer today involves using chemical “contrast agents” to improve the accuracy of medical imaging processes such as X-rays as well as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans.

But those agents can be expensive, take more time to use and pose potential health concerns.

With a new four-year, $1.125 million grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF), researchers at Case Western Reserve University hope to develop an artificial intelligence (AI) alternative ...

PTSD: the brain basis of susceptibility - a free webinar from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation

2024-01-03

The Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (BBRF) is hosting a free webinar, “PTSD: The Brain Basis of Susceptibility” on Tuesday, January 9, 2024, at 2:00 pm ET. The presenter will be Nathaniel G. Harnett, Ph.D., Director of the NATE Lab at McLean Hospital and Assistant Professor in Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Harnett is also the recipient of a 2021 Young Investigator Grant. The webinar will be hosted by Jeffrey Borenstein, M.D., President & CEO of the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, and host of the public television series Healthy Minds.

Register today ...

Knowing how clinicians make real-world decisions about drug-drug interactions can improve patient safety

2024-01-03

INDIANAPOLIS — Drug-drug interactions causing adverse effects are common and can cause significant patient harm and even death. A new study is one of the first to examine how clinicians become aware of and process information about potential interactions and subsequently make their real-world decisions about prescribing. Based on these findings, the research team makes specific recommendations to aid clinician decision-making to improve patient safety.

“Drug-drug interactions are very common, more common than a lot of people outside the healthcare system expect. In the U.S., these interactions lead to hundreds of thousands of hospitalizations ...

Immune cell helps predict skin cancer patients’ chances of responding to treatment

2024-01-03

A type of immune cell can help predict which patients may benefit most from cancer immunotherapies, researchers from King’s College London, Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital Trust, and the Francis Crick Institute have found.

The study, published today in Nature Cancer, found that a rare type of T cells (a type of immune cell), can help predict the likelihood of whether a patient with advanced skin cancer will be responsive to immunotherapy treatments. The results could also lead to the development of new and more effective treatments for patients with melanoma who do not benefit from current ...

Reprogrammed fat cells support tumor growth

2024-01-03

Mutations of the tumor suppressor p53 not only have a growth-promoting effect on the cancer cells themselves, but also influence the cells in the tumor's microenvironment. Scientists at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the Weizmann Institute in Israel have now shown that p53-mutated mouse breast cancer cells reprogram fat cells. The manipulated fat cells create an inflammatory microenvironment, impairing the immune response against the tumor and thus promoting cancer growth.

No other gene is mutated as frequently in human tumors as the gene for the tumor suppressor p53. In around 30 percent of all cases of breast cancer, the cancer cells show mutations or losses ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

JBNU researchers review advances in pyrochlore oxide-based dielectric energy storage technology

Novel cellular phenomenon reveals how immune cells extract nuclear DNA from dying cells

Printable enzyme ink powers next-generation wearable biosensors

6 in 10 US women projected to have at least one type of cardiovascular disease by 2050

People’s gut bacteria worse in areas with higher social deprivation

Unique analysis shows air-con heat relief significantly worsens climate change

Keto diet may restore exercise benefits in people with high blood sugar

Manchester researchers challenge misleading language around plastic waste solutions

Vessel traffic alters behavior, stress and population trends of marine megafauna

Your car’s tire sensors could be used to track you

Research confirms that ocean warming causes an annual decline in fish biomass of up to 19.8%

Local water supply crucial to success of hydrogen initiative in Europe

New blood test score detects hidden alcohol-related liver disease

High risk of readmission and death among heart failure patients

Code for Earth launches 2026 climate and weather data challenges

Three women named Britain’s Brightest Young Scientists, each winning ‘unrestricted’ £100,000 Blavatnik Awards prize

Have abortion-related laws affected broader access to maternal health care?

Do muscles remember being weak?

Do certain circulating small non-coding RNAs affect longevity?

How well are international guidelines followed for certain medications for high-risk pregnancies?

New blood test signals who is most likely to live longer, study finds

Global gaps in use of two life-saving antenatal treatments for premature babies, reveals worldwide analysis

Bug beats: caterpillars use complex rhythms to communicate with ants

High-risk patients account for 80% of post-surgery deaths

Celebrity dolphin of Venice doesn’t need special protection – except from humans

Tulane study reveals key differences in long-term brain effects of COVID-19 and flu

The long standing commercialization challenge of lithium batteries, often called the dream battery, has been solved.

New method to remove toxic PFAS chemicals from water

The nanozymes hypothesis of the origin of life (on Earth) proposed

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

[Press-News.org] Study reveals clues to how Eastern equine encephalitis virus invades brain cellsStructural biology research also enables scientists to design decoy molecule that blocks deadly infection