(Press-News.org) Researchers have created a new brain imaging method that allows mild traumatic brain injuries (mTBIs) to be diagnosed, even when existing imaging techniques like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) don’t show any structural abnormalities. The technique involves loading gadolinium, a standard MRI contrast agent, into hydrogel-based micropatches that are attached to immune cells called macrophages. mTBIs cause inflammation in the brain, which produces signals that attract macrophages to migrate there. Coupling the gadolinium contrast agent to these cells enables MRI to reveal brain inflammation and increase the number of correctly diagnosed mTBI cases, improving patient care. The method is described in a new paper in Science Translational Medicine.

“70-90% of reported TBI cases are categorized as ‘mild,’ yet as many as 90% of mTBI cases go undiagnosed, even though their effects can last for years and they are known to increase the risk of a host of neurological disorders including depression, dementia, and Parkinson’s disease,” said senior author Samir Mitragotri, Ph.D., in whose lab the research was performed. “Our cell-based imaging approach exploits immune cells’ innate ability to travel into the brain in response to inflammation, enabling us to identify mTBIs that standard MRI imaging would miss.”

Mitragotri is a Core Faculty member of the Wyss Institute at Harvard University and the Hiller Professor of Bioengineering and Hansjörg Wyss Professor of Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard’s John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS).

Using immune cells to identify inflammation

Most of us know someone who has had a concussion (another name for an mTBI), sometimes even more than one. But the vast majority of people who experience an mTBI are never properly diagnosed. Without that diagnosis, they can exacerbate their injuries by returning to normal activity before they’re fully recovered, which can lead to further damage. Some studies even suggest that repeated mTBIs can lead to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), the neurodegenerative disease that has been found to afflict more than 90% of professional American football players.

Because the effects of mTBI are believed to be caused by “invisible” brain inflammation, members of the Mitragotri lab decided to leverage their experience with immune cells to create a better diagnostic. “Our previous projects have focused on controlling the behavior of immune cells or using them to deliver drugs to a specific tissue. We wanted to exploit another innate ability of immune cells - homing to sites of inflammation in the body - to carry imaging agents into the brain, where they can provide a visible detection signal for mTBI,” said first author Lily Li-Wen Wang, Ph.D.. Wang is a former Research Fellow in the Mitragotri Lab at the Wyss Institute and SEAS who is now a scientist at Landmark Bio.

The team planned to use their cellular backpack technology to attach gadolinium molecules to macrophages, a type of white blood cell that is known to infiltrate the brain in response to inflammation. But right away, they ran into a problem: in order to function as a contrast agent for MRI scans, gadolinium needs to interact with water. Their original backpack microparticles are compost of a polymer called PLGA, which is hydrophobic (meaning it repels water). So Wang and her co-authors started developing a new backpack made out of a hydrogel material that could be manufactured at a large scale in the lab.

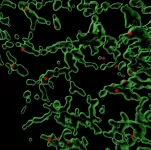

After years of hard work, they finally created a new hydrogel backpack that could produce a strong gadolinium-mediated MRI signal, attach stably to both mouse and pig macrophages, and maintain their cargo for a sustained period of time in vitro. They named their new microparticles M-GLAMs, short for “macrophage-hitchhiking Gd(III)-Loaded Anisotropic Micropatches.” Now, it was time to test them in a more realistic setting, for which they partnered with researchers and clinicians at Boston Children’s Hospital.

First, they injected mouse M-GLAMs macrophages into mice to see if they could visualize them in vivo. They were especially interested to see if they accumulated in the kidney, as existing gadolinium-based contrast agents like Gadavist® can cause health risks for patients with kidney disease. Their M-GLAMs did not accumulate in the mice’s kidneys, but persisted in their bodies for over 24 hours with no negative side effects. In contrast, mice injected with Gadavist® showed substantial accumulation of the contrast agent in their kidneys within 15 minutes of injection, and the substance was fully cleared from their bodies within 24 hours.

Then, they tested porcine M-GLAMs in a pig model of mTBI. They injected the M-GLAMs into the animals’ blood two days after a mock mTBI, then used MRI to evaluate the concentration of gadolinium in the brain. They focused on a small region called the choroid plexus, which is known as a major conduit of immune cells into the brain. Pigs that received the M-GLAMs displayed a significant increase in the intensity of gadolinium present in the choroid plexus, while those injected with Gadavist® did not, despite confirmation of increased inflammation macrophage density in the brains of both groups. The animals showed no toxicity in any of their major organs following administration of the treatments.

“Another important aspect of our M-GLAMs is that we are able to achieve better imaging at a much lower dose of gadolinium than current contrast agents - 500-1000-fold lower in the case of Gadavist®,” said Wang. “This could allow the use of MRI for patients who are currently unable to tolerate existing contrast agents, including those who have existing kidney problems.”

The authors note that while M-GLAMs can indicate the presence of inflammation in the brain via the high concentration of macrophages entering it through the choroid plexus, their technique cannot pinpoint the exact location of injuries or inflammatory responses in brain tissue. However, if coupled with new treatment modalities like one they developed in another recent paper[1] [王俐雯2] , M-GLAMS could offer a more rapid and effective way to identify and reduce inflammation in mTBI patients to minimize damage and speed their recovery.

The researchers have submitted a patent application for their technology, and hope to be able to bring it to the market in the near future. They are currently exploring collaborations with biotech and pharmaceutical companies to accelerate it to clinical trials[3] .

“This work demonstrates just how much potential is waiting to be unlocked within the human body for a variety of functions: monitoring health, diagnosing problems, treating diseases, and preventing their recurrence. I’m impressed with this team’s ingenuity in leveraging immune cells to improve medical imaging, and hope to see it in clinicians’ hands soon,” said Wyss Founding Director Donald Ingber, M.D., Ph.D. Ingber is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, and the Hansjörg Wyss Professor of Bioinspired Engineering at SEAS.

Additional authors of the paper include Yongsheng Gao, Vineeth Chandran Suja, Suyong Shaha, Rick Liao, Ninad Kumbhojkar, Supriya Prakash, Kyung Soo Park, and Michael Dunne from the Wyss Institute and SEAS; Masen Boucher, Kaitlyn Warren, Camilo Jaimes, and Rebekah Mannix from Boston Children’s Hospital; Neha Kapate and Morgan Janes from the Wyss Institute, SEAS, and MIT; Bolu Ilelaboye, Andrew Lu, and Solomina Darko from SEAS; and former SEAS members Tao Sun and John Clegg.

This research was supported by the US Department of Defense under Grant No. W81XWH-19-2-0011 and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant Nos. 1122374 and 1745302.

END

Shining a light on the hidden damage of mild brain injuries

Immune cell-based imaging method enables diagnosis of mild traumatic brain injuries (mTBI) that do not show up on MRIs

2024-01-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Weill Cornell Medicine receives grant for blood test to diagnose breast cancer

2024-01-03

Weill Cornell Medicine researchers received a $2.4 million grant from the U.S. Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program to validate a new blood test for the early detection of breast cancer.

Researchers are evaluating Syantra DX Breast Cancer (Syantra Inc.), an experimental diagnostic test that detects specific biomarkers in blood associated with breast cancer. The test uses an artificial intelligence algorithm to determine whether a patient is positive for cancer as soon as detectable by mammogram or possibly earlier, and before symptoms arise.

“This new liquid biopsy, ...

Using the body’s own cells to treat traumatic brain injury

2024-01-03

Scientists have created a new treatment for traumatic brain injury (TBI) that shrank brain lesions by 56% and significantly reduced local inflammation levels in pigs. The new approach leverages macrophages, a type of white blood cell that can dial inflammation up or down in the body in response to infection and injury. The team created disc-shaped microparticles called “backpacks” containing anti-inflammatory molecules, then attached them directly to the macrophages. These molecules kept the cells in an anti-inflammatory state ...

UW–Madison scientists reveal the inner workings of an essential protein trafficking complex

2024-01-03

MADISON – Like mail carriers who manage to deliver their parcels through snow, rain, heat and gloom, a critical group of mammalian proteins helps cells function properly even under less-than-ideal conditions.

Using state-of-the-art cell imaging and genome editing technology, University of Wisconsin–Madison scientists have begun to unravel how this collection of proteins performs its essential service. The discovery could eventually help researchers better understand and develop new treatments for diseases like cancer, diabetes and those that cause immune dysfunction.

Led by Anjon Audhya, a professor in the Department of Biomolecular Chemistry, the research team sought ...

Mapping of the gene network that regulates glycan clock of ageing

2024-01-03

“[...] we were able to confirm the functional role of three genes (MANBA, TNFRSF13B and EEF1A1) in the IgG galactosylation pathway [...]”

BUFFALO, NY- January 3, 2024 – A new research paper was published in Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science) Volume 15, Issue 24, entitled, “Mapping of the gene network that regulates glycan clock of ageing.”

Glycans are an essential structural component of immunoglobulin G (IgG) that modulate its structure and function. However, regulatory mechanisms behind this complex posttranslational ...

Computational method discovers hundreds of new ceramics for extreme environments

2024-01-03

DURHAM, N.C. – If you have a deep-seated, nagging worry over dropping your phone in molten lava, you’re in luck.

A research team led by materials scientists at Duke University has developed a method for rapidly discovering a new class of materials with heat and electronic tolerances so rugged that they that could enable devices to function at lava-like temperatures above several thousands of degrees Fahrenheit.

Harder than steel and stable in chemically corrosive environments, these materials ...

Community cancer care linked with poorer outcomes for patients with a common head and neck cancer

2024-01-03

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Care for patients with human papillomavirus (HPV)-related squamous cell cancers of the oropharynx (an area in back of the throat) is shifting toward community cancer centers, but patients treated in this setting may be less likely to survive, according to new research by investigators from the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and its Head and Neck Cancer Center.

The study, published Jan. 3 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, raises concerns about the quality of care that patients with this type of head and neck cancer receive outside of academic medical centers. Patients treated ...

Beta blocker used to treat heart problems and other medical concerns could be new treatment for sickle cell cardiomyopathy

2024-01-03

INDIANAPOLIS—A beta blocker typically used to treat heart problems, hemangioma, migraines and anxiety could be a new therapeutic for patients with sickle cell disease. Researchers led by Ankit A. Desai, MD, associate professor of medicine at the Krannert Cardiovascular Research Center (KCVRC) at Indiana University School of Medicine, have been awarded a $3 million grant by the U.S. Department of Defense to evaluate the efficacy of this drug.

Patients with sickle cell disease, a red blood ...

Cleveland Clinic and University of Western Ontario awarded $4.9 million from the Helmsley Charitable Trust to build Crohn’s disease and ileostomy research consortium

2024-01-03

Cleveland Clinic and the University of Western Ontario have been awarded a $4.9 million grant from Helmsley Charitable Trust to build a consortium to develop clinical trial outcome tools for patients with Crohn's disease and permanent ileostomy.

A permanent ileostomy is a surgical procedure to divert stool from the intestine after removing part of or the whole colon. The new Endpoint Development for Ostomy Clinical Trial (EndO-trial) Consortium seeks to develop more effective drugs for patients with Crohn's disease who have undergone ...

Researchers improve seed nitrogen content by reducing plant chlorophyll levels

2024-01-03

Chlorophyll plays a pivotal role in photosynthesis, which is why plants have evolved to have high chlorophyll levels in their leaves. However, making this pigment is expensive because plants invest a significant portion of the available nitrogen in both chlorophyll and the special proteins that bind it. As a result, nitrogen is unavailable for other processes. In a new study, researchers reduced the chlorophyll levels in leaves to see if the plant would invest the nitrogen saved into other process that might improve nutritional quality.

Over the past few decades, researchers ...

How does corrosion happen? New research examines process on atomic level

2024-01-03

BINGHAMTON, N.Y. -- When water vapor meets metal, the resulting corrosion can lead to mechanical problems that harm a machine’s performance. Through a process called passivation, it also can form a thin inert layer that acts as a barrier against further deterioration.

Either way, the exact chemical reaction is not well understood on an atomic level, but that is changing thanks to a technique called environmental transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which allows researchers to directly view molecules interacting ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Shining a light on the hidden damage of mild brain injuriesImmune cell-based imaging method enables diagnosis of mild traumatic brain injuries (mTBI) that do not show up on MRIs