(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON — Titan’s “magic islands” are likely floating chunks of porous, frozen organic solids, a new study finds, pivoting from previous work suggesting they were gas bubbles. The study was published in Geophysical Research Letters, AGU’s journal for high-impact, short-format reports with immediate implications spanning all Earth and space sciences.

A hazy orange atmosphere 50% thicker than Earth’s and rich in methane and other carbon-based, or organic, molecules blankets Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. Its surface is covered with dark dunes of organic material and seas of liquid methane and ethane. Stranger yet are what appear in radar imagery as shifting bright spots on the seas’ surfaces that can last a few hours to several weeks or more.

Scientists first spotted these ephemeral “magic islands” in 2014 with the Cassini-Huygens mission and have since been trying to figure out what they are. Previous studies suggested they could be phantom islands caused by waves or real islands made of suspended solids, floating solids, or bubbles of nitrogen gas. Xinting Yu, a planetary scientist and lead author of the new study, wondered if a closer look at the relationship between Titan’s atmosphere, liquid lakes, and the solid materials deposited on the moon’s surface could reveal the cause of these mysterious islands.

“I wanted to investigate whether the magic islands could actually be organics floating on the surface, like pumice that can float on water here on Earth before finally sinking,” Yu said.

A weird world of organics

Titan’s upper atmosphere is dense with diverse organic molecules. The molecules can clump together, freeze, and fall onto the moon’s surface — including onto its eerily smooth rivers and lakes of liquid methane and ethane, with waves only a few millimeters tall.

Yu and her team were interested in the fate of these organic clumps upon reaching Titan’s hydrocarbon lakes. Would they sink or float?

To find the answer, the team first investigated whether Titan’s organic solids would simply dissolve in the moon’s methane lakes. Because the lakes are already saturated with organic particles, the team determined that the falling solids would not dissolve when they reached the liquid.

“For us to see the magic islands, they can’t just float for a second and then sink,” Yu said. “They have to float for some time, but not for forever, either.”

Titan’s lakes and seas are primarily methane and ethane, both of which have low surface tension, making it harder for solids to float. The models suggested that most of the frozen solids were too dense and the surface tension too low to create Titan’s magic islands unless the clumps were porous like swiss cheese.

If the icy clumps were large enough and had the right ratio of holes and narrow tubes, the liquid methane could seep in slowly enough that the clumps could linger at the surface, the researchers found.

Yu’s modeling suggested individual clumps are likely too small to float by themselves. But if enough clumps massed together near the shore, larger pieces could break off and float away, similar to how glaciers calve on Earth. With a combination of a bigger size and the right porosity, these organic glaciers could explain the magic island phenomenon.

In addition to the magic islands, a thin layer of frozen solids coating Titan’s seas and lakes could explain the liquid bodies’ unusual smoothness. Thus, the findings from this study could explain two of Titan’s mysteries.

###

AGU (www.agu.org) is a global community supporting more than half a million advocates and professionals in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, AGU aims to advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

*****

Notes for Journalists: This study is published in Geophysical Research Letters, an open-access journal. Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo. View and download a pdf of the study here.

Paper title:

“The Fate of Simple Organics on Titan’s Surface”

Authors:

Xinting Yu (corresponding author), University of Texas at San Antonio

Yue Yu, University of California Santa Cruz, University of Geneva

Julia Garver, University of California Santa Cruz

Xi Zhang, University of California Santa Cruz

Patricia McGuiggan, Johns Hopkins University

Visit the AGU Newsroom to read about the latest science from AGU’s 24 journals, get updates about our organization, register for complimentary press access to AGU journals, and find topical experts. Visit eos.org to read Research Spotlights and Editors’ Highlights.

Update your subscription preferences.

END

Today, for the first time in human history, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities. Coincidentally, within the field of cultural heritage conservation, increasing international interest and attention over the past two decades has been focused on urban areas. This is timely because the pressure for economic development and for the prioritizing of engagement with the global economy have accompanied rapid urbanization. In many societies, economic development has privileged modernization efforts leading to the loss of traditional communities. ...

Irvine, Calif., Jan 4, 2024 — With a split-second muscle contraction, the greater blue-ringed octopus can change the size and color of the namesake patterns on its skin for purposes of deception, camouflage and signaling. Researchers at the University of California, Irvine have drawn inspiration from this natural wonder to develop a technological platform with similar capabilities for use in a variety of fields, including the military, medicine, robotics and sustainable energy.

According to its inventors, new devices made possible by this ...

Detecting malaria in people who aren’t experiencing symptoms is vital to public health efforts to better control this tropical disease in places where the mosquito-borne parasite is common. Asymptomatic people harboring the parasite can still transmit the disease or become ill later, after initially testing negative.

The dynamic lifecycle of this pathogen means that parasite densities can suddenly drop below the level of detection — especially when older, less sensitive tests are used. Such fluctuations can make it difficult, when testing only at a single point in time, to determine if an apparently healthy person is in fact infected.

Malaria ...

Under embargo until 00:01 GMT on Friday 5 January 2024 /19:01 ET Thursday 4 January 2024

Royal Astronomical Society and University of Oxford press release

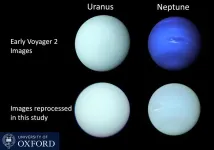

Neptune is fondly known for being a rich blue and Uranus green – but a new study has revealed that the two ice giants are actually far closer in colour than typically thought.

The correct shades of the planets have been confirmed with the help of research led by Professor Patrick Irwin from the University of Oxford, which has been published today in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

He and his team found that both worlds ...

Each summer, community college students from Colorado and surrounding states converge on the CU Boulder campus to participate in an immersive nine-week research program. A recent CIRES-led study reveals that when the students head home, they don’t just take new scientific and professional skills with them—they also leave with more confidence in their ability to do science and a greater sense of belonging in the science community. The work, published last month in PLOS ONE, suggests that authentic research experiences inspire community college students’ interest in STEM careers.

“Paid, ...

Having bipolar disorder – a serious mental illness that can cause both manic and depressed moods – can make life more challenging.

It also comes with a higher risk of dying early. Now, a study puts into perspective just how large that risk is, and how it compares with other factors that can shorten life.

In two different groups, people with bipolar disorder were four to six times more likely as people without the condition to die prematurely, the study finds.

By contrast, people who had ever smoked were about twice as likely to die prematurely than those ...

As if starting life with a potentially disabling genetic blood disease wasn’t enough, a study shows that almost two-thirds of babies born with sickle cell disease are born to mothers who live in disadvantaged areas.

But the study shows wide variation between states in the rate of births of babies with sickle cell to residents of areas with crowded housing, limited transportation options and other characteristics.

The researchers say their data could help public health authorities focus efforts to support the complex needs of children with sickle cell disease and their families.

The ...

A new study published in the journal Diabetes demonstrates that a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonist, a member of a class of medication used to treat Type 2 diabetes and obesity, can lead to a rapid improvement in insulin sensitivity.

Insulin sensitivity is how responsive cells are to insulin, an essential hormone that controls blood glucose levels. An increase in insulin sensitivity means insulin can more effectively lower the blood glucose. Reduced insulin sensitivity or insulin resistance is a feature of Type 2 diabetes. Thus, improved ...

A pair of proteins, YAP and TAZ, has been identified as conductors of bone development in the womb and could provide insight into genetic diseases such as osteogenesis imperfecta, known commonly as “brittle bone disease.” This small animal-based research, published today in Developmental Cell and led by members of the McKay Orthopaedic Research Laboratory of the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, adds understanding to the field of mechanobiology, which studies how mechanical forces influence biology.

“Despite more than a century of study on the mechanobiology of bone development, the cellular and molecular ...

Urbana, Ill. – When youth thrive despite difficult circumstances, they are usually lauded for their accomplishments. However, overcoming adversity may have a hidden physiological cost, especially for minority youth. A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign looks at physiological changes among high-striving minority youth in early adolescence.

“In the past decade, researchers have observed a phenomenon termed ‘skin-deep resilience.’ Historically, youth from disadvantaged backgrounds who ‘beat the odds’ were assumed to have universally positive outcomes. They are achieving academically, avoiding problematic behaviors, and scoring well on ...