(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. – Adults with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have smaller cerebellums, according to new research from a Duke-led brain imaging study.

The cerebellum, a part of the brain well known for helping to coordinate movement and balance, can influence emotion and memory, which are impacted by PTSD. What isn’t known yet is whether a smaller cerebellum predisposes a person to PTSD or PTSD shrinks the brain region.

“The differences were largely within the posterior lobe, where a lot of the more cognitive functions attributed to the cerebellum seem to localize, as well as the vermis, which is linked to a lot of emotional processing functions,” said Ashley Huggins, Ph.D., the lead author of the report who helped carry out the work as a postdoctoral researcher at Duke in the lab of psychiatrist Raj Morey, M.D.

Huggins, now an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Arizona, hopes these results encourage others to consider the cerebellum as an important medical target for those with PTSD.

“If we know what areas are implicated, then we can start to focus interventions like brain stimulation on the cerebellum and potentially improve treatment outcomes,” Huggins said.

The findings, published January 10 in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, have prompted Huggins and her lab to start looking for what comes first: a smaller cerebellum that might make people more susceptible to PTSD, or trauma-induced PTSD that leads to cerebellum shrinkage.

PTSD and the “Little Brain”

PTSD is a mental health disorder brought about by experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event, such as a car accident, sexual abuse, or military combat.

Though most people who endure a traumatic experience are spared from the disorder, about 6% of adults develop PTSD, which is often marked by increased fear and reliving the traumatizing event.

Researchers have found several brain regions involved in PTSD, including the almond-shaped amygdala that regulates fear, and the hippocampus, a critical hub for processing memories and routing them throughout the brain.

The cerebellum (Latin for “little brain”), by contrast, has received less attention for its role in PTSD.

A grapefruit-sized lump of cells that look like it was clumsily tacked underneath the back of the brain as an afterthought, the cerebellum is best known for its role in coordinating balance and choreographing complex movements, like walking or dancing. But there is much more to it than that.

“It's a really complex area,” Huggins said. “If you look at how densely populated with neurons it is relative to the rest of the brain, it's not that surprising that it does a lot more than balance and movement.”

Dense may be an understatement. The cerebellum makes up just 10% of the brain’s total volume but packs in more than half of the brain’s 86 billion nerve cells.

Researchers have recently observed changes to the size of the tightly-packed cerebellum in PTSD. Most of that research, however, is limited by either a small dataset (fewer than 100 participants), broad anatomical boundaries, or a sole focus on certain patient populations, such as veterans or sexual assault victims with PTSD.

Subtle and Consistent Reductions

To overcome those limitations, Duke’s Dr. Morey, along with over 40 other research groups that are part of a larger data-sharing initiative, pooled together their brain imaging scans to study PTSD as broadly and universally as possible.

The group ended up with images from 4,215 adult MRI scans, about a third of whom had been diagnosed with PTSD.

“I spent a lot of time looking at cerebellums,” Huggins said.

Even with automated software to analyze the thousands of brain scans, Huggins manually spot-checked every image to make sure the boundaries drawn around the cerebellum and its many subregions were accurate.

The result of this thorough methodology was a fairly simple and consistent finding: PTSD patients had cerebellums about 2% smaller.

When Huggins zoomed in to specific areas within the cerebellum that influence emotion and memory, she found similar cerebellar reductions in people with PTSD.

Huggins also discovered that the worse PTSD was for a person, the smaller their cerebellum was.

“Focusing purely on a yes-or-no categorical diagnosis doesn't always give us the clearest picture,” Huggins said. “When we looked at PTSD severity, people who had more severe forms of the disorder had an even smaller cerebellar volume.”

Targeting the Cerebellum for Treatment and More Research

The results are an important first step at looking at how and where PTSD affects the brain.

There are more than 600,000 combinations of symptoms that can lead to a PTSD diagnosis, Huggins explained. Figuring out if different PTSD symptom combinations have different impacts on the brain will also be important to keep in mind.

For now, though, Huggins hopes this work helps others recognize the cerebellum as an important driver of complex behavior and processes beyond gait and balance, as well as a potential target for new and current treatments for people with PTSD.

“While there are good treatments that work for people with PTSD, we know they don't work for everyone,” Huggins said. “If we can better understand what's going on in the brain, then we can try to incorporate that information to come up with more effective treatments that are longer lasting and work for more people.”

For details on funding and conflict disclosures, please see the preprint of the manuscript on bioRxiv.

CITATION: “Smaller Total And Subregional Cerebellar Volumes In Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Mega-Analysis By The ENIGMA-PGC PTSD Workgroup,” Ashley A. Huggins, C. Lexi Baird, Melvin Briggs, et al. Molecular Psychiatry, January 10, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41380-023-02352-0

END

Traumatic stress associated with smaller brain region

People with PTSD have a cerebellum about 2% smaller than unaffected adults, especially in areas that influence emotion and memory

2024-01-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

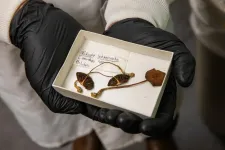

Largest diversity study of ‘magic mushrooms’ investigates the evolution of psychoactive psilocybin production

2024-01-10

Psilocybe fungi, known colloquially as “magic mushrooms,” have held deep significance in Indigenous cultures of Mesoamerica for centuries. They captured the wider world’s attention as a psychedelic staple in the 60s and 70s. Now, these infamous organisms are at the forefront of a mental health revolution. Psilocybin and psilocin, the psychoactive compounds found in nearly all species of Psilocybe, have shown promise as a treatment for conditions including PTSD, depression, and for easing end-of-life care.

To ...

Sex-specific panel of 10 proteins can pick up 18 different early stage cancers

2024-01-10

A sex-specific panel of 10 proteins can pick up 18 different early stage cancers, representing all the major organs of the human body, finds a proof of concept study published in the open access journal BMJ Oncology.

The findings could kick-start a new generation of screening tests for early detection of the disease, say the researchers, particularly as there are many sex specific differences in cancer—including age at occurrence, cancer types, and genetic alterations—points out a linked editorial.

Cancer accounts for 1 in every 6 deaths around the globe, with nearly 60% of these deaths ...

Predominantly plant-based or vegetarian diet linked to 39% lower odds of COVID-19

2024-01-10

A predominantly plant-based or vegetarian diet is linked to 39% lower odds of COVID-19 infection, finds research published in the open access journal BMJ Nutrition Prevention & Health.

The findings prompt the researchers to suggest that a diet high in vegetables, legumes, and nuts, and low in dairy products and meat may help to ward off the infection.

Several studies have suggested that diet may have an important role in the evolution of COVID-19 infection, as well as in the factors that heighten the risk of its associated ...

Early menopause and HRT among hormonal factors linked to heightened rheumatoid arthritis risk

2024-01-10

Early menopause—before the age of 45—taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and having 4 or more children are among several hormonal and reproductive factors linked to a heightened risk of rheumatoid arthritis in women, finds a large long term study published in the open access journal RMD Open.

Women are more susceptible to this autoimmune disease than men, note the researchers. They are 4–5 times as likely as men to develop rheumatoid arthritis under the age of 50, and twice as likely to do so between the ages of 60 and 70. And the disease seems to take a greater physical toll on women than it does on men.

While ...

City of Hope Children’s Cancer Center, Children’s Oncology Group conduct largest clinical trial seeking to prevent heart failure among childhood cancer survivors

2024-01-10

LOS ANGELES — Physicians at City of Hope, one of the largest cancer research and treatment organizations in the United States, in cooperation with the Children’s Oncology Group (COG), have conducted the largest clinical trial to date seeking to reduce the risk of people who have survived childhood cancer from developing heart failure. The findings published in The Lancet Oncology show that the blood vessel relaxing medication carvedilol is safe for childhood cancer survivors to take and may improve important markers of heart injury sustained as a result of chemotherapy exposure.

One devastating ...

New research sheds light on an old fossil solving an evolutionary mystery

2024-01-10

New York, January 9, 2024 — A research paper published in Royal Society’s Biology Letters on January 10 has revealed that picrodontids —an extinct family of placental mammals that lived several million years after the extinction of the dinosaurs—are not primates as previously believed.

The paper—co-authored by Jordan Crowell, an Anthropology Ph.D. candidate at the CUNY Graduate Center; Stephen Chester, an Associate Professor of Anthropology at Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center; ...

No laughing matter: Leadership critical to help address NHS retention crisis

2024-01-10

Frontline healthcare workers in busy hospitals feel that they are “just rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic” according to new research into the impact of under-resourced and high-pressure emergency hospital departments in the UK.

A study from the Royal College of Emergency Medicine and University of Bath, led by clinical psychologist Dr Jo Daniels in collaboration with colleagues at UWE Bristol and the University of Bristol, argues that hospitals need better leadership to help change cultures and support people’s basic needs.

In addition to reflections ...

Acidity of Antarctic waters could double by century’s end, threatening biodiversity

2024-01-10

The acidity of Antarctica’s coastal waters could double by the end of the century, threatening whales, penguins and hundreds of other species that inhabit the Southern Ocean, according to new research from the Univeristy of Colorado Boulder.

Scientists projected that by 2100, the upper 650 feet (200 meters) of the ocean—where much marine life resides—could see more than a 100% increase in acidity compared with 1990s levels. The paper, appeared Jan. 4 in the journal Nature Communications.

“The findings are critical for our understanding ...

Injectable hydrogel electrodes open door to a novel painless treatment regimen for arrhythmia

2024-01-09

HOUSTON (Jan 9, 2024)— A breakthrough study led by Dr. Mehdi Razavi at The Texas Heart Institute (THI), in collaboration with a biomedical engineering team of The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin) Cockrell School of Engineering led by Dr. Elizabeth Cosgriff-Hernandez, sets the foundation of a ground-breaking treatment regimen for treating ventricular arrhythmia. Their study published in Nature Communications demonstrates the design and feasibility of a new hydrogel-based pacing modality.

The urgent need for an effective therapeutic ...

Inspired by Greek mythology, this potential drug shows promise for vanquishing Parkinson’s RNA in early studies

2024-01-09

JUPITER, Fla. — Like the Greek mythological beast with a snake’s tail and two ferocious heads, a potential Parkinson’s medicine created in the lab of chemist Matthew Disney, Ph.D., is also a type of chimera bearing two heads. One seeks out a key piece of Parkinson’s-causing RNA, while the other goads the cell to chop it to pieces for recycling.

The research is described in the Jan. 9 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, or PNAS.

Parkinson’s is a frustrating and all too common disease. Slowly, people with Parkinson’s lose brain cells and other neurons needed to make the neurotransmitter dopamine. This progressive ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

[Press-News.org] Traumatic stress associated with smaller brain regionPeople with PTSD have a cerebellum about 2% smaller than unaffected adults, especially in areas that influence emotion and memory