(Press-News.org) Scientists have found the strongest evidence yet that our brains can compensate for age-related deterioration by recruiting other areas to help with brain function and maintain cognitive performance.

As we age, our brain gradually atrophies, losing nerve cells and connections and this can lead to a decline in brain function. It’s not fully understood why some people appear to maintain better brain function than others, and how we can protect ourselves from cognitive decline.

A widely accepted notion is that some people’s brains are able to compensate for the deterioration in brain tissue by recruiting other areas of the brain to help perform tasks. While brain imaging studies have shown that the brain does recruit other areas, until now it has not been clear whether this makes any difference to performance on a task, or whether it provides any additional information about how to perform that task.

In a study published in the journal eLife, a team led by scientists at the University of Cambridge in collaboration with the University of Sussex have shown that when the brain recruits other areas, it improves performance specifically in the brains of older people.

Study lead Dr Kamen Tsvetanov, an Alzheimer's Society Dementia Research Leader Fellow in the Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, said: “Our ability to solve abstract problems is a sign of so-called ‘fluid intelligence’, but as we get older, this ability begins to show significant decline. Some people manage to maintain this ability better than others. We wanted to ask why that was the case – are they able to recruit other areas of the brain to overcome changes in the brain that would otherwise be detrimental?”

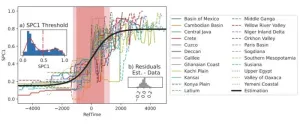

Brain imaging studies have shown that fluid intelligence tasks engage the ‘multiple demand network’ (MDN), a brain network involving regions both at the front and rear of the brain, but its activity decreases with age. To see whether the brain compensated for this decrease in activity, the Cambridge team looked at imaging data from 223 adults between 19 and 87 years of age who had been recruited by the Cambridge Centre for Ageing & Neuroscience (Cam-CAN).

The volunteers were asked to identify the odd-one-out in a series of puzzles of varying difficulty while lying in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner, so that the researchers could look at patterns of brain activity by measuring changes in blood flow.

As anticipated, in general the ability to solve the problems decreased with age. The MDN was particularly active, as were regions of the brain involved in processing visual information.

When the team analysed the images further using machine-learning, they found two areas of the brain that showed greater activity in the brains of older people, and also correlated with better performance on the task. These areas were the cuneus, at the rear of the brain, and a region in the frontal cortex. But of the two, only activity in the cuneus region was related to performance of the task more strongly in the older than younger volunteers, and contained extra information about the task beyond the MDN.

Although it is not clear exactly why the cuneus should be recruited for this task, the researchers point out that this brain region is usually good at helping us stay focused on what we see. Older adults often have a harder time briefly remembering information that they have just seen, like the complex puzzle pieces used in the task. The increased activity in the cuneus might reflect a change in how often older adults look at these pieces, as a strategy to make up for their poorer visual memory.

Dr Ethan Knights from the Medical Research Council Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit at Cambridge said: “Now that we’ve seen this compensation happening, we can start to ask questions about why it happens for some older people, but not others, and in some tasks, but not others. Is there something special about these people – their education or lifestyle, for example – and if so, is there a way we can intervene to help others see similar benefits?”

Dr Alexa Morcom from the University of Sussex’s School of Psychology and Sussex Neuroscience research centre said: “This new finding also hints that compensation in later life does not rely on the multiple demand network as previously assumed, but recruits areas whose function is preserved in ageing.”

The research was supported by the Medical Research Council, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, the Guarantors of Brain, and the Alzheimer’s Society.

Reference

Knights, E. et al. Neural Evidence of Functional Compensation for Fluid Intelligence Decline in Healthy Ageing. eLife; 6 Feb 2024; DOI: 10.7554/eLife.9332

END

Study finds strongest evidence to date of brain’s ability to compensate for age-related cognitive decline

2024-02-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How T cells combat tuberculosis

2024-02-06

LA JOLLA, CA—La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) is working to guide the development of new tuberculosis vaccines and drug therapies.

Now a team of LJI scientists has uncovered important clues to how human T cells combat Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes TB. Their findings were published recently in Nature Communications.

"This research gives us a better understanding of T cell responses to different stages in tuberculosis infection and helps us figure out is there are additional diagnostic ...

Drug could protect brains from damage after concussions

2024-02-06

Repeat concussions, also referred to as repetitive mild traumatic brain injury, can lead to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and raise the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. However, some people who experience repetitive mild traumatic brain injury never develop major disease. Onder Albayram and colleagues investigated the role of a protein known as p17 in protecting brains from long-term pathologies. In stressed neurons, p17 initiates production of C18-Ceramide, a bioactive sphingolipid that acts as a label of damaged mitochondria in neuronal axons. Labelled mitochondria are then detected and removed by autophagosomes. The authors knocked out p17 in mice. Some p17-knockout ...

Is there a typical rate of cultural evolution?

2024-02-06

Are cultural evolution rates similar across human societies? The emerging field of Cliodynamics uses mathematical models to study history. Tobias Wand and colleagues used a data-driven approach to estimate the rates of cultural evolution in 23 geographic areas, using data from Seshat: Global History Databank, which records nine “complexity characteristics” for 370 polities over 10,000 years, ending in the nineteenth century. The complexity characteristics are polity population; extent of polity territory; the size of the largest urban center; hierarchical complexity; the ...

Last chance to get hotel discounts for the world’s largest physics meeting

2024-02-06

Next month, scientists from around the world will convene to share new results from across the physical sciences in nearly 11,000 individual presentations. The American Physical Society’s (APS) March Meeting will be held in person in Minneapolis and online everywhere March 3-8.

Discounted hotel rates are available for in-person attendees at select Minneapolis hotels near the Minneapolis Convention Center. Book your hotel by Feb. 9 to receive the discount.

Press Registration

News media with valid APS press credentials may register for the meeting at no cost. To request press credentials, visit APS’s online newsroom. Registration ...

Newly discovered carbon monoxide-runaway gap can help identify habitable exoplanets

2024-02-06

The search for habitable exoplanets involves looking for planets with similar conditions to the Earth, such as liquid water, a suitable temperature range and atmospheric conditions. One crucial factor is the planet's position in the habitable zone, the region around a star where liquid water could potentially exist on the planet's surface. NASA's Kepler telescope, launched in 2009, revealed that 20–50% of visible stars may host such habitable Earth-sized rocky planets. However, the presence of liquid water alone does not guarantee a planet’s habitability. On Earth, ...

Pore power: high-speed droplet production in microfluidic devices

2024-02-06

Over the past two decades, microfluidic devices, which use technology to produce micrometer-sized droplets, have become crucial to various applications. These span chemical reactions, biomolecular analysis, soft-matter chemistry, and the production of fine materials. Furthermore, droplet microfluidics has enabled new applications that were not possible with traditional methods. It can shape the size of the particles and influence their morphology and anisotropy. However, the conventional way of generating droplets in a single microchannel structure is often slow, ...

How a city is organized can create less-biased citizens

2024-02-06

The city you live in could be making you, your family, and your friends more unconsciously racist. Or, your city might make you less racist. It depends on how populous, diverse, and segregated your city is, according to a new study that brings together the math of cities with the psychology of how individuals develop unconscious racial biases.

The study, published in the latest issue of Nature Communications, presents data and a mathematical model of exposure and adaptation in social networks that can help explain why there is more unconscious, or implicit, racial bias ...

Reversible deformation, permanent fabric development

2024-02-06

6 February 2024

The Geological Society of America

Release No. 24-01

Contributed by Arianna Soldati, GSA Science Communication Fellow

Boulder, Colo., USA: Earth is a stressed planet. As plates move, magma rises, and glaciers melt—just to mention a few scenarios—rocks are subject to varying pressure and compressional and extensional forces. The effect of these stresses on rock mineralogy and texture is of great interest to the tectono-metamorphic community. Yet the link between process and outcome remains elusive.

There are two possible states of stress: either all principal ...

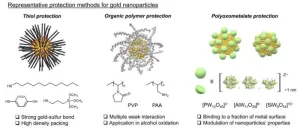

Researchers strike gold with improved catalyst

2024-02-06

For the first time, researchers including those at the University of Tokyo discovered a way to improve the durability of gold catalysts by creating a protective layer of metal oxide clusters. The enhanced gold catalysts can withstand a greater range of physical environments compared to unprotected equivalent materials. This could increase their range of possible applications, as well as reduce energy consumption and costs in some situations. These catalysts are widely used throughout industrial settings, including chemical synthesis and production of medicines, these industries could benefit from improved gold catalysts.

Everybody loves gold: athletes, pirates, bankers — everybody. ...

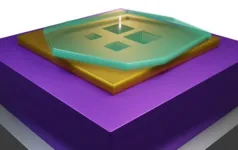

Breaking boundaries in quantum photonics: Groundbreaking nanocavities unlock new frontiers in light confinement

2024-02-06

In a significant leap forward for quantum nanophotonics, a team of European and Israeli physicists, introduces a new type of polaritonic cavities and redefines the limits of light confinement. This pioneering work, detailed in a study published today in Nature Materials, demonstrates an unconventional method to confine photons, overcoming the traditional limitations in nanophotonics.

Physicists have long been seeking ways to force photons into increasingly small volumes. The natural length scale of the photon is the wavelength and when a photon is forced into a cavity much smaller than ...