(Press-News.org) Birds can fly— at least, most of them can. Flightless birds like penguins and ostriches have evolved lifestyles that don’t require flight. However, there’s a lot that scientists don’t know about how the wings and feathers of flightless birds differ from their airborne cousins. In a new study in the journal PNAS, scientists examined hundreds of birds in museum collections and discovered a suite of feather characteristics that all flying birds have in common. These “rules” provide clues as to how the dinosaur ancestors of modern birds first evolved the ability to fly, and which dinosaurs were capable of flight.

Not all dinosaurs evolved into birds, but all living birds are dinosaurs. Birds are members of the group of dinosaurs that survived when an asteroid hit the Earth 66 million years ago. Long before the asteroid hit, some of the members of a group of dinosaurs called Penneraptorans began to evolve feathers and the ability to fly.

Members of the Penneraptoran group began to develop feathers before they were able to fly; the original purpose of feathers might have been for insulation or to attract mates. For instance, Velocirpator had feathers, but it couldn’t fly.

Of course, scientists can’t hop in a time machine to the Cretaceous Period to see whether Velociraptors could fly. Instead, paleontologists rely on clues in the animals’ fossilized skeletons, like the size and shape of arm/wing bones and wishbones, along with the shape of any preserved feathers, to determine which species were capable of true, powered flight. For instance, the long primary feathers along the tips of birds’ wings are asymmetrical in birds that can fly, but symmetrical in birds that can’t.

The quest for clues about dinosaur flight led to a collaboration between Jingmai O’Connor, a paleontologist at the Field Museum in Chicago, and Yosef Kiat, a postdoctoral researcher at the Field.

“Yosef, an ornithologist, was investigating traits like the number of different types of wing feathers in relation to the length of arm bone they attach to, and the degree of asymmetry in birds’ flight feathers,” said O’Connor, the museum’s associate curator of fossil reptiles, who specializes in early birds. “Through our collaboration, Yosef is able track these traits in fossils that are 160-120 million years old, and therefore study the early evolutionary history of feathers.”

Kiat undertook a study of the feathers of every order of living birds, examining specimens from 346 different species preserved in museums around the world. As he looked at the wings and feathers from hummingbirds and hawks, penguins and pelicans, he noticed a number of consistent traits among species that can fly. For instance, in addition to asymmetrical feathers, all the flighted birds had between 9 and 11 primary feathers. In flightless birds, the number varies widely— penguins have more than 40, while emus have none. It’s a deceptively simple rule that’s seemingly gone unnoticed by scientists.

“It's really surprising, that with so many styles of flight we can find in modern birds, they all share this trait of having between 9 and 11 primary feathers,” says Kiat. “And I was surprised that no one seems to have found this before.”

By applying the information about the number of primary feathers to the overall bird family tree, Kiat and O’Connor also found that it takes a long time for birds to evolve a different number of primary feathers. “This trait only changes after really long periods of geologic time,” says O’Connor. “It takes a very long time for evolution to act on this trait and change it.”

In addition to modern birds, the researchers also examined 65 fossil specimens representing 35 different species of feathered dinosaurs and extinct birds. By applying the findings from modern birds, the researchers were able to extrapolate information about the fossils. “You can basically look at the overlap of the number of primary feathers and the shape of those feathers to determine if a fossil bird could fly, and whether its ancestors could,” says O’Connor.

For instance, the researchers looked at the feathered dinosaur Caudipteryx. Caudipteryx had 9 primary feathers, but those feathers are almost symmetrical, and the proportions of its wings would have made flight impossible. The researchers said it’s possible that Caudipteryx had an ancestor that was capable of flight, but that trait was lost by the time Caudipteryx arrived on the scene. Since it takes a long time for the number of primary feathers to change, the flightless Caudipteryx retained its 9 primaries. Meanwhile, other feathered fossils’ wings seemed flight-ready— including those of the earliest known bird, Archaeopteryx, and Microraptor, a tiny, four-winged dinosaur that isn’t a direct ancestor of modern birds.

Taken a step further, these data may inform the conversation among scientists about the origins of dinosaurian flight. “It was only recently that scientists realized that birds are not the only flying dinosaurs,” says O’Connor. “And there have been debates about whether flight evolved in dinosaurs just once, or multiple separate times. Our results here seem to suggest that flight only evolved once in dinosaurs, but we have to really recognize that our understanding of flight in dinosaurs is just beginning, and we’re likely still missing some of the earliest stages of feathered wing evolution.”

“Our study, which combines paleontological data based on fossils of extinct species with information from birds that live today, provides interesting insights into feathers and plumage—one of the most interesting evolutionary novelties among vertebrates. Thus, it helps us learn about the evolution of these dinosaurs and highlights the importance of integrating knowledge from different sources for an improved understanding of evolutionary processes," says Kiat.

“Theropod dinosaurs, including birds, are one of the most successful vertebrate lineages on our planet,” says O’Connor. “One of the reasons that they're so successful is their flight. One of the other reasons is probably their feathers, because there's such versatile structures. So any information that can help us understand how these two important features co-evolved that led to this enormous success is really important.”

###

END

A new study shows that it is possible to use machine learning and statistics to address a problem that has long hindered the field of metabolomics: large variations in the data collected at different sites.

“We don’t always know the source of the variation,” said Daniel Raftery, professor of anesthesiology and pain medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. “It could be because the subjects are different with different genetics, diets and environmental exposures. Or it could be the way samples were collected and ...

Legume plants have the unique ability to interact with nitrogen-fixing bacteria in the soil, known as rhizobia. Legumes and rhizobia engage in symbiotic relations upon nitrogen starvation, allowing the plant to thrive without the need for externally supplied nitrogen. Symbiotic nodules are formed on the root of the plant, which are readily colonized by nitrogen-fixing bacteria. The cell-surface receptor SYMRK (symbiosis receptor-like kinase) is responsible for mediating the symbiotic signal from rhizobia perception to formation of the nodule. ...

Modern populations of fallow deer possess hidden cultural histories dating back to the Roman Empire which ought to be factored into decisions around their management and conservation.

New research, bringing together DNA analysis with archaeological insights, has revealed how fallow deer have been repeatedly moved to new territories by humans, often as a symbol of colonial power or because of ancient cultures and religions.

The results show that the animal was first introduced into Britain by the Romans ...

Woods Hole, Mass. (February 12, 2024) – Studying a rock is like reading a book. The rock has a story to tell, says Frieder Klein, an associate scientist in the Marine Chemistry & Geochemistry Department at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI).

The rocks that Klein and his colleagues analyzed from the submerged flanks of the St. Peter and St. Paul Archipelago in the St. Paul’s oceanic transform fault, about 500 km off the coast of Brazil, tells a fascinating and previously unknown story about parts of the geological ...

The replacement of regular salt with a salt substitute can reduce incidences of hypertension, or high blood pressure, in older adults without increasing their risk of low blood pressure episodes, according to a recent study in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. People who used a salt substitute had a 40% lower incidence and likelihood of experiencing hypertension compared to those who used regular salt.

According to the World Health Organization, hypertension is the leading risk factor for cardiovascular disease and mortality. It affects over 1.4 billion adults and results in 10.8 million deaths per year worldwide. One of the ...

Statement Highlights:

The new scientific statement highlights heart disease as the leading cause of death for women and emerging evidence that has identified several gender-specific risk factors for heart disease in women, including complications during pregnancy and premature menopause.

Compared to men, women also have different symptoms of heart disease, are less likely to receive evidence-based therapies and are more likely to have adverse cardiovascular outcomes after a cardiac event.

Targeted public health interventions ...

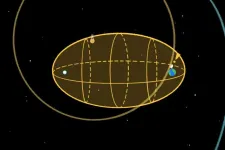

February 12, 2024, Mountain View, CA -- In a paper published in the Astronomical Journal, a team of researchers from the SETI Institute, Berkeley SETI Research Center and the University of Washington reported an exciting development for the field of astrophysics and the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI), using observations from the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) mission to monitor the SETI Ellipsoid, a method for identifying potential signals from advanced civilizations in the ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — The secret to making delicious chocolate with less added sugar is oat flour, according to a new study by Penn State researchers. In a blind taste test, recently published in the Journal of Food Science, 25% reduced-sugar chocolates made with oat flour were rated equally, and in some cases preferred, to regular chocolate. The findings provide a new option for decreasing chocolate’s sugar content while maintaining its texture and flavor.

“We were able to show that there is a range in which you can ...

How well do the algorithms used in the AI-supported analysis of medical images perform their respective tasks? This depends to a large extent on the metrics used to evaluate their performance. An international consortium led by scientists from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT) in Heidelberg has compiled the knowledge available worldwide on the specific strengths, weaknesses and limitations of the various validation metrics. With "Metrics Reloaded", the researchers are ...

Houston, Texas, the epicenter of the global energy market, and the University of Houston – the Energy University – are leading the transition towards a cleaner, more sustainable future with innovative solutions.

With three-quarters of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions stemming from burning fossil fuels for energy, it's clear that the key to curbing emissions lies in reimagining how energy is produced and consumed. In Texas, the shift is already well on its way. Technologies like giant batteries, ...