(Press-News.org) The University of Birmingham has signed a collaboration agreement with Vital Energi to develop and commercialise a range of innovative thermal storage solutions, which will help accelerate decarbonisation within the heating and cooling sector.

The University and Vital Energi will work together over an initial four years to continue the development of thermal storage Intellectual Property (IP) with a view to bringing a number of products to market. As part of the agreement, the University has assigned several IP rights, including a number of patents, to Vital Energi.

The implementation of thermal energy storage is imperative to address the challenges posed by intermittent renewables and enhance the overall reliability and sustainability of energy systems. Just as decarbonisation of electrical generation necessitated the huge growth in electrical storage over the last 10 years, it is expected that thermal energy storage will emerge over the next decade as a key enabler in accelerating the electrification of heat which will form the core of heat decarbonisation.

The collaboration will leverage the combined strengths of Vital Energi's industry experience and the expertise in the team led by Professor Yulong Ding, Chamberlain Chair of Chemical Engineering and the founder of Birmingham Centre for Energy Storage. By fostering a dynamic exchange of ideas and knowledge, both entities aim to accelerate the pace of innovation and commercialisation of thermal storage solutions.

Vital Energi is committed to providing clients and end users with the most efficient and economic decarbonisation solutions and recognise the pivotal role that thermal storage plays in the future to ensure efficient utilisation of energy resources. This collaboration aligns with their aim of delivering environmentally conscious and technologically advanced solutions that address the challenges of today's rapidly evolving energy landscape.

Vital Energi’s Technical Development Director, Chris Taylor, said: “We see thermal energy storage as a core component in the decarbonisation of the heating and cooling sector. Through this collaboration, we aim to bring innovative energy storage to the market and tackle some of the obstacles introduced by an evolving energy system.

“This is an exciting time for Vital and we believe we have found the perfect partners in Professor Ding and his team at the University of Birmingham, and look forward to working together to commercialise their concepts.”

Professor Ding, who is known for inventing novel, commercialisable, technologies for electrical and thermal energy storage, has published over 450 technical papers and filed some 100 patent applications over the past 35 years.

“Globally, thermal energy accounts for over 50% of final energy consumption and is responsible for more than 40% of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions, making it central to achieving net zero emissions. While it is the hardest-to-decarbonise sector, thermal energy storage can help us address this challenge, and I am looking forward to working with Vital Energi to make this happen.” said Professor Ding.

Professor Martin Freer, Director of the Birmingham Energy Institute, added: "This partnership is really exciting as it allows a pathway for the discoveries of Professor Ding and his team to deliver impact in the development of the UK's energy system in the much-needed area of energy storage.

“The University of Birmingham's research is world leading in this area and it presents the opportunity with Vital Energi, who have been fantastic partners, to deliver world leading energy solutions."

END

University of Birmingham signs pioneering collaboration agreement with Vital Energi

2024-02-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Oocytes outsmart toxic proteins to preserve long-term female fertility

2024-02-20

Oocytes are immature egg cells that develop in almost all female mammals before birth. The propagation of future generations depends on this finite reserve of cells surviving for many years without incurring damage. In mice, this can be a period of up to eighteen months, while in humans it can last almost half a century, the average time between birth and menopause. How the cells accomplish this remarkable feat of longevity has been a longstanding question.

Researchers at the Centre for Genomic ...

The Radcliffe Wave is waving

2024-02-20

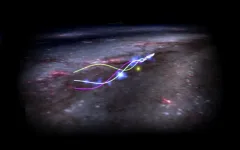

A few years ago, astronomers uncovered one of the Milky Way’s greatest secrets: an enormous, wave-shaped chain of gaseous clouds in our sun’s backyard, giving birth to clusters of stars along the spiral arm of the galaxy we call home.

Naming this astonishing new structure the Radcliffe Wave, in honor of the Harvard Radcliffe Institute, where the undulation was originally discovered, the team now reports in Nature that the Radcliffe Wave not only looks like a wave, but also moves like one – oscillating through space-time much like “the wave” moving through a stadium full of fans.

Ralf Konietzka, the paper’s ...

Examining excess mortality associated with the pandemic for renters threatened with eviction

2024-02-20

About The Study: Housing instability, as measured by eviction filings, was associated with a significantly increased risk of death over the first 20 months of the COVID-19 pandemic in this study that included 282,000 renters who received an eviction filing. Eviction prevention efforts may have reduced excess mortality for renters during this period.

Authors: Nick Graetz, Ph.D., of Princeton University in Princeton, New Jersey, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit ...

Fresh meat: New biosensor accurately and efficiently determines meat freshness

2024-02-20

WASHINGTON, Feb. 20, 2024 — The freshness of animal meat is an essential property determining its quality and safety. With advanced technology capable of preserving food for extended periods of time, meat can be shipped around the globe and consumed long after an animal dies. As global meat consumption rates increase, so too does the demand for effective measures for its age.

Despite the technological advances keeping meat fresh for as long as possible, certain aging processes are unavoidable. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) ...

Large, diverse genetic study of glaucoma implicates vascular and cancer-related genes

2024-02-20

An international genetic study using multiancestry biobanks has identified novel genetic locations associated with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), the most common type of glaucoma and the leading cause of irreversible blindness globally. The findings, published Feb. 20 in Cell Reports Medicine, detail ancestry- and sex-specific genetic loci associated with POAG and implicate vascular and cancer-related genes in POAG risk.

“Although there has been significant progress using genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to explore the genetic pathophysiology of glaucoma in humans, there is still a lack of understanding of the underlying ...

HPV vaccination among young adults before and during the pandemic

2024-02-20

About The Study: The results of this study suggest that human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage among young adults did not increase during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with prior years. This finding likely reflects pandemic-related disruptions in initiating the HPV vaccine among young adults.

Authors: Kalyani Sonawane, Ph.D., of the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.56875)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for ...

Historical redlining, persistent mortgage discrimination, and race in breast cancer outcomes

2024-02-20

About The Study: In a study of 1,764 women with breast cancer, living in a historically redlined area was associated with increased odds of a diagnosis of estrogen receptor–negative breast cancer in non-Hispanic Black women and increased odds of late-stage diagnosis in non-Hispanic white women. Persistent mortgage discrimination was associated with an increase in breast cancer mortality in non-Hispanic white women, and non-Hispanic Black women were more likely to die of breast cancer no matter where they lived.

Authors: Jasmine M. Miller-Kleinhenz, Ph.D., of Emory University in Atlanta, is the corresponding author.

To ...

Ancient genomes reveal Down Syndrome in past societies

2024-02-20

For many years, researchers at MPI-EVA have been collecting and analyzing ancient DNA from humans who lived during the past tens of thousands of years. Analyzing these data has allowed the researchers to trace the movement and mixing of people, and even to uncover ancient pathogens that affected their lives. However, a systematic study of uncommon genetic conditions had not been attempted. One of those uncommon conditions, known as Down Syndrome, affects nowadays around one in 1,000 births.

To their surprise, Adam “Ben” Rohrlach and colleagues identified six individuals ...

Can a single brain region encode familiarity and recollection?

2024-02-20

NEW YORK, NY — The human brain has the extraordinary ability to rapidly discern a stranger from someone familiar, even as it can simultaneously remember details about someone across decades of encounters. Now, in mouse studies, scientists at Columbia's Zuckerman Institute have revealed how the brain elegantly performs both tasks.

“These findings are the first evidence that a single population of neurons can use different codes to represent novel and familiar individuals,” said co-corresponding author Stefano Fusi, PhD, professor of neuroscience at Columbia’s Vagelos College of Physicians and ...

Pesticides found in kale but at low risk levels

2024-02-20

Kale fans can rest easy knowing pesticides used to grow the hearty greens are unlikely to end up in their salads or smoothies, a new chemical analysis of the superfood suggests.

Conducting novel tests that provide the most complete picture to date of a crop’s chemical makeup, the Johns Hopkins–led team found several pesticides and compounds in Maryland-farmed kale—but no cause for alarm.

“We do see minute traces of pesticides in the kale, but the levels we found are so much lower ...