(Press-News.org) Among the vast expanse of Antarctica lies the Thwaites Glacier, the world’s widest glacier measuring about 80 miles on the western edge of the continent. Despite its size, the massive landform is losing about 50 billion tons of ice more than it is receiving in snowfall, which places it in a precarious position in respect to its stability.

Accelerating ice loss has been observed since the 1970s, but it is unclear when this significant melting initiated – until now. A new study published in the journal PNAS, led by researchers at the University of Houston, suggests that significant glacial retreat began in the 1940s. Their results on the Thwaites Glacier coincide with previous work that studied retreat on Pine Island Glacier and found glacial retreat began in the ‘40s as well.

“What is especially important about our study is that this change is not random nor specific to one glacier,” said Rachel Clark, corresponding author, who graduated from UH last year with a doctorate in geology. “It is part of a larger context of a changing climate. You just can’t ignore what’s happening on this glacier.”

Clark and the study authors posit that the glacial retreat was likely kicked off by an extreme El Niño climate pattern that warmed the west Antarctic. Since then, the authors say, the glacier has not recovered and is currently contributing to 4% of global sea-level rise.

“It is significant that El Niño only lasted a couple of years, but the two glaciers, Thwaites and Pine Island, remain in significant retreat,” said Julia Wellner, UH associate professor of geology and U.S. lead investigator of the Thwaites Offshore Research project, or THOR, an international collaboration whose team members are authors of the study.

“Once the system is kicked out of balance, the retreat is ongoing,” she added.

Their findings also make it clear the retreat at the glaciers’ grounding zone, or the area where the glaciers lose contact with the seabed and start to float, was due to external factors.

“The finding that both Thwaites Glacier and Pine Island Glacier share a common history of thinning and retreat corroborates the view that ice loss in the Amundsen Sea sector of the West Antarctic ice sheet is predominantly controlled by external factors, involving changes in ocean and atmosphere circulation, rather than internal glacier dynamics or local changes, such as melting at the glacier bed or snow accumulation on the glacier surface,” said Claus-Dieter Hillenbrand, U.K. lead investigator of THOR and study co-author.

“A significant implication of our findings is that once an ice sheet retreat is set in motion, it can continue for decades, even if what started it gets no worse,” added James Smith, a marine geologist at the British Antarctic Survey and study co-author. “It is possible that the changes we see today on Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers – and potentially across the entire Amundsen Sea embayment – were essentially set in motion in the 1940s.”

Dating of Sediment Cores Plays Key Role in Study

Clark and the team used three primary methods to reach their conclusion. One of those methods was marine sediment core collection that was closer to the Thwaites Glacier than ever before. They retrieved the cores during their trip to the Amundsen Sea near Thwaites in early 2019 aboard the Nathaniel B. Palmer icebreaker and research vessel. The researchers then used the cores to reconstruct the glacier’s history from the early Holocene epoch to the present. The Holocene is the current geological epoch that began after the last ice age, roughly 11,700 years ago.

CT scans were used to take x-rays of the sediment to gather details from its history. Geochronology, or the science of dating earth materials, was then used to reach the conclusion that significant ice melt began in the ‘40s.

Clark used 210Pb (lead-210), an isotope that’s naturally buried in the sediment cores and is radioactive, as the most important isotope in her geochronology. This process is similar to radiocarbon dating, which measures the age of organic materials as far back as 60,000 years.

“But lead-210 has a short half-life of about 20 years, whereas something like radiocarbon has a half-life of about 5,000 years,” Clark said. “That short half-life allows us to build a timeline for the past century that’s detailed.”

This methodology is important because although satellite data exists to help scientists understand glacial retreat, these observations only go as far back as a few decades, a time frame that is too short to determine how Thwaites responds to ocean and atmosphere changes. Pre-satellite records are needed for scientists to understand the glacier’s longer-term history, which is why sediment cores are used.

Study Informs Future Modeling to Reduce Uncertainty of Sea-Level Rise

Thwaites Glacier plays a vital role in regulating the West Antarctic ice sheet stability and, thus, global sea-level rise, according to Antarctic researchers.

“The glacier is significant not only because of its contribution to sea-level rise but because it is acting as a cork in the bottle holding back a broader area of ice behind it,” Wellner said. “If Thwaites is destabilized, then there’s potential for all the ice in West Antarctica to become destabilized.”

If Thwaites Glacier were to collapse entirely, global sea levels are predicted to rise by 65 cm (25 in).

“Our study helps to better understand what factors are most critical in driving thinning and retreat of glaciers draining the West Antarctic ice sheet into the Amundsen Sea,” Hillenbrand said. “Therefore, our results will improve numerical models that attempt to predict the magnitude and rate of future Antarctic ice sheet melting and its contributions to sea levels.”

Researchers with THOR are part of an even larger initiative, the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, a joint U.S.-U.K. partnership to reduce uncertainty in the projection of sea-level rise from Thwaites Glacier.

The study’s authors are Clark, Wellner and Georgina Garcia-Barrera of the University of Houston; Hillenbrand, James Smith, Robert Larter and Kelly Hogan of the British Antarctic Survey; Rebecca Totten, Asmara Lehrmann and Victoria Fitzgerald of the University of Alabama; Lauren Simkins and Allison Lepp of the University of Virginia; Alastair Graham of the University of South Florida; Frank Nitsche of Columbia University; James Kirkham of the University of Cambridge and the British Antarctic Survey; Werner Ehrmann of the University of Leipzig; and Lukas Wacker of Ion Beam Physics.

END

New discovery suggests significant glacial retreat in West Antarctica began in 1940s

Published study reports thwaites and pine island glaciers share common history of thinning

2024-02-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Butterflies mimic each other’s flight behaviour to avoid predators

2024-02-26

Researchers have shown that inedible species of butterfly that mimic each others’ colour patterns have also evolved similar flight behaviours to warn predators and avoid being eaten.

It is well known that many inedible species of butterfly have evolved near identical colour patterns, which act as warning signals to predators so the butterflies avoid being eaten.

Researchers have now shown that these butterflies have not only evolved similar colour patterns, but that they have also evolved similar ...

What math tells us about social dilemmas

2024-02-26

Human coexistence depends on cooperation. Individuals have different motivations and reasons to collaborate, resulting in social dilemmas, such as the well-known prisoner's dilemma. Scientists from the Chatterjee group at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) now present a new mathematical principle that helps to understand the cooperation of individuals with different characteristics. The results, published in PNAS, can be applied to economics or behavioral studies.

A group of neighbors shares a driveway. Following a heavy snowstorm, the entire driveway is covered in snow, requiring clearance for daily activities. ...

Protecting fish doesn’t have to mean neglecting people, study concludes

2024-02-26

BEAUFORT, N.C. –With fish stocks declining globally, more than 190 countries recently made a commitment to protect about a third of the world’s oceans within “Marine Protected Areas,” or MPAs by the year 2030. But these designated areas of the ocean where fishing is either regulated or outright banned can come at a huge cost to some coastal communities, according to a new analysis.

To help prepare for the expansion of MPAs, an international team of researchers from Duke University, Florida State ...

What will it take for China to reach carbon neutrality by 2060?

2024-02-26

To become carbon neutral by 2060, as mandated by President Xi Jinping, China will have to build eight to 10 times more wind and solar power installations than existed in 2022. Reaching carbon neutrality will also require major construction of transmission lines.

China land use policies will also have to be more coordinated and focused on a nation-wide scale rather than be left to ad hoc decisions by local governments. That’s because 80% of solar power and 55% of wind power will have to be built within 100 miles of major population centers.

These are the conclusions of a new study from ...

A new theoretical development clarifies water's electronic structure

2024-02-26

There is no doubt that water is significant. Without it, life would never have begun, let alone continue today – not to mention its role in the environment itself, with oceans covering over 70% of Earth.

But despite its ubiquity, liquid water features some electronic intricacies that have long puzzled scientists in chemistry, physics, and technology. For example, the electron affinity, i.e. the energy stabilization undergone by a free electron when captured by water, has remained poorly characterized from an experimental ...

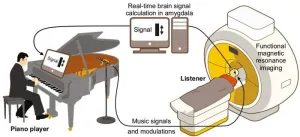

Live music emotionally moves us more than streamed music

2024-02-26

How does listening to live music affect the emotional center of our brain? A study carried out at the University of Zurich has found that live performances trigger a stronger emotional response than listening to music from a device. Concerts connect performers with their audience, which may also have to with evolutionary factors.

Music can have a strong effect on our emotions. Studies have shown that listening to recorded music stimulates emotional and imaginative processes in our brain. But what happens when we listen to music in a live setting, for example at a music festival, at the opera or a folk concert? ...

Detroit research team to develop novel strategies to identify genetic contributions to cancer risk and overcome barriers to genetic testing for African Americans

2024-02-26

DETROIT – A team of researchers from Wayne State University and the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute has received a five-year, $9.6 million grant from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health for the study “Genetic Variation in Cancer Risk and Outcomes in African Americans.” This is a Program Project Grant that includes three large studies. The team will work to improve the identification and clinical management of hereditary and multiple primary cancers in African Americans, a population that is currently underrepresented in genetic research.

According to Ann Schwartz, Ph.D., principal investigator of the project, professor and ...

Vaping can increase susceptibility to infection by SARS-CoV-2

2024-02-26

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- Vapers are susceptible to infection by SARS-CoV-2, the virus that spreads COVID-19 and continues to infect people around the world, a University of California, Riverside, study has found.

The liquid used in electronic cigarettes, called e-liquid, typically contains nicotine, propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, and flavor chemicals. The researchers found propylene glycol/vegetable glycerin alone or along with nicotine enhanced COVID-19 infection through different mechanisms.

Study results appear in the American Journal of Physiology.

The researchers ...

Dissecting the roles for excitatory and inhibitory neurons in STXBP1 encephalopathy

2024-02-26

A recent study from Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital has discovered inhibitory and excitatory neurons play distinct roles in the pathogenesis of STXBP1 encephalopathy, one of the top five causes of pediatric epilepsies and among the most frequent causes of neurodevelopmental disorders. This early-onset disorder is caused by spontaneous mutations in the syntaxin-binding protein 1 (STXBP1) gene. While STXBP1 gene variants impair both excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission, this study led by Dr. Mingshan Xue, associate professor at Baylor and principal investigator at the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute (Duncan ...

Boston College biologist awarded $2.5-million NIH grant to explore the role of viral insulins and potential applications to cancers

2024-02-26

Chestnut Hill, Mass (2/26/2024) – Boston College Assistant Professor of Biology Emrah Altindis has been awarded a five-year, $2.5-million grant from the National Institutes of Health to study viral insulins and mechanisms related to IGF-1 receptor protein inhibition and its potential applications in cancer treatment.

Altindis said he and the researchers in his lab will use the grant to learn more about how to use specific viral insulins – particularly insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) – to inhibit IGF-1 receptor action, which is increased in a range ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

Muscular strength and mortality in women ages 63 to 99

[Press-News.org] New discovery suggests significant glacial retreat in West Antarctica began in 1940sPublished study reports thwaites and pine island glaciers share common history of thinning