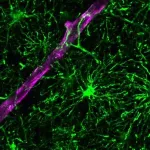

(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA (February 28, 2024)—The brain is typically depicted as a complex web of neurons sending and receiving messages. But neurons only make up half of the human brain. The other half—roughly 85 billion cells—are non-neuronal cells called glia. The most common type of glial cells are astrocytes, which are important for supporting neuronal health and activity. Despite this, most existing laboratory models of the human brain fail to include astrocytes at sufficient levels or at all, which limits the models’ utility for studying brain health and disease.

Now, Salk scientists have created a novel organoid model of the human brain—a three-dimensional collection of cells that mimics features of human tissues—that contains mature, functional astrocytes. With this astrocyte-rich model, researchers will be able to study inflammation and stress in aging and diseases like Alzheimer’s with greater clarity and depth than ever before. Already, the researchers have used the model to reveal a relationship between astrocyte dysfunction and inflammation, as well as a potentially druggable target for disrupting that relationship.

The findings were published in Nature Biotechnology on February 28, 2024.

“Astrocytes are the most abundant type of glial cell in the brain, yet they have been underrepresented in organoid models of the brain,” says senior author Rusty Gage, professor and Vi and John Adler Chair for Research on Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disease at Salk. “Our model rectifies this deficit, offering a glial-enriched human brain organoid that can be used to explore the many ways that astrocytes are essential for brain function, and how they respond to stress and inflammation in various neurological conditions.”

In the last 10 years, organoids have emerged as a prevalent tool to bridge the gap between cell and human studies. Organoids can mimic human development and organ generation better than other laboratory systems, allowing researchers to study how drugs or diseases affect human cells in a more realistic setting. Brain organoids are typically grown in culture dishes, but their limited capacity to efficiently produce certain brain cells like astrocytes has remained problematic.

Astrocytes develop through the same pathway as neurons, beginning first as a neuronal stem cell until a molecular switch flips and turns the cell’s fate from neuron to astrocyte. To create a brain organoid with abundant astrocyte populations, the team looked for a way to trigger this switch.

To do this, the researchers delivered specific gliogenic compounds to the organoid, looking to see if they would promote astrocyte formation. The team then began running tests to see whether astrocytes had developed and, if they had, how many and to what extent they had matured.

The brain organoids cultured in a dish still lacked the microenvironment and the neuronal structural arrangement of a human brain. To create a more human brain-like environment, researchers transplanted the organoids into mouse models, allowing them to further develop over several months.

"Our transplanted organoid model produced more sophisticated and differentiated astrocyte populations than would have been possible with older models,” says co-first author Lei Zhang, a former postdoctoral researcher in Gage’s lab. “What was really exciting is that we observed order in the organoids. The organization of functional cell groups in the human brain is very difficult to mimic in a laboratory setting, but these astrocytes in our organoid model were doing just that.”

After observing astrocyte subtype development and maturation in the transplanted organoids, the researchers aimed to investigate the role of astrocytes in the process of neuroinflammation. Aging and age-related neurological diseases have strong ties to the immune system and inflammation, and whether astrocytes are also involved in this relationship has long been a question for neuroscientists.

To test this, the researchers introduced a proinflammatory compound into the transplanted organoids and found that a subtype of astrocytes became activated and promoted further proinflammatory pathways. Additionally, they found that a molecule called CD38 was crucial in mediating metabolic and energetic stress in those reactive astrocytes. Knowing CD38 signaling plays this important role suggests that CD38 inhibitors may be able to alleviate the neuroinflammation and related stresses caused by these reactive astrocytes, says Gage.

“We have created a human brain model for research that is more similar to its real-life counterpart than ever before—it has all the major astrocyte subclasses found in the human cortex,” says co-first author Meiyan Wang, a postdoctoral researcher in Gage’s lab. “With this model, we have already found a link between inflammation and astrocyte dysfunction and, in the process, revealed CD38 as a potentially druggable target to disrupt that link.”

Their findings build on another recent model developed in the lab that featured a different glial cell type, called microglia. While this astrocyte-rich model is the most advanced yet, the team is already looking to improve and expand on their organoid model by incorporating additional brain cell types and promoting further cell maturation. In the meantime, they aim to use the sophisticated model to investigate brain function and dysfunction in new detail, with the hopes that their findings will lead to new interventions and therapeutics for neurological conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

Other authors include Sammy Weiser Novak, Jingting Yu, Iryna Gallina, Lynne Xu, Christina Lim, Sarah Fernandes, Maxim Shokhirev, April Williams, Monisha Saxena, Shashank Coorapati, Sarah Parylak, Cristian Quintero, Elsa Molina, and Leonardo Andrade of Salk; and Uri Manor, who was a Salk research professor at the time of the study.

The work was supported by the American Heart Association, a Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group Grant (#19PABHI34610000), the JPB Foundation, Annette C. Merle-Smith, Lynn and Edward Streim, the Milky Way Foundation, Ray and Dagmar Dolby Family Fund, National Institutes of Health (R37 AG072502-03, P30 AG062429-05, P30 AG068635-04, R01 AG070154-04, AG056306-07, P01 AG051449-08, NCI CCSG: P30 014195, NINDS R24 Core Grant, National Eye Institute), NGS Core Facility, GT3 Core Facility, Razavi Newman Integrative Genomics and Bioinformatics Core Facility, Chapman Foundation, Waitt Foundation, a Brain & Behavior Research Foundation NARSAD Young Investigator Grant, and a Pioneer Fund Postdoctoral Scholar Award.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

Unlocking the secrets of life itself is the driving force behind the Salk Institute. Our team of world-class, award-winning scientists pushes the boundaries of knowledge in areas such as neuroscience, cancer research, aging, immunobiology, plant biology, computational biology, and more. Founded by Jonas Salk, developer of the first safe and effective polio vaccine, the Institute is an independent, nonprofit research organization and architectural landmark: small by choice, intimate by nature, and fearless in the face of any challenge. Learn more at www.salk.edu.

END

More than just neurons: A new model for studying human brain inflammation

Salk scientists create human brain organoid model with abundant astrocytes to study stress and inflammation in neurological diseases like Alzheimer’s

2024-02-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Urgent need to develop best practices to advance use of AI in cardiovascular care

2024-02-28

Statement Highlights:

The American Heart Association encourages research and development of artificial intelligence (AI) and other related tools and services that may support and enable more precise approaches to cardiovascular and stroke research, prevention and care.

Academia, industry and governments worldwide are pouring resources into developing AI-based tools to transform how and when health care is delivered.

While promising research is beginning to emerge in many areas of cardiovascular medicine, AI-based tools, algorithms and systems of care have not yet been proven to improve care enough to justify widespread use.

AI and machine learning digital tools currently exist that ...

Smoking cannabis associated with increased risk of heart attack, stroke

2024-02-28

Smoking cannabis associated with increased risk of heart attack, stroke

NIH-funded observational study shows risk grows sharply with more frequent use

Frequent cannabis smoking may significantly increase a person’s risk for heart attack and stroke, according to an observational study supported by the National Institutes of Health. The study, published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, uses data from nearly 435,000 American adults, and is among the largest ever to explore the relationship ...

NYUAD researchers highlight a potential flaw in operating room ventilation that increases risk of infection by COVID-19

2024-02-28

● Simple modifications to ventilation systems improve airflow, making operations safer for both patients and surgical teams

● This research was conducted in close collaboration with a team of surgeons from Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi (CCAD)

Abu Dhabi, UAE, February 28, 2024: NYU Abu Dhabi (NYUAD) engineers studying ventilation systems in surgical operating theaters have found that traditional ventilation systems may inadvertently facilitate the circulation of aerosolized pathogen-carrying particles. This, as a result, puts surgical teams at a higher risk of infection by COVID-19 and other airborne diseases.

Using basic engineering tools, including ...

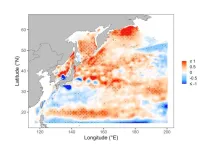

Climate change shrinking fish

2024-02-28

Fish weight in the western North Pacific Ocean dipped in the 2010s due to warmer water limiting food supplies, according to a new study at the University of Tokyo. Researchers analyzed the individual weight and overall biomass of 13 species of fish. In the 1980s and 2010s, the fish were lighter. They attributed the first period of weight loss to greater numbers of Japanese sardine, which increased competition with other species for food. During the 2010s, while the number of Japanese sardine and chub mackerel moderately increased, the effect of climate change warming the ocean appears to have resulted ...

Yeast and kelp flies can replace fishmeal in feed

2024-02-28

Kelp flies and marine yeast cultivated on by-products from the seafood industry can be used in feed for farmed salmon. Replacing fishmeal and soybeans can create more sustainable and circular food production, according to a thesis from the University of Gothenburg.

Food from aquaculture, such as farmed fish, is the food industry’s fastest growing sector. One key reason is that this is a nutritious and protein-rich food that is generally more sustainably produced than protein from land animals.

However, fish farming also has challenges. One is obtaining sufficient amounts of sustainable high-quality feed. Currently, fish feed accounts for about ...

Meltwater in the North Atlantic can lead to European summer heatwaves, study finds

2024-02-28

Scientists from the National Oceanography Centre (NOC) have discovered that increased meltwater in the North Atlantic can trigger a chain of events leading to hotter and drier European summers.

The paper, which will be published in the European Geosciences Union’s open access journal Weather and Climate Dynamics, suggests that European summer weather is predictable months to years in advance, due to higher levels of freshwater in the North Atlantic.

Discussing the implications, lead author Marilena Oltmanns, Research Scientist at the National Oceanography Centre, said: “While the UK and northern Europe experienced unusually cool and wet weather in Summer 2023, Greenland experienced ...

A threat to what is ours: How Japanese people react to perceived territorial infringements

2024-02-28

Osaka, Japan – Throughout the world, it is common for threats to national sovereignty or territorial integrity to stir up strong emotions among the public. Now, researchers from Japan have found that the strength of the reaction to such threats can break down along political lines in interesting ways.

In a study published in Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, researchers from Osaka University have revealed that the Japanese public is highly sensitive to what are known as “collective ownership ...

Experiment captures why pottery forms are culturally distinct

2024-02-28

Potters of different cultural backgrounds learn new types differently, producing cultural differences even in the absence of differential cultural evolution. The Kobe University-led research has implications for how we evaluate the difference of archaeological artifacts across cultures.

Cultural artifacts differ between cultures but are relatively stable within cultures. This makes pottery, and in particular its form, an important archaeological indicator to determine the presence of different cultural groups in specific locations and how they influenced each other over time. But where do such culturally stable variations arise from? The typical explanation for this is through “selective ...

A liking for licking

2024-02-28

HONG KONG (28 Feb 2024) — Unique insights into the social lives of cattle revealed in a new study by scientists at City University of Hong Kong (CityUHK) can enhance our understanding of animal behaviour and welfare. The study suggests that sex and social status influence social grooming (where one animal licks another, also known as allogrooming) among free-ranging feral cattle in Hong Kong.

The CityUHK researchers found that feral cattle performed preferential grooming of certain individuals and, in particular, that more dominant females received more grooming. This asymmetrical distribution of licking also applied to whom male cattle decided to ...

Scientists provide first detailed estimates of how much sediment is supplied to coral islands from the reef system

2024-02-28

Scientists have produced the first detailed estimates of how much sediment is transported onto the shores of coral reef islands, and how that might enable them to withstand the future threats posed by climate change.

Coral reef islands are low-lying accumulations of sand and gravel-sized sediment deposited on coral reef surfaces.

The sediments are derived from the broken down remains of corals and other organisms that grow on the surrounding reef. Therefore, the rate of supply of sediment from reefs is a critical control on island formation and future change.

The international team of researchers used data available for 28 reef islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, widely ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal reports faster robot-assisted brain angiography

New study clarifies how temperature shapes sex development in leopard gecko

Major discovery sparks chain reactions in medicine, recyclable plastics - and more

Microbial clues uncover how wild songbirds respond to stress

Researchers develop AI tools for early detection of intimate partner violence

Researchers develop AI tool to predict patients at risk of intimate partner violence

New research outlines pathway to achieve high well-being and a safe climate without economic growth

How an alga makes the most of dim light

Race against time to save Alpine ice cores recording medieval mining, fires, and volcanoes

Inside the light: How invisible electric fields drive device luminescence

A folding magnetic soft sheet robot: Enabling precise targeted drug delivery via real-time reconfigurable magnetization

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for March 2026

New tools and techniques accelerate gallium oxide as next-generation power semiconductor

Researchers discover seven different types of tension

Report calls for AI toy safety standards to protect young children

VR could reduce anxiety for people undergoing medical procedures

Scan that makes prostate cancer cells glow could cut need for biopsies

Mechanochemically modified biochar creates sustainable water repellent coating and powerful oil adsorbent

New study reveals hidden role of larger pores in biochar carbon capture

Specialist resource centres linked to stronger sense of belonging and attainment for autistic pupils – but relationships matter most

Marshall University, Intermed Labs announce new neurosurgical innovation to advance deep brain stimulation technology

Preclinical study reveals new cream may prevent or slow growth of some common skin cancers

Stanley Family Foundation renews commitment to accelerate psychiatric research at Broad Institute

What happens when patients stop taking GLP-1 drugs? New Cleveland Clinic study reveals real world insights

[Press-News.org] More than just neurons: A new model for studying human brain inflammationSalk scientists create human brain organoid model with abundant astrocytes to study stress and inflammation in neurological diseases like Alzheimer’s