(Press-News.org) Neuroscientists at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center have found that an often-overlooked type of brain cell called glia has more of a role in brain function than previously thought.

In the journal Cell Reports, Fred Hutch neuroscientist Aakanksha Singhvi, PhD, and her team report that a single glial cell uses different molecules to communicate with different neurons. Careful clustering of these molecules ensures that the glial cell can conduct a distinct “conversation” with each neuron. Through these molecular facilitators, glia can influence how neurons respond to environmental cues like temperature and smell.

Cell Reports published the study online Feb. 27.

“It’s the first very clear indication that a glial cell is going to put specific molecules to specific contact sites to regulate those neurons, at the single-cell level, with consequences to how the animal will behave,” said Singhvi, who is an assistant professor in the Basic Sciences Division at Fred Hutch.

Glial cells make up about half of the cells in the brain, but the other half of the cells — neurons — typically get the most of our attention for their central role in our thoughts, sensations and behaviors. Less glitzy than neurons that literally pulse with electricity, glia seemed to play a purely supporting role. Neuroscientists dismissed them a mere “glue” that help neurons stick together, or “nursemaids” that provide neurons sustenance but not guidance.

Singhvi is among the cadre of neuroscientists leading the charge to reevaluate the importance of glia.

“In the last few years there has been growing appreciation that glial cells may contribute to many diseases of the brain, from epilepsy to Alzheimer’s,” Singhvi said. “To have a more holistic and clinically-relevant picture of brain function, we need to go back to basics and more fully understand how glia and neurons work together.”

To unearth glial cells’ basic biology, Singhvi helped develop the use of Caenorhabditis elegans, which are tiny, transparent worms (also called nematodes). Each worm has exactly the same number of cells, including 302 neurons per animal, and only 56 glia. While we may seem to have little in common with worms, their neurons and glia work much like ours.

Singhvi and Sneha Ray — first author of the Cell Reports study and a graduate student in Singhvi’s lab — focused on one of these glial cells called amphid sheath (AMsh) to see how they interacted with a sensory neuron called AFD, which senses temperature for C. elegans.

Using high-powered microscopes to zero in on individual neurons and glia, the researchers looked for a protein called KCC-3 that Singhvi had previously discovered helps with signaling across cell membranes. The researchers quickly saw that KCC-3 was not distributed equally along the glial cell’s membrane. Instead, the protein clustered in one spot along the interface between the glial cell (AMsh) and the sensory neuron (AFD).

“We realized it’s sitting next to the temperature-sensing neuron — but not any of the others — which is essentially the glial cell knowing a half a micron [millionth of a meter] difference between the two neurons,” Singhvi said.

The team detected at least three types of molecular clusters that connect the AMsh glia to different sensory neurons.

Ray and Singhvi also found that even though every neuron enveloped by AMsh senses a different environmental cue, the glial cell can help integrate information across circuits and allow neurons within one sensory circuit (like temperature) to influence the function of neurons within a different circuit (like those that smell specific odors). In this way, a single glial cell can help the worm respond to the bigger environmental picture, instead of merely helping neurons relay individual external cues.

“When you think about what it takes to be a nematode, it’s very complicated,” Singhvi said.

What does a worm do when it encounters a tantalizing scent that signals food — right when its environment starts getting dangerously warm? It must balance these different inputs and make a decision.

“The worm won’t burn — it’s too smart to burn,” Singhvi said.

And the compartmentalization that she and Ray uncovered is likely critical to a nematode’s — or human’s — ability to weigh important factors like heat and smell, she said. This allows the animal to have multiple circuits working properly at the same time without confusing cross connections.

For possible applications to human brain health, Singhvi noted that the same KCC-3 protein she studies in nematodes is also essential for brain function in humans. Disruptions of KCC-3 is linked to a severe brain development disorder called agenesis of the corpus callosum or Anderman Syndrome, and to seizure susceptibility and neurodegeneration. Differences in brain circuits is linked to conditions such as autism, epilepsy and schizophrenia.

“Our brains routinely process multiple inputs or sensory cues in parallel,” Singhvi said. “Our research showing that glia can be conduits between brain circuits will help us understand the different ways that the circuits can be disrupted.”

This work was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Simons Foundation, Barbara Stephanus, George Brown, the Van Sloun Foundation, the Esther A. & Joseph Klingenstein Fund, the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research, the American Federation for Aging Research and the Brain Research Foundation.

END

Molecular clusters on glial cells show they are more than our brain’s ‘glue’

Underappreciated glia play central role in sensory response

2024-02-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

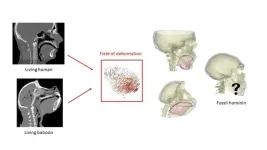

New method enables 3D tongue modelling, for example from fossilized hominin skulls, and might help understand the emergence of human speech

2024-02-28

New method enables 3D tongue modelling, for example from fossilized hominin skulls, and might help understand the emergence of human speech.

####

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1011808

Article Title: Predicting primate tongue morphology based on geometrical skull matching. A first step towards an application on fossil hominins

Author Countries: France

Funding: This work is a production of the members of the team "Origins of speech" hosted at Sorbonne University - Institut des Sciences du Calcul et des Données. The funders had no role in study design, data collection ...

Pew names scientists from 6 countries as 2024 fellows in marine conservation

2024-02-28

PHILADELPHIA—The Pew Charitable Trusts announced today that it has selected six distinguished researchers as recipients of the 2024 Pew fellowship in marine conservation. The researchers—from Canada, China, Denmark, the Philippines, the United Kingdom, and the United States—join a community of more than 200 Pew marine fellows who have undertaken projects to deepen our understanding of the ocean and advance the sustainable use of marine resources.

“The world’s oceans have never been under greater threat. Humankind relies on healthy oceans in countless ways,” said Susan K. Urahn, Pew’s ...

For Type II diabetes prevention, tap into AI

2024-02-28

AUSTIN, Texas — Better prevention of Type II diabetes could save both lives and money. The U.S. spends over $730 billion a year — nearly a third of all health care spending — on treating preventable diseases like diabetes.

For the 98 million adults who are prediabetic and at risk of developing Type II diabetes, preventive treatments such as the drug metformin can help stave off the disease. But the medicines are expensive. With limited budgets, insurers and health care facilities need to allocate them to the patients they can help the most.

Currently, a health ...

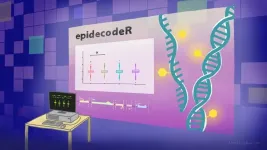

New tool helps decipher gene behaviour

2024-02-28

Scientists have extensively researched the structure and sequence of genetic material and its interactions with proteins in the hope of understanding how our genetics and environment interact in diseases. This research has partly focused on ‘epigenetic marks’, which are chemical modifications to DNA, RNA, and the associated proteins (known as histones).

Epigenetic marks influence when and how genes get switched on or off. They can also instruct cells about how to interpret and use genetic information, influencing various cellular processes. Changes in epigenetic marks therefore significantly impact gene regulation and cellular ...

Think smoking cannabis won’t damage your heart? Think again

2024-02-28

The cardiac risks of smoking marijuana are comparable to those of smoking tobacco, according to researchers at UC San Francisco, who warn that the increasing use of cannabis across the country could lead to growing heart health problems.

The study found that people who used cannabis daily had a 25% increased risk of heart attack and a 42% increased risk of stroke compared to non-users.

Cannabis has become more popular with legalization. Recreational use is now permitted in 24 states, and as of 2019, nearly 4% said they used it daily and 18% used it annually. That is a significant increase since 2002, when 1.3% said they used it daily and 10.4% ...

Early-life exposure to air pollution and childhood asthma cumulative incidence

2024-02-28

About The Study: In this study of 5,279 children, early life air pollution was associated with increased asthma incidence by early and middle childhood, with higher risk among minoritized families living in urban communities characterized by fewer opportunities and resources and multiple environmental co-exposures. Reducing asthma risk in the U.S. requires air pollution regulation and reduction combined with greater environmental, educational, and health equity at the community level.

Authors: Antonella Zanobetti, Ph.D., ...

Hourly heat exposure and acute ischemic stroke

2024-02-28

About The Study: The results of this study of 82,000 patients with acute ischemic stroke suggest that hourly heat exposure is associated with increased risk of acute ischemic stroke onset. This finding may benefit the formulation of public health strategies to reduce cerebrovascular risk associated with high ambient temperature under global warming.

Authors: Jing Zhao, Ph.D., and Haidong Kan, Ph.D., of Fudan University in Shanghai, China, are the corresponding authors.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.0627)

Editor’s ...

CityUHK develops world-leading microwave photonics chip for high-speed signal processing

2024-02-28

A research team led by Professor Wang Cheng from the Department of Electrical Engineering (EE) at City University of Hong Kong (CityUHK) has developed a world-leading microwave photonic chip that is capable of performing ultrafast analog electronic signal processing and computation using optics.

The chip, which is 1,000 times faster and consumes less energy than a traditional electronic processor, has a wide range of applications, covering 5/6G wireless communication systems, high-resolution radar systems, artificial intelligence, computer vision, and image/video processing.

The team's research findings were published in the prestigious scientific ...

The “switch” that keeps the immune system from attacking the body

2024-02-28

A microscopic battle rages in our bodies, as our cells constantly fend off invaders through our immune system, a complex system of cells and proteins designed to protect us from harmful pathogens. One of its central components is the enzyme cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS), which acts as a sentinel, detecting foreign DNA and initiating an immune response.

However, the immune system requires precise regulation to prevent cGAS from mistakenly attacking the body's own tissues, leading to autoimmune disorders, which now affect about 10% of the global population.

Previous studies have revealed a little of how this ...

Study unravels the earliest cellular genesis of lung adenocarcinoma

2024-02-28

HOUSTON ― Researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center built a new atlas of lung cells, uncovering new cellular pathways and precursors in the development of lung adenocarcinoma, the most common type of lung cancer. These findings, published today in Nature, open the door for development of new strategies to detect or intercept the disease in its earliest stages.

Led by Humam Kadara, Ph.D., professor of Translational Molecular Pathology and Linghua Wang, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of Genomic Medicine, the team generated an atlas of around 250,000 normal and cancerous ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

Predicting extreme rainfall through novel spatial modeling

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

[Press-News.org] Molecular clusters on glial cells show they are more than our brain’s ‘glue’Underappreciated glia play central role in sensory response