(Press-News.org) Over the past two decades, the immune system has attracted increasing attention for its role in fighting cancer. As researchers have learned more and more about the cancer-immune system interplay, several antitumor immunotherapies have become FDA-approved and are now regularly used to treat multiple cancer types.

Yet despite these advances, much remains unknown about how the immune system fights cancer — and about immunity in general, said Martin LaFleur, a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Arlene Sharpe , chair of the Department of Immunology in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School.

CRISPR-based gene editing, in which scientists modify the genome using a tool developed just over a decade ago, has become a mainstay of biological discovery, providing relatively quick insight into the function of individual genes and targets for new therapies.

However, LaFleur said, this approach is not without challenges. Chief among them is that it is hard to modify immune cells without changing their biology, which hampers the ability to study immune cell behavior in its full complexity in a living organism.

Now, LaFleur, Sharpe, and their team have succeeded in bypassing this hurdle by deploying CRISPR in a new way to study the function of immune genes.

Their work, described in two papers — one in Nature Immunology and one in the Journal of Experimental Medicine — could eventually yield insights about cancer immunology as well as about other diseases driven by immune system dysfunction.

Harvard Medicine News spoke with LaFleur about what this advance means for the future of immunology research.

Harvard Medicine News: Let’s set the stage with a refresher on how CRISPR works.

LaFleur: Programmable CRISPR-based gene editing was developed in 2012 and became such a powerful tool for biologic research that its discoverers won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020.

The CRISPR gene-editing system uses an enzyme called Cas-9 that acts like a pair of molecular scissors that cuts both strands of DNA and in doing so disrupts or knocks out the function of a gene. To select the gene to knock out, this system uses a complementary piece of RNA that matches the gene and acts as a guide. It’s a very flexible approach for very quickly knocking out and studying the function of almost any gene you want.

HMNews: How is CRISPR used to understand the immune function of genes?

LaFleur: Immune cells interact with a lot of other cell types that can’t be modeled well in petri dishes, so we prefer immune studies to happen inside a living organism like a mouse — a far more reliable way to capture the complexity of cell-to-cell interactions as they occur in the body rather than in a lab dish. CRISPR editing inside the body is difficult, so immune cells typically need to come out and be modified using this tool in a petri dish. The edited cells are then put back into the body.

However, only certain immune cell types can be incorporated efficiently when transferred back into a mouse. Also, the actual process of manipulating immune cells in a dish can change their biology, so you may not be studying what you actually want to study once they’re removed from the body.

Also, CRISPR had been used only to turn off a single gene at a single time in immune cells. But our cells contain thousands of genes, so what if we want to knock out multiple genes in different cell types at different times in the same animal? This would provide greater insight into the complexities of genes and their interactions in immune cells over time.

HMNews: How does your new study address these challenges?

LaFleur: We decided to take a completely different approach for using CRISPR. Rather than directly modify the immune cells we’re interested in, we modified their precursors, the stem cells found in bone marrow that produce all immune cells. We removed those from mice and used CRISPR to knock out the genes we were interested in, and then replaced these stem cells in mice whose native bone marrow stem cells had been removed. We call this system CHimeric IMmune Editing, or CHIME.

In an earlier study, we used CHIME to knock out a gene called Ptpn2, which has shown some promise for cancer immunotherapy, one of the focuses of the Sharpe Lab. When we deleted that one gene in a subset of immune cells known as CD8+ T cells, they became better cancer fighters.

With our Nature Immunology study, we wanted to see if we could modify CHIME and make it both more precise and more versatile. We used it to knock out two genes at once in several different cell types; we deployed it to target genes specifically in a single cell type; we used CRISPR to disrupt genes in modified cells once they were already back inside the animal; and we also used it to knock out two different genes at different points in time.

We used different tactics, such as packaging multiple guide RNAs together and using a trick that disables genes only under certain circumstances, such as when mice receive a drug. We were able to demonstrate that each of these strategies is feasible.

HMNews: What is your ultimate goal with this research?

LaFleur: Our ultimate goal is to better understand the immune system, particularly in its capacity to fight cancer. We want to encourage strong anticancer immunity — meaning we want to optimize how immune cells fight tumors — but also want spare healthy cells and tissues from the immune attack. This requires a very nuanced calibration of the immune system and can be a tricky balance.

Moreover, the benefits could extend beyond cancer and be applied to many other diseases driven by the immune system, including autoimmune conditions.

HMNews: What are your next steps?

LaFleur: We just published a second paper that lays out a framework for the field in studies using CRISPR to screen immune gene function in living animals. Central to our framework is adding a genetic “barcode” to CRISPR-edited immune cells so we can track them as they multiply and spread within animals.

We’re hoping that this framework and CHIME will give researchers new tools to study immune cells in cancer or any other disease model of their choice, eventually leading to new immune-centered therapies.

END

Turbocharging CRISPR to understand how the immune system fights cancer

New gene-editing approach to study immune gene function could improve treatments for cancer, other diseases

2024-02-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

UBC Okanagan researchers create new compound to build space-age antennas

2024-02-29

In a first-of-its-kind development, UBC Okanagan researchers, in collaboration with Drexel University, have created a new compound that can be used to 3D print telecommunication antennas and other connectivity devices.

These 3D printed products, created by combining a two-dimensional compound called MXenes with a polymer, can be used as an alternative for metallic counterparts and can make a vast improvement in communication technology including elements such as antennas, waveguides and filters.

Waveguides are everywhere, yet most people don’t know what they are, says Dr. Mohammad Zarifi, a researcher in UBC Okanagan’s Microelectronics and Gigahertz ...

Study detects cognitive changes in older drivers using in-vehicle sensors

2024-02-29

An estimated 4 to 8 million older adults with mild cognitive impairment are currently driving in the United States, and one-third of them will develop dementia within five years. Individuals with progressive dementias are eventually unable to drive safely, yet many remain unaware of their cognitive decline.

Currently, screening and evaluation services for driving can only test a small number of individuals with cognitive concerns, missing many who need to know if they require treatment.

Nursing, engineering and neuropsychology researchers at Florida Atlantic University are testing and evaluating a readily and rapidly available, unobtrusive in-vehicle sensing ...

Terasaki Institute for Biomedical Innovation announces 2024 Paul Terasaki Award recipient

2024-02-29

(LOS ANGELES) – February 29, 2024 - The Terasaki Institute for Biomedical Innovation (TIBI) is pleased to announce their selection of Professor Nicholas A. Peppas of The University of Texas at Austin as the recipient of the 2024 Paul Terasaki Distinguished Scientist Innovation Award. The award will be presented at TIBI’s 2nd annual Terasaki Innovation Summit, to be held March 27-29, 2024, at the UCLA Meyer & Renee Luskin Conference Center.

The award was created in memory of Dr. Paul I. Terasaki, a pioneer in organ transplant research and innovation. It recognizes outstanding achievement in the field of biomedical ...

Terasaki Institute for Biomedical Innovation announces 2024 Hisako Terasaki Award recipients

2024-02-29

(LOS ANGELES) – February 29, 2024 - The Terasaki Institute for Biomedical Innovation (TIBI) is pleased to announce their selections of Assistant Professors Amir Manbachi of Johns Hopkins University and Ritu Raman of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as the recipients of the 2024 Hisako Terasaki Young Innovator Awards. The awards will be presented at TIBI’s 2nd annual Terasaki Innovation Summit, to be held March 27-29, 2024, at the UCLA Meyer & Renee Luskin Conference Center.

The award was created in memory of Hisako Terasaki, philanthropist, accomplished artist, and wife ...

Small dietary changes can cut your carbon footprint by 25%

2024-02-29

The latest Canada’s Food Guide presents a paradigm shift in nutrition advice, nixing traditional food groups, including meat and dairy, and stressing the importance of plant-based proteins. Yet, the full implications of replacing animal with plant protein foods in Canadians’ diets are unknown.

New research at McGill University in collaboration with the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine provides compelling evidence that partially substituting animal with plant protein foods can increase life expectancy and decrease greenhouse gas emissions. Importantly, ...

Uncertainty in measuring biodiversity change could hinder progress towards global targets for nature

2024-02-29

More than ever before, there is a growing interest in dedicating resources to stop the loss of biodiversity, as recently exemplified by the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) decided at COP15 in December 2022. The GBF focuses on understanding why biodiversity is declining and what actions are needed to reverse this trend. However, according to researchers at McGill University, implementing the plan is challenging because information about biodiversity changes is not evenly available everywhere, and is uncertain in many places.

With the available data, can the ...

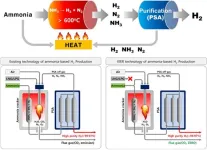

Zero emissions of carbon dioxide! Successful production of ammonia-based clean hydrogen

2024-02-29

Dr. Jung Unho's research team at the Hydrogen Research Department of the Korea Institute of Energy Research (KIER) has developed Korea's first clean hydrogen production technology. This technology is based on ammonia decomposition and does not use fossil fuels. The team's breakthrough could pave the way for a more sustainable and eco-friendly energy source. This allows for the production of high-purity hydrogen that meets international standards for hydrogen-powered vehicles, without the carbon dioxide emissions produced by using fossil fuels.

Ammonia, a compound of hydrogen and nitrogen, has a hydrogen storage density 1.7 times ...

Guiding future research on ‘extraordinary potential’ of next-generation solar cells

2024-02-29

Today’s commercial solar panels can convert about 15% to 20% of the sunlight they absorb into electrical energy — but they could be much more efficient, according to researchers at Soochow University. The next generation of solar cells has already demonstrated 26.1% efficiency, they said, but more specific research directions are needed to make such efficiency the standard and expand beyond it.

They published their review of the current state of research on high-efficiency perovskite solar cells and their recommendations for future work in Energy Materials and Devices on February 4.

“Metal halide perovskite ...

Urgent need for guidelines for the care of child victims of sexual abuse

2024-02-29

Only half of 34 surveyed European countries have national guidelines on how to provide clinical care and treatment to children who have experienced sexual abuse. This finding was revealed in a study led by researchers at Barnafrid, a national knowledge centre in the field of violence and other abuse against children, at Linköping University in Sweden. The consequences for the affected children can be severe, according to the researchers.

“Our findings suggest that children in Europe may not receive equal care. From a child rights perspective, this is unacceptable. ...

Overcoming barriers to conducting clinical trials in childhood rare disease research

2024-02-29

Using a novel methodology, researchers at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) are the first in paediatric research to use data from an international real-world cohort to overcome the barriers associated with conducting randomized clinical trials in children with rare diseases.

The gold standard for evaluating new therapeutics is through randomized clinical trials, where one group of individuals receives treatment while another does not. Unfortunately, conducting this type of clinical trial proves challenging for many rare conditions due to the limited number of individuals with the condition, making meaningful comparisons difficult. Additionally, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

How rice plants tell head from toe during early growth

Scientists design solar-responsive biochar that accelerates environmental cleanup

Construction of a localized immune niche via supramolecular hydrogel vaccine to elicit durable and enhanced immunity against infectious diseases

Deep learning-based discovery of tetrahydrocarbazoles as broad-spectrum antitumor agents and click-activated strategy for targeted cancer therapy

DHL-11, a novel prieurianin-type limonoid isolated from Munronia henryi, targeting IMPDH2 to inhibit triple-negative breast cancer

Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro inhibitors and RIPK1 inhibitors with synergistic antiviral efficacy in a mouse COVID-19 model

Neg-entropy is the true drug target for chronic diseases

Oxygen-boosted dual-section microneedle patch for enhanced drug penetration and improved photodynamic and anti-inflammatory therapy in psoriasis

Early TB treatment reduced deaths from sepsis among people with HIV

Palmitoylation of Tfr1 enhances platelet ferroptosis and liver injury in heat stroke

Structure-guided design of picomolar-level macrocyclic TRPC5 channel inhibitors with antidepressant activity

Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease: An evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines

New global review reveals integrating finance, technology, and governance is key to equitable climate action

New study reveals cyanobacteria may help spread antibiotic resistance in estuarine ecosystems

Around the world, children’s cooperative behaviors and norms converge toward community-specific norms in middle childhood, Boston College researchers report

How cultural norms shape childhood development

University of Phoenix research finds AI-integrated coursework strengthens student learning and career skills

Next generation genetics technology developed to counter the rise of antibiotic resistance

Ochsner Health hospitals named Best-in-State 2026

A new window into hemodialysis: How optical sensors could make treatment safer

High-dose therapy had lasting benefits for infants with stroke before or soon after birth

‘Energy efficiency’ key to mountain birds adapting to changing environmental conditions

Scientists now know why ovarian cancer spreads so rapidly in the abdomen

USF Health launches nation’s first fully integrated institute for voice, hearing and swallowing care and research

Why rethinking wellness could help students and teachers thrive

Seabirds ingest large quantities of pollutants, some of which have been banned for decades

When Earth’s magnetic field took its time flipping

Americans prefer to screen for cervical cancer in-clinic vs. at home

Rice lab to help develop bioprinted kidneys as part of ARPA-H PRINT program award

Researchers discover ABCA1 protein’s role in releasing molecular brakes on solid tumor immunotherapy

[Press-News.org] Turbocharging CRISPR to understand how the immune system fights cancerNew gene-editing approach to study immune gene function could improve treatments for cancer, other diseases