(Press-News.org) Climate change is disrupting the seasonal flow of rivers in the far northern latitudes of America, Russia and Europe and is posing a threat to water security and ecosystems, according to research published today.

A team of scientists led by the University of Leeds analysed historical data from river gauging stations across the globe and found that 21% of them showed significant alterations in the seasonal rise and fall in water levels.

The study used data-based reconstructions and state-of-the-art simulations to show that river flow is now far less likely to vary with the seasons in latitudes above 50°N than previously, and that this could be directly linked to changes to the climate caused by human activity.

Until now, evidence suggesting that climate change has had an impact on river flow seasonality has been limited to local studies or has failed to consider the impact of climate change brought about by humans explicitly.

In this study the team used monthly average river flow measurements from 10,120 gauging stations from 1965 to 2014.

For the first time ever, they were able to exclude direct human interventions such as reservoir management or water extraction, to show that widespread reduction in river flow seasonality was driven by climate change.

The results of the research, which was funded by the University of Leeds and the Southern University of Science and Technology in China are published today (29 February) in the journal Science.

Lead author, Hong Wang, a PhD researcher at the University of Leeds and the Southern University of Science and Technology in China, said: “Our research shows that rising air temperatures are fundamentally altering the natural patterns of river flow.

“The concerning aspect of this change is the observed weakening of river flow seasonality, and that this is as a direct consequence of historical human-induced emissions. This signals a sustained and considerable diminishment of river flow seasonality if air temperatures continue to rise.”

Human impact on river flow

Human activities are altering river flow patterns worldwide, both directly through flow regulations such as reservoirs, and indirectly through land use change and the impacts of climate change on air temperature, precipitation, soil moisture, and snowmelt.

Over two-thirds of the world’s rivers have already been altered by humans even without considering the indirect impacts of increases in greenhouse gases and aerosols.

River flow seasonality plays a critical role in the predicted cycle of floods and droughts. A weakening of these peaks and troughs can threaten water security and freshwater biodiversity. For example, a substantial portion of the early meltwater from snowpack depletion may quickly flow into oceans and therefore not be available for human use.

Weakening river flow seasonality - for example due to a reduction in spring and early summer river levels in snowmelt regions - can also have an impact downstream on riverbank vegetation and organisms living in the river itself.

Gauging the seasonal flow

In northern North America, the researchers found that 40% of the 119 stations observed showed a significant decrease in river flow seasonality. Similar results were also observed in sSouthern Siberia with 32% of stations showing a significant decrease.

There was a comparable pattern in Europe, with 19% of the river gauging stations experiencing a significant decrease - mainly in northern Europe, western Russia and the European Alps.

In addition, regions in the contiguous United States (the lower 48 states in North America, including the District of Columbia) showed predominantly decreasing trends of river flow seasonality overall, except for rivers in the Rocky Mountains and Florida.

In central North America, the research showed significant decreasing river flow seasonality trends in 18% of the stations.

By contrast, the researchers found a significant increase in river flow seasonality in 25% of the gauging stations in southeast Brazil, showing that changes to the water cycle are having a different impact in some parts of the world.

Dr Megan Klaar, an Associate Professor in the University of Leeds School of Geography and a member of water@leeds, co-authored the research. She said: “The highs and lows of river flow during the different seasons provide vital cues for the species living in the water.

“For example, a lot of fish use particular increases in the water as a cue to run to their breeding areas upstream or towards the sea. If they don’t have those cues, they won’t be able to spawn.”

The research concludes that there is a need to accelerate climate adaptation efforts to safeguard freshwater ecosystems by managing flows to try to recreate some of the natural systems and processes that are being lost.

Professor Joseph Holden, the Director of water@leeds and who supervised Hong Wang’s research, added: “A lot of concern is based upon what climate change will do in the future but our research signals that it’s happening now and that increases in air temperature are driving huge changes in river flow.

“We should be very concerned about what the future holds given accelerating climate change and begin to think about mitigation strategies and adaptation planning to alleviate the future weakening of seasonal river flow, particularly in locations such as western Russia, Scandinavia, and Canada.”

Ends

Notes to editors

Anthropogenic climate change has influenced global river flow seasonality is published today (29 February) in the journal Science

The DOI is 10.1126/science.adi9501

Pictures and illustrations available here

Photo of alpine river in Zinal, Switzerland: Please credit Yoal Desurmont

Illustration 1: Credit Myriam Wares

Email: contact@myriamwares.com

The rapid rise in air temperature, driven by human-induced emissions, is diminishing the seasonal variations in river flow. This weakening pattern of river flow seasonality has the potential to impact riparian vegetation, the life cycles of freshwater biota, and water security.

Illustration 2: Credit Elena Galofaro Bansh

Email: elena@elenabanshart.com

The rapid rise in air temperature, driven by human-induced emissions, is diminishing the seasonal variations in river flow. The homogenized monthly distribution of river flow throughout the year has the potential to impact freshwater ecosystems and water security.

For media enquiries or interview requests, please contact Kersti Mitchell via k.mitchell@leeds.ac.uk

Other institutions involved in the research were:

School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, China

North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power, Zhengzhou, China

Henan Provincial Key Lab of Hydrosphere and Watershed Water Security, North China

University of Water Resources and Electric Power, Zhengzhou, China

Institute for Atmospheric and Climate Science, ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland

University of Leeds

The University of Leeds is one of the largest higher education institutions in the UK, with more than 39,000 students from more than 137 different countries. We are renowned globally for the quality of our teaching and research.

We are a values-driven university, and we harness our expertise in research and education to help shape a better future for humanity, working through collaboration to tackle inequalities, achieve societal impact and drive change.

The University is a member of the Russell Group of research-intensive universities, and is a major partner in the Alan Turing, Rosalind Franklin and Royce Institutes www.leeds.ac.uk

Follow University of Leeds or tag us in to coverage: Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn | Instagram

END

Climate change disrupts seasonal flow of rivers

Climate change is disrupting the seasonal flow of rivers in the far northern latitudes of America, Russia and Europe and is posing a threat to water security and ecosystems, according to research published today.

2024-02-29

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers reveal mechanism of how the brain forms a map of the environment

2024-02-29

When you walk into your kitchen in the morning, you easily orient yourself. To make coffee, you approach a specific location. Maybe you step into the pantry to grab a quick breakfast and then head to your car to drive to your workplace.

How these apparently simple tasks happen is of major interest to neuroscientists at Baylor College of Medicine, Stanford University and collaborating institutions. Their work, published in the journal Science, has significantly improved our understanding of how this occurs by revealing a mechanism at the brain cell level that mediates how an animal moves about in the environment.

“It’s been known that animals and people can find their ...

Improving energy security with policies focused on demand-side solutions

2024-02-29

Governments typically rely on policies focused on energy supply to enhance energy security, ignoring demand-side options. Current indicators and indexes that measure energy security focus mostly on energy supply. This aligns with the International Energy Agency’s view, which defines energy security only in terms of security of supply. However, this approach does not fully capture the extent of vulnerability for states, businesses, and individuals during an energy crisis.

“Energy security assessments also need to reflect how vulnerable countries, firms, and households are to energy ...

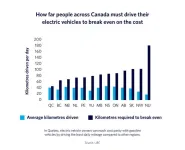

Driving an electric car is cheaper in some parts of Canada than others

2024-02-29

Electric vehicles are a critical part of Canada’s climate strategy, but a new University of British Columbia study highlights how it’s cheaper in some regions than others to drive electric—making it more challenging for certain households to make the switch.

Location, location, location

The researchers analyzed how far people need to drive their electric car to break even on the cost, factoring in the impacts of tax rebates and tax rates, charging costs, typical distance households travel in a region, and electricity ...

Emergency atmospheric geoengineering wouldn’t save the oceans

2024-02-29

WASHINGTON — Climate change is heating the oceans, altering currents and circulation patterns responsible for regulating climate on a global scale. If temperatures dropped, some of that damage could theoretically be undone. But employing “emergency” atmospheric geoengineering later this century in the face of continuous high carbon emissions would not be able to reverse changes to ocean currents, a new study finds. This would critically curtail the intervention’s potential effectiveness ...

New model of key brain tumor feature could help scientists understand how to develop new treatments

2024-02-29

ANN ARBOR, Michigan — Researchers at the University of Michigan Health Rogel Cancer Center are exploiting a unique biological feature of glioblastoma to gain a better understanding of how this puzzling brain cancer develops and how to target new treatments against it.

The team, led by senior author Pedro Lowenstein, M.D., Ph.D., Richard Schneider Collegiate Professor of Neurosurgery at Michigan Medicine, had previously identified oncostreams as a key feature in glioblastoma development and in more aggressive disease. These highly active, elongated, spindle-like cells ...

Study: Mutations in hereditary Alzheimer’s disease damage neurons without ‘usual suspect’ amyloid plaques

2024-02-29

LAWRENCE — A University of Kansas study of rare gene mutations that cause hereditary Alzheimer's disease shows these mutations disrupt production of a small sticky protein called amyloid.

Plaques composed of amyloid are notoriously found in the brain in Alzheimer’s disease and have long been considered responsible for the inexorable loss of neurons and cognitive decline. Using a model species of worm called C. elegans that’s often used in labs to study diseases at the molecular level, the research team came to the surprising conclusion that the stalled process of amyloid production — not the amyloid itself — can trigger loss of critical ...

Rice lab finds better way to handle hard-to-recycle material

2024-02-29

HOUSTON – (Feb. 29, 2024) – Glass fiber-reinforced plastic (GFRP), a strong and durable composite material, is widely used in everything from aircraft parts to windmill blades. Yet the very qualities that make it robust enough to be used in so many different applications make it difficult to dispose of ⎯ consequently, most GFRP waste is buried in a landfill once it reaches its end of life.

According to a study published in Nature Sustainability, Rice University researchers and collaborators have developed a new, energy-efficient upcycling method to transform glass fiber-reinforced plastic ...

Ice shell thickness reveals water temperature on ocean worlds

2024-02-29

ITHACA, N.Y. – Cornell University astrobiologists have devised a novel way to determine ocean temperatures of distant worlds based on the thickness of their ice shells, effectively conducting oceanography from space.

Available data showing ice thickness variation already allows a prediction for the upper ocean of Enceladus, a moon of Saturn, and a NASA mission’s planned orbital survey of Europa’s ice shell should do the same for the much larger Jovian moon, enhancing the mission’s findings about whether it could support ...

Garrett Isaac Neubauer Center for Cardiovascular Innovation launches at Columbia

2024-02-29

NEW YORK, NY (February 29, 2024)--Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons (VP&S) today announced the launch of a new center for pediatric cardiovascular innovation, made possible through a visionary gift by Lawrence Neubauer. The mission of the new center is to improve outcomes for patients through groundbreaking research and care and to define the next cures for and future practice in congenital heart disease (CHD)—here and across the world.

In recognition of the transformative generosity of Lawrence Neubauer, the center will be named the Garrett Isaac Neubauer Center for Cardiovascular ...

MSU co-authored study: 10 insights to reduce vaccine hesitancy on social media

2024-02-29

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Effective population level vaccination campaigns are fundamental to public health. Countercampaigns, which are as old as the first vaccines, can disrupt uptake and threaten public health globally.

Even before March 2020, vaccine hesitancy was directly linked to misinformation — false, inaccurate information promoted as factual — on social media. Once COVID-19 reached pandemic status, social media was acknowledged as the epicenter of information leading to vaccine hesitancy, which the World Health Organization, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

[Press-News.org] Climate change disrupts seasonal flow of riversClimate change is disrupting the seasonal flow of rivers in the far northern latitudes of America, Russia and Europe and is posing a threat to water security and ecosystems, according to research published today.