(Press-News.org) This is a natural 'anti-failure' mechanism in the DNA copying process, hitherto unknown.

The DNA molecule is copied each time a cell divides. If, instead of being copied once, the DNA is copied several times, i.e. tripled or even quadrupled, the likelihood of cancer increases..

The new discovered anti-failure system relies on a protein called RAD51 to prevent DNA that has already been copied from being copied again.

Every time a cell divides, its DNA is duplicated so that the two daughter cells have the same genetic material as their parent. This means that millions of times a day a biochemical wonder takes place in the body: the copying of the DNA molecule. It is a high-precision job carried out by specific proteins and includes systems to protect against potential errors that could lead to diseases such as cancer.

One of these anti-failure systems has just been discovered by researchers in the DNA Replication Group at the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), led by Juan Méndez. It is based on a protein that ensures that DNA is copied only once, as it should be, and not twice or more.

When a region of DNA is over-replicated, breaks are created in the molecule, and the likelihood of a cancer-related gene being over-expressed increases (if it is in the over-replicated region); its negative impact on the functioning of the cell would then be greater and it could be the start of a cancer.

Therefore, avoiding excess replication “prevents DNA damage and reduces the chances of oncogenes being amplified,” says Méndez.

Copying a sequence of 3 billion parts without errors

The DNA molecule has a double-helix structure. To be copied, the two strands of the helix are first separated and each one serves as a template for the replication machinery to build two new double helices. Completing the process takes hours. In tissues that regenerate very frequently, such as the skin or intestines, cells replicate (and copy DNA) almost continuously.

It is not a simple process. A human DNA molecule has 3 billion chemical pieces, the bases—the famous letters A, T, C, G. The order in which these letters are arranged makes up the genetic information, i.e. the instructions that tell the cell to make this or that protein at any given moment.

If the instructions are wrong—for example, if there are mutations—disease can occur. Therefore, DNA copying is a critical process for the organism, which has developed several molecular mechanisms to avoid errors. The one that CNIO researchers have now discovered involves the RAD51 protein. Its mission, in this context, is to prevent DNA fragments that have already been copied once from being copied again.

Copying starts in thousands of places at once

DNA copying begins at thousands of sites simultaneously, which are called origins in the jargon. The proteins responsible for copying attach themselves to these origins and start working, acting like micro-machines.

An initial system for controlling excess replication was already known, which prevents origins from being activated more than once. However, if a second copying process is mistakenly started, the newly discovered anti-failure mechanism comes into play, based on RAD51.

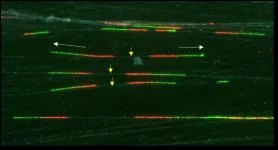

Researchers at CNIO observed that RAD51 temporarily binds to the newly synthesized DNA. If the copying process is inadvertently reactivated, its presence on the new DNA (which now serves as a template for copying) becomes a physical impediment: the copying machinery cannot continue to advance.

A second brake on re-replication

“We observed that RAD51 acts as a second brake on DNA re-replication,” says Sergio Muñoz, first author of the study. In this way, “RAD51 prevents genomic duplications that could arise from re-activated origins.”

In their publication in The EMBO Journal, the authors write that “DNA re-replication could fuel carcinogenesis by promoting aneuploidy [an incorrect number of chromosomes in the cell] and the formation of heterogeneous cell populations that enhance the adaptability of tumor cells.”

The protective role of RAD51 may be particularly important in pre-tumoral lesions, where there is an increased risk of over-replication.

Researchers from the University of Zurich also participated in the study.

END

Newly discovered protein prevents DNA triplication

2024-03-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

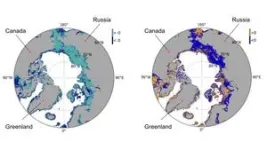

Less ice in the arctic ocean has complex effects on marine ecosystems and ocean productivity

2024-03-04

Over the past 25 years, the amount of summer Arctic sea ice has diminished by more than 1 million square kilometers. As a result, vast areas of the Arctic Ocean are now, on average, ice free in summer. Scientists are closely monitoring how this impacts sunlight availability and marine ecosystems in the far north.

“Many questions arise when such large areas become ice-free and can receive sunlight. A prevailing paradigm suggests that the Arctic Ocean is rapidly becoming more productive as sunlight becomes ...

Antarctica’s coasts are becoming less icy

2024-03-04

EMBARGOED UNTIL MARCH 4, 2024 AT 3:00PM U.S EASTERN TIME

An increase in pockets of open water in Antarctica’s sea ice (polynyas) may mean coastal plants and animals could one day establish on the continent, University of Otago-led research suggests.

The research, published in the prestigious international journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, aimed at understanding where open water might allow coastal species to settle in the future.

Led by Research Fellow Dr Grant Duffy from Otago’s Department ...

New research shows migrating animals learn by experience

2024-03-04

THIS RELEASE IS EMBARGOED UNTIL MARCH 4, 2024, at 3:00 PM U.S. EASTERN TIME.

Research led by scientists from University of Wyoming and Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior shows that migrating animals refine their behavior as they get older, suggesting that experiential learning is an important part of successful migration.

While genetics and social behavior are important factors shaping animal migrations, information gained through individual experience also appears to help shape migratory movements, says a research team led by Ellen Aikens. Aikens, ...

Modeling the origins of life: New evidence for an “RNA World”

2024-03-04

LA JOLLA (March 4, 2024)—Charles Darwin described evolution as "descent with modification." Genetic information in the form of DNA sequences is copied and passed down from one generation to the next. But this process must also be somewhat flexible, allowing slight variations of genes to arise over time and introduce new traits into the population.

But how did all of this begin? In the origins of life, long before cells and proteins and DNA, could a similar sort of evolution have taken place on a simpler scale? ...

Scientists put forth a smarter way to protect a smarter grid

2024-03-04

RICHLAND, Wash.—There’s a down side to “smart” devices: They can be hacked.

That makes the electric grid, increasingly chock full of devices that interact with one another and make critical decisions, vulnerable to bad actors who might try to turn off the power, damage the system or worse.

But smart devices are a big part of our future as the world moves more toward renewable energy and the many new devices to manage it. Already, such tools play a big role in keeping the power humming. The portion of the grid owned by ...

An evolutionary mystery 125 million years in the making

2024-03-04

Plant genomics has come a long way since Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) helped sequence the first plant genome. But engineering the perfect crop is still, in many ways, a game of chance. Making the same DNA mutation in two different plants doesn’t always give us the crop traits we want. The question is why not? CSHL plant biologists just dug up a reason.

CSHL Professor and HHMI Investigator Zachary Lippman and his team discovered that tomato and Arabidopsis thaliana plants can use very different regulatory systems to control the same exact ...

Data science approach to identifying thermal conductivity-related structural factors in amorphous materials

2024-03-04

1. Using data science techniques, a NIMS–Tohoku University research team has discovered that different thermal conductivities exhibited by an amorphous material with the same composition are attributable to the sizes of atomic rings in its atomic structure. This is one of the first studies demonstrating that the structural features of amorphous materials can be correlated with their physical properties.

2. It is already feasible to synthesize amorphous materials with the same compositions but different thermal conductivities. However, the structural factors responsible for differences in thermal conductivity had yet to be identified due to a lack of appropriate analytical ...

Deciphering the male breast cancer genome

2024-03-04

Male breast cancer has distinct alterations in the tumor genome that may suggest potential treatment targets, according to a study by Weill Cornell Medicine investigators. They have conducted the first whole genome sequencing analysis of male breast cancer, which looked at the complete DNA landscape of tumor samples from 10 patients.

This is an important step in viewing breast cancer in men, which represents less than 1 percent of all breast cancer cases each year, as a unique disease. Though most research has focused on women with breast cancer, the incidence in men has increased at a much faster rate than in women over the last 40 years. Also, ...

Detection of suicide-related emergencies among children using real-world clinical data: A free webinar from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation

2024-03-04

According to the CDC, the suicide rate among young people ages 10‒24 increased 62% from 2007 through 2021. The CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Summary reports that in 2021, 22% of high school students seriously considered attempting suicide during the year and 18% made a suicide plan. These statistics indicate a mental health crisis facing our youth. How can we identify children in crisis? Who is being missed?

The Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (BBRF) is hosting a free webinar, “Detection of Suicide-Related Emergencies Among ...

Editor-in-Chief of Sustainability and Climate Change Madhavi Venkatesan named USA TODAY Woman of the Year for Massachusetts for leading plastic bottle ban efforts

2024-03-04

Madhavi Venkatesan, PhD, Editor-in-Chief of the peer-reviewed journal Sustainability and Climate Change and founder of Sustainable Practices, has been named USA TODAY Woman of the Year for the state of Massachusetts in recognition of her outstanding efforts to eliminate single-use plastic bottles across Cape Cod and the Islands.

With economics and sustainability at the forefront, Venkatesan established Sustainable Practices in 2016, aiming to address pressing environmental issues through innovative solutions. Since then, she and her nonprofit team have spearheaded ...