(Press-News.org) Getting climate models to mimic real-time observations when it comes to warming is critical – small discrepancies can lead to misunderstandings about the rate of global warming as the climate changes. A new study from North Carolina State University and Duke University finds that when modeling warming trends in the Pacific Ocean, there is still a missing piece to the modeling puzzle: the effect of wind on ocean currents in the equatorial Pacific.

“The Pacific Ocean can act like a thermostat for the global climate,” says Sarah Larson, assistant professor of marine, earth and atmospheric sciences at NC State and coauthor of the study. “If the Pacific warms quickly, for example, it can accelerate warming globally. Similarly, if it warms at a slower pace, this can slow down our rate of global warming.”

Over the last several decades, scientists have noted a complicated warming pattern in the tropical Pacific, with eastern and western Pacific waters warming while a slight cooling effect was seen in the central Pacific close to the equator. When scientists attempted to model this warming pattern by feeding historical data into the models, they found that current models could not reproduce the observed pattern.

“These models simulate the atmosphere and the ocean’s response to what we call ‘external forcing,’ which are things like greenhouse gases and aerosols in the atmosphere,” Larson says. “However, we think models don’t accurately simulate the tropical Pacific Ocean’s response.

“We’re trying to figure out what physical processes in the models we can attribute this discrepancy to, so we looked at wind,” Larson says. “If wind is important to ocean currents and ocean currents move heat around, then we could be getting the wind-driven portion of warming wrong in the models.”

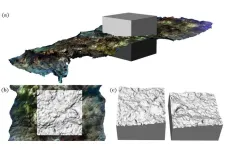

The researchers ran two different models that encompassed the same time period – one in which winds changed in response to external forcing, and one ‘decoupled’ model, in which the winds replicated those prior to the industrial revolution and did not change in response to forcing.

In the model where winds changed, warming trends followed those observed, apart from the cooling along the equator. In the decoupled model, these patterns did not appear.

“We removed wind changes from the decoupled model to better understand its effects on how the tropical Pacific climate evolved,” Larson says.

“Let’s take Galápagos Islands in the eastern Pacific as an example,” says Shineng Hu, assistant professor of earth and climate science at Duke University and study co-author. “The ocean water to the north of the equator is warmer than the equatorial water there. We found that the human-induced warming triggered westerly winds to the north of Galápagos Islands, which in turn transported the warm water beneath southward. That is what we think acts as a key process through which winds affect the tropical Pacific warming pattern.”

“What this tells us is that how the winds react to human-induced forcing like greenhouse gases is incredibly important to determining how quickly the tropical Pacific warms and so far, the winds are changing in ways the models didn’t anticipate,” Larson says. “We know that wind is the key, but this finding points to an urgent need to better simulate equatorial oceanic processes and thermal structures to create more accurate models.”

The work appears in Nature Communications and was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant AGS-1951713). Shuo Fu, a graduate student visiting Hu’s lab at Duke from Ocean University of China, is first author. Xiao-Tong Zheng from Ocean University of China, Yiqun Tian of Duke and Kay McMonigal of NC State also contributed to the work.

-peake-

Note to editors: An abstract follows.

“Historical changes in wind-driven ocean circulation drive pattern of Pacific warming”

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-45677-2

Authors: Shuo Fu, Xiao-Tong Zheng, Ocean University of China; Shineng Hu, Yiqun Tian, Duke University; Kay McMonigal, Sarah Larson, North Carolina State University

Published: Feb. 26, 2024 in Nature Communications

Abstract:

The tropical Pacific warming pattern since the 1950s exhibits two warming centers in the western Pacific (WP) and eastern Pacific (EP), encompassing an equatorial central Pacific (CP) cooling and a hemispheric asymmetry in the subtropical EP. The underlying mechanisms of this warming pattern remain debated. Here, we conduct ocean heat decompositions of two coupled model large ensembles to unfold the role of wind-driven ocean circulation. When wind changes are suppressed, historical radiative forcing induces a subtropical northeastern Pacific warming, thus causing a hemispheric asymmetry that extends toward the tropical WP. The tropical EP warming is instead induced by the cross-equatorial winds associated with the hemispheric asymmetry, and its driving mechanism is southward warm Ekman advection due to the off-equatorial westerly wind anomalies around 5°N, not vertical thermocline adjustment. Climate models fail to capture the observed CP cooling, suggesting an urgent need to better simulate equatorial oceanic processes and thermal structures.

END

Replacing long-acting with immediate-release opioids after total knee replacement surgery resulted in comparable pain management but less nausea-medication usage and less need for residential rehabilitation after hospital discharge.

The results of this small study, a Rutgers Nursing doctoral program project for lead author Anoush Kalachian, support a broader trend toward better management of prescription opioids – which directly resulted in the deaths of nearly 17,000 Americans in 2021 and can spur the use of illegal opioids.

Widespread changes in opioid use patterns for knee replacement patients would have a significant impact on ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Combining two treatments could be a promising option for people, especially military veterans, whose lives are negatively affected by post-traumatic stress disorder, a new study shows.

In a clinical trial conducted among U.S. military veterans at the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center, participants who received brain stimulation with a low electrical current during sessions of virtual reality exposure reported a significant reduction in PTSD symptom severity. The results ...

The Ecological Society of America (ESA) presents a roundup of six research articles published in March issues across its six esteemed journals. Widely recognized for fostering innovation and advancing ecological knowledge, ESA's journals consistently feature innovative and impactful studies. The compilation of papers delves into beetle energetics, the interplay between wildfire and climate change, salamander conservation and more, showcasing the Society's commitment to promoting cutting-edge research ...

The support for the hypothesis of Spinosaurus as an aquatic pursuit predator may have had fundamental flaws, according to Nathan Myhrvold of Intellectual Ventures, US and colleagues, in a study published March 6, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE.

Paleontologists generally agree that the famous Spinosaurus was a fish-eater, but exactly how these dinosaurs caught their prey is the subject of lively debate, with some researchers suggesting that they hunted on the shore, some that they waded or swam in the shallows, and others that they were aquatic pursuit predators. One recent study provided support for the latter hypothesis using a fairly new ...

Certain factors associated with developing age-related hearing loss differ by sex, including weight, smoking behavior, and hormone exposure, according to a study published on March 6, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Dong Woo Nam from Chungbuk National University Hospital, South Korea, and colleagues.

Age-related hearing loss (ARHL), slowly-advancing difficulty in hearing high-frequency sounds, makes spoken communication more challenging, often leading to loneliness and depression. Roughly 1 in 5 people around the world suffer ...

Higher BMI is significantly associated with worse mental health, especially in women, per study of middle-aged and older adults which adjusted for lifestyle and demographic factors

###

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0299029

Article Title: Associations between adiposity measures and depression and well-being scores: A cross-sectional analysis of middle- to older-aged adults

Author Countries: Ireland

Funding: This research was funded by the Irish Health Research Board, grant number: HRC/2007/13. The funder had no role in the ...

An injectable hydrogel can mitigate damage to the right ventricle of the heart with chronic pressure overload, according to a new study published March 6 in Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Basic to Translational Science.

The study, by a research team from the University of California San Diego, Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University, was conducted in rodents. In 2019, this same hydrogel was shown to be safe in humans through an FDA-approved Phase 1 trial in people who suffered a heart attack. As a result of the new preclinical ...

For years, controversy has swirled around how a Cretaceous-era, sail-backed dinosaur—the giant Spinosaurus aegyptiacus—hunted its prey. Spinosaurus was among the largest predators ever to prowl the Earth and one of the most adapted to water, but was it an aquatic denizen of the seas, diving deep to chase down its meals, or a semiaquatic wader that snatched prey from the shallows close to shore?

A new analysis led by paleontologists from the University of Chicago reexamines the density ...

Greg Rouse, a marine biologist at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and other researchers have discovered a new species of deep-sea worm living near a methane seep some 50 kilometers (30 miles) off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica. Rouse, curator of the Scripps Benthic Invertebrate Collection, co-authored a study describing the new species in the journal PLOS ONE that was published on March 6.

The worm, named Pectinereis strickrotti, has an elongated body that is flanked by a row of feathery, gill-tipped appendages called ...

The high-tech double-barrel nanopipette, developed by University of Leeds scientists, and applied to the global medical challenge of cancer, has - for the first time - enabled researchers to see how individual living cancer cells react to treatment and change over time – providing vital understanding that could help doctors develop more effective cancer medication.

The tool has two nanoscopic needles, meaning it can simultaneously inject and extract a sample from the same cell, expanding its potential uses. And the platform’s high level of semi-automation has sped ...