(Press-News.org) EVANSTON, Ill. — Researchers led by Northwestern University and Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have developed a new, first-of-its-kind sticker that enables clinicians to monitor the health of patients’ organs and deep tissues with a simple ultrasound device.

When attached to an organ, the soft, tiny sticker changes in shape in response to the body’s changing pH levels, which can serve as an early warning sign for post-surgery complications such as anastomotic leaks. Clinicians then can view these shape changes in real time through ultrasound imaging.

Currently, no existing methods can reliably and non-invasively detect anastomotic leaks — a life-threatening condition that occurs when gastrointestinal fluids escape the digestive system. By revealing the leakage of these fluids with high sensitivity and high specificity, the non-invasive sticker can enable earlier interventions than previously possible. Then, when the patient has fully recovered, the biocompatible, bioresorbable sticker simply dissolves away — bypassing the need for surgical extraction.

The study will be published on Friday (March 8) in the journal Science. The paper outlines evaluations across small and large animal models to validate three different types of stickers made of hydrogel materials tailored for the ability to detect anastomotic leaks from the stomach, the small intestine and the pancreas.

“These leaks can arise from subtle perforations in the tissue, often as imperceptible gaps between two sides of a surgical incision,” said Northwestern’s John A. Rogers, who led device development with postdoctoral fellow Jiaqi Liu. “These types of defects cannot be seen directly with ultrasound imaging tools. They also escape detection by

even the most sophisticated CT and MRI scans. We developed an engineering approach and a set of advanced materials to address this unmet need in patient monitoring. The technology has the potential to eliminate risks, reduce costs and expand accessibility to rapid, non-invasive assessments for improved patient outcomes.”

“Right now, there is no good way whatsoever to detect these kinds of leaks,” said gastrointestinal surgeon Dr. Chet Hammill, who led the clinical evaluation and animal model studies at Washington University with collaborator Dr. Matthew MacEwan, an assistant professor of neurosurgery. “The majority of operations in the abdomen — when you have to remove something and sew it back together — carry a risk of leaking. We can’t fully prevent those complications, but maybe we can catch them earlier to minimize harm. Even if we could detect a leak 24- or 48-hours earlier, we could catch complications before the patient becomes really sick. This new technology has potential to completely change the way we monitor patients after surgery.”

A bioelectronics pioneer, Rogers is the Louis Simpson and Kimberly Querrey Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Biomedical Engineering and Neurological Surgery, with appointments at the McCormick School of Engineering and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. He also directs the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics. At the time of the research, Hammill was an associate professor of surgery at Washington University. Rogers, Hammill and MacEwan co-led the research with Heling Wang, an associate professor at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

The importance of being early

All gastrointestinal surgeries carry the risk of anastomotic leaks. If the leak is not detected early enough, the patient has a 30% chance of spending up to six months in the hospital and a 20% chance of dying, according to Hammill. For patients recovering from pancreatic surgery, the risks are even higher. Hammill says a staggering 40-60% of patients suffer complications after pancreas-related surgeries.

The biggest problem is there’s no way to predict who will develop such complications. And, by the time the patient is experiencing symptoms, they already are incredibly ill.

“Patients might have some vague symptoms associated with the leak,” Hammill said. “But they have just gone through big surgery, so it’s hard to know if the symptoms are abnormal. If we can catch it early, then we can drain the fluid. If we catch it later, the patient can get sepsis and end up in the ICU. For patients with pancreatic cancer, they might only have six months to live as it is. Now, they are spending half that time in the hospital.”

In search of improved outcomes for his patients, Hammill contacted Rogers, whose laboratory specializes in developing engineering solutions to address health challenges. Rogers’ team had already developed a suite of bioresorbable electronic devices to serve as temporary implants, including dissolving pacemakers, nerve stimulators and implantable painkillers.

The bioresorbable systems piqued Hammill’s interest. The greatest odds of developing an anastomotic leak occur either three days or two weeks after surgery.

“We like to monitor patients for complications for about 30 days,” Hammill said. “Having a device that lasts a month and then disappears sounded ideal.”

Enhancing ultrasound

Instead of developing new imaging systems, Rogers speculated that his team might be able to enhance current imaging methods — allowing them to “see” features that otherwise would be invisible. Ultrasound technology already has many advantages: it’s inexpensive, readily available, does not require cumbersome equipment and does not expose patients to radiation or other risks.

But, of course, there is a major drawback. Ultrasound technology — which uses sound waves to determine the position, shape and structure of organs — cannot reliably differentiate between various bodily fluids. Blood and gastric fluid, for example, appear the same.

“The acoustic properties of the leaking fluids are very similar to those of naturally occurring biofluids and surrounding tissues,” Rogers said. “The clinical need, however, demands chemical specificity, beyond the scope of fundamental mechanisms that create contrast in ultrasound images.”

Ultimately, Rogers’ team devised an approach to overcome this limitation by using tiny sensor devices designed to be readable by ultrasound imaging. Specifically, they created a small, tissue-adhesive sticker out of a flexible, chemically responsive, soft hydrogel material. Then, they embedded tiny, paper-thin metal disks into the thin layers of this hydrogel. When the sticker encounters acidic fluids, such as stomach acid, it swells. When the sticker encounters caustic fluids, such as pancreatic fluids, it contracts.

Making the invisible visible

As the hydrogel swells or shrinks in response to changing pH, the metal disks either move apart or closer together, respectively. Then, the ultrasound can view these subtle changes in placement.

“Because the acoustic properties of the metal disks are much different than those of the surrounding tissue, they provide very strong contrast in ultrasound images,” Rogers said. “In this way, we can essentially ‘tag’ an organ for monitoring.” Because the need for monitoring extends only during a postsurgical recovery, Rogers team designed these stickers with bioresorbable materials. They simply disappear naturally and harmlessly in the body after they are no longer needed.

Computational collaborator Yonggang Huang, the Jan and Marcia Achenbach Professorship in Mechanical Engineering and professor of civil and environmental engineering at McCormick, used acoustic and mechanical simulation techniques to help guide optimized choices in materials and device layouts to ensure high visibility in ultrasound images, even for stickers located at deep positions within the body.

“CT and MRI scans just take a picture,” Hammill added. “The fluid might show up in a CT image, but there’s always fluid collections after surgery. We don’t know if it’s actually a leak or normal abdominal fluid. The information that we get from the new patch is much, much more valuable. If we can see that the pH is altered, then we know that something isn’t right.”

Rogers team constructed stickers of varying sizes. The largest measures 12 millimeters in diameter, while the smallest is just 4 millimeters in diameter. Considering that the metal disks are each 1 millimeter or smaller, Rogers realized that it might be difficult for radiologists to assess the images manually. To overcome this challenge, his team also developed software that can automatically analyze the images to detect with high accuracy any relative movement of the disks.

Improving quality of life

To evaluate the efficacy of the new sticker, Hammill’s team tested it in both small and large animal models. In the studies, ultrasound imaging consistently detected changes in the shape-shifting sticker — even when it was 10 centimeters deep inside of tissues. When exposed to fluids with abnormally high or low pH levels, the sticker altered its shape within minutes.

Rogers and Hammill imagine that the device could be implanted at the end of a surgical procedure. Or, because it’s small and flexible, the device also fits (rolled up) inside a syringe, which clinicians can use to inject the tag into the body.

“These tags are so small and thin and soft that surgeons can easily place collections of them at different locations,” Rogers said. “For example, if an incision extends by a few centimeters in length, an array of these tags can be placed along the length of the site to develop a map of pH for precisely locating the position of the leak.”

“It’s obviously an early prototype, but I can envision the final product where, at the end of surgery, you just place these little patches for monitoring,” Hammill said. “It does its job and then completely disappears. This could have a huge impact on patients, their recovery time and, ultimately, their quality of life.”

Next, Rogers and his team are exploring similar tags that could detect internal bleeding or temperature changes. “Detecting changes in pH is a good starting point,” Rogerssaid. “But this platform can extend to other types of applications by use of hydrogels that respond to other changes in local chemistry, or to temperature or other properties of clinical relevance.”

The study, “Bioresorbable shape-adaptive structures for ultrasonic monitoring of deep-tissue homeostasis,” was supported by the National Science Foundation, the National Cancer Institute and the Querrey-Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics.

END

Shape-shifting ultrasound stickers detect post-surgical complications

First-of-its-kind device ‘tags’ an organ to monitor abnormal, life-threatening fluid leaks

2024-03-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The Malaria parasite generates genetic diversity using an evolutionary ‘copy-paste’ tactic

2024-03-07

By dissecting the genetic diversity of the most deadly human malaria parasite – Plasmodium falciparum – researchers at EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) have identified a mechanism of ‘copy-paste’ genetics that increases the genetic diversity of the parasite at accelerated time scales. This helps solve a long-standing mystery regarding why the parasite displays hotspots of genetic diversity in an otherwise unremarkable genetic landscape.

Malaria is most commonly transmitted through the bites of female Anopheles mosquitoes infected with P. falciparum. The latest world malaria report ...

Loss of nature costs more than previously estimated

2024-03-07

Researchers propose that governments apply a new method for calculating the benefits that arise from conserving biodiversity and nature for future generations.

The method can be used by governments in cost-benefit analyses for public infrastructure projects, in which the loss of animal and plant species and ‘ecosystem services’ – such as filtering air or water, pollinating crops or the recreational value of a space – are converted into a current monetary value.

This process is designed to make biodiversity loss and the benefits of nature conservation more visible in political decision-making.

However, the international research team ...

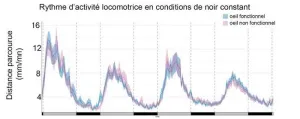

Lack of functional eyes does not affect biological clock in zebrafish

2024-03-07

Functional eyes are not required for a working circadian clock in zebrafish, as a research team1 including CNRS scientists has now shown.

Though it is understood that the eye plays a key role in mammalian adaptation to day-night cycles, the circadian clock is most often studied in nocturnal vertebrates such as mice. The zebrafish, in contrast, is a diurnal vertebrate. Through observation of various zebrafish larvae lacking functional eyes,2 the team of scientists has demonstrated that the latter are not needed to establish circadian rhythms that remain synchronized with light-dark ...

The who's who of bacteria: A reliable way to define species and strains

2024-03-07

What’s in a name? A lot, actually.

For the scientific community, names and labels help organize the world’s organisms so they can be identified, studied, and regulated. But for bacteria, there has never been a reliable method to cohesively organize them into species and strains. It’s a problem, because bacteria are one of the most prevalent life forms, making up roughly 75% of all living species on Earth.

An international research team sought to overcome this challenge, which has long plagued scientists who study bacteria. Kostas Konstantinidis, Richard ...

Forbes ranks the University of Colorado Denver | Anschutz Medical campus among America’s best employers

2024-03-07

The University of Colorado Denver | Anschutz Medical Campus is listed as one of Forbes America’s Best Large Employers for 2024.

The 2024 list of “America’s Best Employers” was conducted by Forbes and market research firm Statista, the world-leading statistics portal and industry ranking provider.

“This ranking is meaningful to our organization because the people who work at CU Anschutz drive our success as a leading academic medical campus by providing unparalleled patient care services, being a premier national leader in research and innovation, and fostering a supportive learning ...

NJIT professor trains college counselors to help fight antisemitism

2024-03-07

As data from the Anti-Defamation League shows antisemitism growing on college campuses in recent years and spiking after the Hamas-Israel conflict, a New Jersey Institute of Technology researcher is doing her part to combat the trend by developing a training model that will help prepare mental health professionals who work with Jewish students.

Modern students are hearing people chant slogans without understanding the intentions behind the words, or finding swastikas and other anti-Jewish graffiti on their campuses, but they are not encountering suitably trained counselors and psychologists who understand their ...

For new moms who rent, housing hardship and mental health are linked

2024-03-07

Becoming a parent comes with lots of bills. For new mothers, being able to afford the rent may help stave off postpartum depression.

“Housing unaffordability has serious implications for mental health,” said Katherine Marcal, an assistant professor at the Rutgers School of Social Work and author of a study published in the journal Psychiatry Research. “For mothers who rent their homes, the ability to make monthly payments appears to have a correlation to well-being.”

Housing hardship – missing rent or mortgage payments, moving in with others, being evicted ...

MD Anderson research highlights for March 7, 2024

2024-03-07

HOUSTON ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Research Highlights showcases the latest breakthroughs in cancer care, research and prevention. These advances are made possible through seamless collaboration between MD Anderson’s world-leading clinicians and scientists, bringing discoveries from the lab to the clinic and back.

Recent developments at MD Anderson offer clinical insights into a novel treatment strategy for patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML), molecular insights into Burkitt lymphoma development, a therapeutic target to overcome ...

Prepare workers to weather time shocks

2024-03-07

AUSTIN, Texas — Managers can do much to help their workers become more resilient to inevitable time disruptions in today’s workplace, says new research from The University of Texas at Austin.

With intricate supply chains and operations that sprawl across time zones, workplace time disturbances are only increasing. Such temporal disruptions aren’t just inconvenient, says David Harrison, Texas McCombs professor of management professor: They can carry tangible business costs, such as impaired health, increased mistakes, and reduced ...

The health impacts of migrating by sea

2024-03-07

In the four years after the border wall height was increased from 17 feet to 30 feet along the US-Mexican border, drowning deaths of migrants in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of San Diego increased by 3200%, according to a new study published in JAMA. Co-authors Anna Lussier, M.D, Ph.D. student in the University of California San Diego School of Medicine, and Peter Lindholm, M.D., Ph.D., Gurnee Endowed Chair of Hyperbaric and Diving Medicine Research and professor in residence in the Department of Emergency Medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel structural insights into Phytophthora effectors challenge long-held assumptions in plant pathology

Q&A: Researchers discuss potential solutions for the feedback loop affecting scientific publishing

A new ecological model highlights how fluctuating environments push microbes to work together

Chapman University researcher warns of structural risks at Grand Renaissance Dam putting property and lives in danger

Courtship is complicated, even in fruit flies

Columbia announces ARPA-H contract to advance science of healthy aging

New NYUAD study reveals hidden stress facing coral reef fish in the Arabian Gulf

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

Blaming beavers for flood damage is bad policy and bad science, Concordia research shows

The new ‘forever’ contaminant? SFU study raises alarm on marine fiberglass pollution

Shorter early-life telomere length as a predictor of survival

Why do female caribou have antlers?

How studying yeast in the gut could lead to new, better drugs

Chemists thought phosphorus had shown all its cards. It surprised them with a new move

A feedback loop of rising submissions and overburdened peer reviewers threatens the peer review system of the scientific literature

Rediscovered music may never sound the same twice, according to new Surrey study

Ochsner Baton Rouge expands specialty physicians and providers at area clinics and O’Neal hospital

New strategies aim at HIV’s last strongholds

Ambitious climate policy ensures reduction of CO2 emissions

Frontiers in Science Deep Dive webinar series: How bacteria can reclaim lost energy, nutrients, and clean water from wastewater

UMaine researcher develops model to protect freshwater fish worldwide from extinction

Illinois and UChicago physicists develop a new method to measure the expansion rate of the universe

Pathway to residency program helps kids and the pediatrician shortage

How the color of a theater affects sound perception

Ensuring smartphones have not been tampered with

Overdiagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer

Association of dual eligibility and medicare type with quality of postacute care after stroke

Shine a light, build a crystal

AI-powered platform accelerates discovery of new mRNA delivery materials

Quantum effect could power the next generation of battery-free devices

[Press-News.org] Shape-shifting ultrasound stickers detect post-surgical complicationsFirst-of-its-kind device ‘tags’ an organ to monitor abnormal, life-threatening fluid leaks