(Press-News.org) The fertility of both female and male tsetse flies is affected by a single burst of hot weather, researchers at the University of Bristol and Stellenbosch University in South Africa have found.

The effects of a single heatwave were even felt in the offspring of heat exposed parents, with more daughters being born than sons.

The study, published today in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, helps explain why tsetse are declining in some parts of their range in Africa and has important implications for the disease they spread, particularly sleeping sickness in humans and nagana in cattle.

Lead author Dr Hester Weaving from Bristol’s School of Biological Sciences said: “A single heatwave damaged both male and female fertility of disease-spreading tsetse flies sending populations into decline.

“Ultimately, heatwaves can drive insect biodiversity loss through both direct death and fertility losses, which is concerning given that heatwaves are increasing in frequency and intensity due to ongoing climate change.”

Scientists know that in a lot of animals, fertility is damaged at less extreme temperatures than those which kill them. In some cases, animals can become entirely sterile in response to heat, making them incapable of producing offspring. Generally, male fertility tends to be more temperature sensitive than female fertility, so the current results are surprising.

The team performed experiments in the lab using water baths at Bristol to mimic a heatwave event. To decipher if females or males were more sensitive to heatwave, they heat-exposed them separately and then paired them with unexposed members of the opposite sex. They measured how many offspring the flies produced and deaths over six weeks after the heatwave.

Dr Weaving said: “We looked at this in tsetse flies which spread the disease sleeping sickness in sub-Saharan Africa to humans, livestock and wild animals.

“They are fascinating insects as they develop a single egg at a time, feeding it as a larva in utero with a milk-like substance. The mother will then give birth to the larva which can be the same weight as themselves.”

The researchers have shown that male fertility being more heat sensitive is not common to all insects.

Senior author on the study, Dr Sinead English, said: “Our study provides important insights to how climate change will affect disease-carrying insects. We can’t assume that patterns in tsetse match those found in better-studied lab systems like seed beetles or fruit flies.”

Now further insect species should be measured to see if this result is widespread among other insect species with important implications on their global distributions in the face of climate change.

Paper:

‘Heatwaves are detrimental to fertility in the viviparous tsetse fly’ by Hester Weaving, John S Terblanche and Sinead English in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

END

Tsetse fly fertility damaged after just one heatwave, study finds

2024-03-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New UAF lidar will add to space weather research capability

2024-03-12

University of Alaska Fairbanks scientists are developing a new light detection and ranging instrument to help gain a better understanding of space weather enveloping Earth.

The new laser radar, or lidar, will be the third for the UAF Geophysical Institute. It will measure temperature and neutrally charged iron in the upper atmosphere at altitudes of 75 to 125 miles, where the mesosphere and thermosphere meet.

Understanding the processes and influences at that altitude has become increasingly important as the proliferation of low-Earth orbit satellites continues and more nations send probes through ...

A simple and robust experimental process for protein engineering

2024-03-12

Image

A protein engineering method using simple, cost-effective experiments and machine learning models can predict which proteins will be effective for a given purpose, according to a new study by University of Michigan researchers.

The method has far-reaching potential to assemble proteins and peptides for applications from industry tools to therapeutics. For instance, this technique can help speed up the development of stabilized peptides for treating diseases in ways that current medicines can't, including improving how exclusively antibodies bind to their targets in immunotherapy.

"The rules that govern how proteins work, from sequence to structure to function, are ...

UTEP researchers to design movement-based training to support local health providers

2024-03-12

EL PASO, Texas (Mar. 12, 2024) – Burnout among health care workers is a well-documented problem that can exacerbate health disparities and limit access to care. Now, researchers at The University of Texas at El Paso are taking a creative approach in their search for a solution – a training program for providers that combines elements of art and science.

The project will examine the impact of a movement-based and somatics cross-training intervention on health care providers in the Paso del ...

Alaska dinosaur tracks reveal a lush, wet environment

2024-03-12

A large find of dinosaur tracks and fossilized plants and tree stumps in far northwestern Alaska provides new information about the climate and movement of animals near the time when they began traveling between the Asian and North American continents roughly 100 million years ago.

The findings by an international team of scientists led by paleontologist Anthony Fiorillo were published Jan. 30 in the journal Geosciences. Fiorillo researched in Alaska while at Southern Methodist University. He is now executive director of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science.

University ...

Study: Best way to memorize stuff? It depends...

2024-03-12

Recent experiments by psychologists at Temple University and the University of Pittsburgh shed new light on how we learn and how we remember our real-world experiences.

The research, described in the March 12 online edition of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), suggests that varying what we study and spacing out our learning over time can both be helpful for memory — it just depends on what we’re trying to remember.

“Lots of prior research has shown that learning and ...

Exploring arctic plants and lichens: An important conservation baseline for Nunavut’s newest and largest territorial park

2024-03-12

Encompassing over 16 000 km2 of towering mountains, long fiords, lush valleys, and massive ice caps, Agguttinni Territorial Park is a protected area on northern Baffin Island, Nunavut, Canada. This park, and all of Nunavut, is Inuit Nunangat – Inuit homeland in Canada – and the park protects sites and biodiversity stewarded by Inuit since time immemorial.

Agguttinni means “where the prevailing wind occurs” in the Inuktitut local dialect. The park includes important bird areas, key habitats for polar bears and caribou, and numerous important Inuit cultural sites. It is very remote: no roads lead to it, and access ...

Multiple organ attack and immune dysregulation: Study reveals how the chikungunya virus leads to death

2024-03-12

The chikungunya virus, transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes and responsible for more than 900 deaths in Brazil since it arrived around ten years ago, is capable of spreading through the blood, reaching multiple organs and crossing the blood-brain barrier, which protects the central nervous system. The mechanisms of action observed for the first time in fatal cases by a group of Brazilian, American and British researchers were reported in an article published on March 12 in the journal Cell Host & Microbe. The findings reinforce the need ...

Setting realistic expectations for recovery after robotic lung surgery

2024-03-12

Are surgeons giving patients unrealistic expectations about recovery after robotic lung surgery? That’s what CU Department of Surgery faculty member Robert Meguid, M.D., MPH, and surgery resident Adam Dyas, M.D., set out to discover after realizing the guidance they were offering patients might be based on outdated or anecdotal information.

“Traditionally, in surgery, we're taught to tell patients that they'll be back to normal from surgery within six weeks,” says Meguid, professor of cardiothoracic ...

UCF researchers lead $1.5 million project to improve efficiency of solar cells

2024-03-12

ORLANDO – A team of researchers from the University of Central Florida and the University of Delaware’s Institute of Energy Conversion has received a $1.5 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy Solar Technologies Office to develop a novel metallization process that could improve the efficiency and lower the cost of solar cells, making solar energy more accessible to consumers.

The metallization process produces the metal contacts that are placed on the surface of silicon solar cells to ...

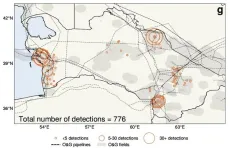

AI analysis of historical satellite images show USSR collapse in 1990s increased methane emissions, despite lower oil and gas production

2024-03-12

The collapse of the former Soviet Union in 1991 had social, political and economic effects worldwide. Among them was a suspected role in slowing human-generated methane emissions. Methane had been rising steadily in the atmosphere until about 1990. Atmospheric scientists theorized that economic collapse in the former USSR led to less oil and gas production, and thus a slowdown in the rise of global methane levels, which has since resumed.

But new University of Washington research uses early satellite records to dispute that assumption. The study, published March 12 in the ...