(Press-News.org) After birth, liver cells acquire different functions depending on their location. CNIO researchers have discovered that this specialization occurs with the onset of oral food intake, which is intermittent.

The alternation of periods with and without nutrients activates the mTOR gene and causes liver cells to specialize, which completes liver maturation.

The finding is the result of an investigation into the consequences of sedentary lifestyles and overeating in today’s society, where the body is constantly receiving nutrients.

The study is published in Nature Communications.

In mammals, the liver detects the body's energy demand at any given moment and mobilizes nutrient reserves to meet it. It is a vital function that is subdivided into multiple tasks: from releasing glucose into the blood when the hormone insulin alerts about a need for energy, to synthesizing essential fats or proteins. These tasks fall to the hepatic cells, the hepatocytes, which take care of one or the other depending on their spatial position in the liver.

Until now, it was not clear how hepatocytes were assigned tasks related to their localization. Researchers at the Spanish National Cancer Research Center (CNIO) have discovered that a gene, mTOR, is responsible for organizing the hepatocyte position map.

They also found that what triggers hepatocyte specialization is feeding after birth. The difference is marked by how nutrients reach the organism before and after birth: with no interruptions through the umbilical cord in one case, or in an intermittent fashion –when eating– in the other. The alternation of periods with and without available nutrients activates the mTOR gene and causes the hepatocytes to specialize, which completes the maturation of the liver.

The study, led by Alejo Efeyan, head of the Metabolism and Cell Signalling Group, is published in Nature Communications.

"The mTOR gene works like a GPS, telling each liver cell what to do according to the place it occupies," explains first author Ana Belén Plata Gómez. "mTOR would act like an orchestra conductor in the liver, organizing the different musical components into sections to create a coordinated (tuned) melody of metabolic functions."

A precise position in a hexagon

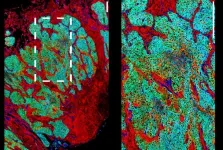

Hepatocytes are arranged in the liver forming tiny three-dimensional hexagons of about 15 concentric layers of cells. The position it occupies in the hexagon is what determines the function of each hepatocyte.

"The order of hepatocytes is already established when the liver is formed in utero, but at that time, before birth, all hepatocytes do the same thing because the supply of nutrients via the umbilical cord is constant," Efeyan explains. "Only after birth, when oral intake begins, which is intermittent, do fluctuations in that supply start to occur."

It makes then sense to coordinate the needs of the body with the resources that it receives, and also to start the spatial distribution of tasks.

This distribution is not random: "the hepatocytes that receive food, for example, perform functions that require more energy, such as producing glucose, and some fats and amino acids. But they are all highly coordinated and their functions are in many cases complementary, like in a factory production line," says Efeyan.

Looking for the consequences of a sedentary lifestyle

The finding has been a surprise that emerged in the course of another investigation. The team was studying liver maturation to observe the consequences of the sedentary lifestyle and overeating characteristic to today’s society, where the body receives nutrients all the time and produces a lot of insulin.

To reproduce this situation, they created genetically modified animal models for hepatocytes to detect constantly elevated levels of nutrients and hormones (insulin). And they observed that, after birth and with oral feeding (intermittent), the livers of these model animals never managed to diversify the tasks of the hepatocytes. They remained in a functionally immature state.

Plata Gómez, the lead author of the paper, understood then that this was because they were unable to detect the fluctuation of nutrients and insulin.

Comparison with parenteral feeding

Genetic modification in the model animals was performed in genes coordinated by the mTOR gene. It was already known that this gene intervenes in many functions related to energy expenditure and that it is activated through both food and hormones.

“By modifying mTOR, the spatial differentiation of those hepatocytes is lost” Plata Gómez explains. This gave them the clue: mTOR informs each liver cell of its function according to its location.

The team wanted to validate the extent to which this result had a real-life correlation, beyond the context of genetic manipulation. And they were able to do so thanks to the collaboration with a group of researchers from the University of Saint Louis (USA) who is researching parenteral feeding. In this kind of feeding, nutrients are supplied directly into a vein in a constant manner, without fluctuations. The USA group was studying this on newborn pigs.

The CNIO researchers who now publish their study in Nature Communications found that in the livers of these animals spatial functions are not divided either.

END

Intermittent food intake activates a 'GPS gene' in liver cells, thus completing the development of the liver after birth

2024-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists reveal chemical structural analysis in a whiff of smell

2024-03-18

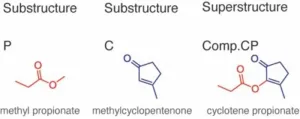

Scents, such as coffee, flowers, or freshly-baked pumpkin pie, are created by odor molecules released by various substances and detected by our noses. In essence, we are smelling molecules, the basic unit of a substance that retains its physical and chemical properties.

A research team led by Dr. ZHOU Wen from the Institute of Psychology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has discovered that this process of "smelling" involves an analysis of submolecular structural features.

The study was published online in Nature Human Behaviour on March 18.

In this study, the ...

Using light to produce medication and plastics more efficiently

2024-03-18

Anyone who wants to produce medication, plastics or fertilizer using conventional methods needs heat for chemical reactions – but not so with photochemistry, where light provides the energy. The process to achieve the desired product also often takes fewer intermediate steps. Researchers from the University of Basel are now going one step further and are demonstrating how the energy efficiency of photochemical reactions can be increased tenfold. More sustainable and cost-effective applications are now tantalizingly close.

Industrial chemical reactions ...

Mapping the evolution of urinary tract cancer cells

2024-03-18

Researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine have performed the most comprehensive analysis to date of cancer of the ureters or the urine-collection cavities in the kidney, known as upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC). The study, which compared the characteristics of primary and metastatic tumors, provides new insights into the biology of these aggressive cancers and potential ways to treat them.

In the study, which appeared March 18 in Nature Communications, the researchers examined tissue samples from 44 primary and metastatic UTUC tumors. They compared gene mutations ...

Implantable sensor could lead to timelier Crohn’s treatment

2024-03-18

· Temperature sensor warns of disease flareups, tracks disease progression in real time

· Currently no way to quickly detect inflammation, leading to invasive surgeries

· Strategy could be useful in ulcerative colitis, another inflammatory bowel disease

CHICAGO --- A team of Northwestern University scientists has developed the first wireless, implantable temperature sensor to detect inflammatory flareups in patients with Crohn’s disease. The approach offers long-term, real-time monitoring and ...

Glucose levels affect cognitive performance in people with type 1 diabetes differently

2024-03-18

A new study led by researchers at McLean Hospital (a member of Mass General Brigham) and Washington State University used advances in digital testing to demonstrate that naturally occurring glucose fluctuations impact cognitive function in people with Type 1 Diabetes (T1D). Results showed that cognition was slower in moments when glucose was atypical – that is, considerably higher or lower than someone’s usual glucose level. However, some people were more susceptible to the cognitive effects of large glucose fluctuations than others.

“In trying to understand how diabetes impacts the brain, our research shows that it is important to consider not only how people ...

Mimicking exercise with a pill

2024-03-18

NEW ORLEANS, March 18, 2024 — Doctors have long prescribed exercise to improve and protect health. In the future, a pill may offer some of the same benefits as exercise. Now, researchers report on new compounds that appear capable of mimicking the physical boost of working out — at least within rodent cells. This discovery could lead to a new way to treat muscle atrophy and other medical conditions in people, including heart failure and neurodegenerative disease.

The researchers will present their ...

New composite decking could reduce global warming effects of building materials

2024-03-18

NEW ORLEANS, March 18, 2024 — Buildings and production of the materials used in their construction emit a lot of carbon dioxide (CO2), a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming and climate change. But storing CO2 in building materials could help make them more environmentally friendly. Scientists report that they have designed a composite decking material that stores more CO2 than is required to manufacture it, providing a “carbon-negative” option that meets building codes and is less expensive than standard composite decking.

The researchers will present their results today at the spring meeting of the American Chemical Society ...

Artificial mucus identifies link to tumor formation

2024-03-18

NEW ORLEANS, March 18, 2024 – During cold and flu season, excess mucus is a common, unpleasant symptom of illness, but the slippery substance is essential to human health. To better understand its many roles, researchers synthesized the major component of mucus, the sugar-coated proteins called mucins, and discovered that changing the mucins of healthy cells to resemble those of cancer cells made healthy cells act more cancer-like.

The researcher will present her results today at the spring meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS). ACS Spring 2024 is a hybrid meeting being held virtually and in person March 17-21; it features nearly 12,000 ...

Study explores homeless women’s experiences of ‘period poverty’

2024-03-18

Research from the University of Southampton has identified common issues women face when experiencing periods while homeless.

A review of research published in Women and Health has found homeless women experienced practical challenges in managing menstruation alongside feelings of embarrassment and shame, with many ‘making do’ due to inadequate provision.

The researchers say it’s high time to address the provision of menstrual health resources as a basic human right.

Dr Stephanie Barker, a teaching fellow at the University of ...

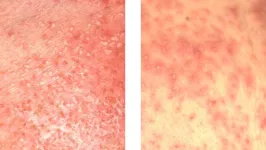

Keeping score: novel method might help differentiate 2 serious skin diseases

2024-03-18

Your skin becomes red and spots filled with pus appear, so you visit a dermatologist. When these symptoms spread to the skin throughout the body, it is difficult for the physician to distinguish whether it is generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) or acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), as both have similar symptoms. The two diseases run different courses and require different treatments. Without proper treatment, the symptoms can worsen severely and cause complications, so it is essential to distinguish between them.

Researchers ...