(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- The humble peat bog conjures images of a brown, soggy expanse. But it turns out to have a superpower in the fight against climate change.

For thousands of years, the world’s peatlands have absorbed and stored vast amounts of carbon dioxide, keeping this greenhouse gas in the ground and not in the air. Although peatlands occupy just 3% of the land on the planet, they play an outsized role in carbon storage -- holding twice as much as all the world’s forests do.

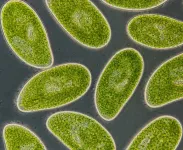

The fate of all that carbon is uncertain in the face of climate change. And now, a new study suggests that the future of this vital carbon sink may be affected, at least in part, by tiny organisms that are often overlooked.

Most of the carbon in peatlands is locked up in the spongy layers of mosses, dead and alive, that carpet the ground. There, the cold, waterlogged, oxygen-starved conditions make it hard for plants to decompose. This keeps the carbon they absorbed during photosynthesis locked up in the soil instead of leaking into the atmosphere.

But rising global temperatures are drying peatlands out, turning them from carbon sinks to potential carbon sources.

In a study published March 3 in the journal Global Change Biology, a team led by Duke biology professor Jean Philippe Gibert and doctoral student Christopher Kilner tested the effects of climate change on little creatures called protists that live among the peatland mosses.

Not only are protists abundant -- collectively, they weigh twice as much as all the animals on the planet -- they also play a role in the overall movement of carbon between peatlands and the atmosphere.

That’s because as protists go about the business of life -- eating, reproducing -- they suck in and churn out carbon too.

Some protists draw in CO2 from the air to fuel their growth. Other protists are predators, gobbling up nitrogen-fixing bacteria the peatland mosses rely on to stay healthy.

In a bog in northern Minnesota, researchers led by Oak Ridge National Laboratory have built 10 open-topped enclosures, each 40 feet across, designed to mimic various global warming scenarios.

The enclosures are controlled at different temperatures, ranging from no warming all the way up to 9 degrees Celsius warmer than the surrounding peatland.

Half of the enclosures were grown in normal air. The other half were exposed to carbon dioxide levels more than two times higher than today’s, which we could reach by the end of the century if the burning of fossil fuels is left unchecked.

Five years after the simulation experiment began, the Duke team was already seeing some surprising changes.

“The protists started behaving in ways that we didn't expect,” Kilner said.

At current CO2 levels, most of the more than 200,000 protists they measured became more abundant with warming. But under elevated CO2 that trend reversed.

What’s more, the combined effects of warming and elevated CO2 led to a reshuffling in the protists’ feeding habits and other traits known to influence how much CO2 they give off during respiration -- in other words, how much they contribute to climate change themselves.

Exactly what such changes could mean for peatlands’ future ability to mitigate climate change is unclear, but they’re likely to be important.

Overall, the results show that a neglected part of the peatlands’ microbial food web is sensitive to climate change too, and in ways that “are currently not accounted for in models that predict future warming,” Gibert said.

This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DE-SC0020362). Other authors include Alyssa Carrell, Dale Pelletier and David Weston of Oak Ridge National Laboratory; and Daniel Wieczynski, Samantha Votzke, Katrina DeWitt, Andrea Yammine, and Jonathan Shaw of Duke.

CITATION: "Temperature and CO2 Interactively Drive Shifts in the Compositional and Functional Structure of Peatland Protist Communities," Christopher L. Kilner, Alyssa A. Carrell, Daniel J. Wieczynski, Samantha Votzke, Katrina DeWitt, Andrea Yammine, Jonathan Shaw, Dale A. Pelletier, David J. Weston, and Jean P. Gibert. Global Change Biology, March 3, 2024. DOI: https://doi-org.proxy.lib.duke.edu/10.1111/gcb.17203

END

Climate change alters the hidden microbial food web in peatlands

Here's why that matters

2024-03-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Text nudges can increase uptake of COVID-19 boosters– if they play up a sense of ownership of the vaccine

2024-03-18

New research published in Nature Human Behavior suggests that text nudges encouraging people to get the COVID-19 vaccine, which had proven effective in prior real-world field tests, are also effective at prompting people to get a booster.

The key in both cases is to include in the text a sense of ownership in the dose awaiting them.

The paper, led by Hengchen Dai, an associate professor of management and organizations and behavioral decision making at the UCLA Anderson School of Management, and Silvia Saccardo, an associate professor of social and decision sciences at Carnegie Mellon University, draws on previous research published in Nature that examined the effectiveness ...

A new study shows how neurochemicals affect fMRI readings

2024-03-18

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – The brain is an incredibly complex and active organ that uses electricity and chemicals to transmit and receive signals between its sub-regions.

Researchers have explored various technologies to directly or indirectly measure these signals to learn more about the brain. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), for example, allows them to detect brain activity via changes related to blood flow.

Yen-Yu Ian Shih, PhD, professor of neurology and associate director of UNC’s Biomedical Research Imaging Center, and his fellow lab members have long been curious about how neurochemicals in the brain regulate and influence neural activity, ...

Digital reminders for flu vaccination improves turnout, but not clinical outcomes in older adults

2024-03-18

Embargoed for release until 5:00 p.m. ET on Monday 18 March 2024

Annals of Internal Medicine Tip Sheet

@Annalsofim

Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf of the organization they represent.

----------------------------

1. Digital reminders for flu vaccination improves ...

Avatar will not lie... or will it? Scientists investigate how often we change our minds in virtual environments

2024-03-18

How confident are you in your judgments and how well can you defend your opinions? Chances are that they will change under the influence of a group of avatars in a virtual environment. Scientists from SWPS University investigated the human tendency to be influenced by the opinions of others, including virtual characters.

We usually conform to the views of others for two reasons. First, we succumb to group pressure and want to gain social acceptance. Second, we lack sufficient knowledge and perceive the group as a source of a better interpretation of the current situation, describes Dr. Konrad Bocian from the Institute of Psychology at SWPS University.

So far, only a few studies ...

8-hour time-restricted eating linked to a 91% higher risk of cardiovascular death

2024-03-18

Research Highlights:

A study of over 20,000 adults found that those who followed an 8-hour time-restricted eating schedule, a type of intermittent fasting, had a 91% higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease.

People with heart disease or cancer also had an increased risk of cardiovascular death.

Compared with a standard schedule of eating across 12-16 hours per day, limiting food intake to less than 8 hours per day was not associated with living longer.

Embargoed until 3 p.m. CT/4 p.m. ET, Monday, March 18, 2024

CHICAGO, March 18, 2024 — An analysis ...

Alternative tidal wetlands in plain sight overlooked Blue Carbon superstars

2024-03-18

Blue Carbon projects are expanding globally; however, demand for credits outweighs the available credits for purchase.

Currently, only three types of wetlands are considered Blue Carbon ecosystems: mangroves, saltmarsh and seagrass.

However, other tidal wetlands also comply with the characteristics of what is considered Blue Carbon, such as tidal freshwater wetlands, transitional forests and brackish marshes.

In a new study, scientists from Australia, Indonesia, Singapore, South Africa, Vietnam, the US and Mexico have highlighted the increasing opportunities for Blue Carbon projects for the conservation, restoration and improved management of highly threatened ...

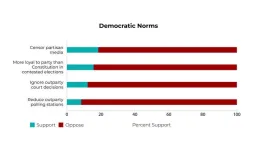

The majority of Americans do not support anti-democratic behavior, even when elected officials do

2024-03-18

EMBARGOED UNTIL MARCH 18 AT 3 P.M. EST

Recently, fundamental tenets of democracy have come under threat, from attempts to overturn the 2020 election to mass closures of polling places.

A new study from the Polarization Research Lab, a collaboration among researchers at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania, Dartmouth College, and Stanford University, has found that despite this surge in anti-democratic behavior by U.S. politicians, the majority of Americans oppose anti-democratic attitudes and reject partisan violence.

From September 2022 to October 2023, a period which included the 2022 midterm ...

Genes identified that allow bacteria to thrive despite toxic heavy metal in soil

2024-03-18

VANCOUVER, Wash. -- Some soil bacteria can acquire sets of genes that enable them to pump the heavy metal nickel out of their systems, a study has found. This enables the bacteria to not only thrive in otherwise toxic soils but help plants grow there as well.

A Washington State University-led research team pinpointed a set of genes in wild soil bacteria that allows them to do this in serpentine soils which have naturally high concentrations of toxic nickel. The genetic discovery, detailed in the journal Proceedings of the National Academies ...

Scientists’ discovery could reduce dependence on animals for vital anti-blood clot drug

2024-03-18

Heparin, the world’s most widely used blood thinner, is used during procedures ranging from kidney dialysis to open heart surgery. Currently, heparin is derived from pig intestines, but scientists at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have discovered how to make it in the lab. They have also developed a path to a biomanufacturing process that could potentially revolutionize how the world gets its supply of this crucial medicine.

“In recent years, with disease and contamination issues disrupting the global supply chain of pig heparin and potentially putting millions of patients at risk, it’s clear we need to diversify ...

Artificial streams reveal how drought shapes California’s alpine ecosystems

2024-03-18

Berkeley — A network of artificial streams is teaching scientists how California’s mountain waterways — and the ecosystems that depend on them — may be impacted by a warmer, drier climate.

Over the next century, climate change is projected to bring less snowfall to the Sierra Nevada. Smaller snowpacks, paired with warmer conditions, will shift the annual snowmelt earlier into the year, leaving less water to feed streams and rivers during the hot summer months. By 2100, mountain streams are predicted to reach their annual base, or “low-flow,” conditions an average of six ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Wildfire smoke linked to rise in violent assaults, new 11-year study finds

New technology could use sunlight to break down ‘forever chemicals’

Green hydrogen without forever chemicals and iridium

Billion-DKK grant for research in green transformation of the built environment

For solar power to truly provide affordable energy access, we need to deploy it better

Middle-aged men are most vulnerable to faster aging due to ‘forever chemicals’

Starving cancer: Nutrient deprivation effects on synovial sarcoma

Speaking from the heart: Study identifies key concerns of parenting with an early-onset cardiovascular condition

From the Late Bronze Age to today - Old Irish Goat carries 3,000 years of Irish history

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

[Press-News.org] Climate change alters the hidden microbial food web in peatlandsHere's why that matters