(Press-News.org) Using data from both mice and humans, a Johns Hopkins Medicine research team has found that a cell surface protein that senses odors and chemicals may be responsible for — and help explain — sex differences in mammalian blood pressure. The unusual connection between such protein receptors and sex differences in blood pressure, reported in the March 20 issue of Science Advances, may lead to a better understanding of long known differences in blood pressure between females and males.

Blood pressure in premenopausal human and mouse females is typically 10 points lower in both diastolic and systolic pressure than in males. Some studies suggest the difference may be caused by sex hormones, but the biological basis for the variation is not entirely clear.

“Despite the well-known differences in blood pressure between females and males, most clinical guidelines have the same thresholds for treatment,” says Jennifer Pluznick, Ph.D., associate professor of physiology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “Taking a closer look at the fundamental, scientific basis for sex differences in blood pressure may eventually help clinicians think about blood pressure treatment in new ways.”

Pluznick is a basic scientist who has found unique roles for so-called olfactory receptors in various organs of the body. The tiny proteins on the surface of cells essentially sniff out nearby odors or other chemicals.

The Johns Hopkins team began their studies looking for the locations in the body where a specific olfactory receptor — Olfr558 — is found. Olfr558 is one of three olfactory receptors (out of about 350 total) that are well-conserved by evolution in many mammals, including humans and mice. The human version of the receptor is called OR51E1.

Previously, the Johns Hopkins team found Olfr558 in the kidney, and other studies have located the receptor in other organs, aside from the cells responsible for scent detection in the nose.

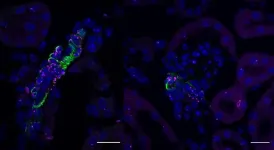

For this study, the researchers found the receptor in blood vessel cells in the kidney and in juxtaglomerular granular cells, a type of kidney cell that secretes the hormone renin, which plays a key role in regulating blood pressure.

“This was our first indication that we should take a closer look at the impact of Olfr558 on blood pressure,” says Pluznick.

Next, the team, led by Pluznick and research associate Jiaojiao Xu, Ph.D., measured blood pressure in young female and male mice during active and resting timeframes. Male mice with normal levels of the Olfr558 receptor typically had diastolic and systolic blood pressure 10 points higher than female mice.

However, when the researchers looked at young female and male mice genetically engineered to lack the gene for the Olfr558 receptor, they found that blood pressure increased in female mice but decreased in male mice, such that the sex difference in blood pressure disappeared.

Preliminary data from the Johns Hopkins team point to blood vessel stiffness and renin hormone levels in the blood as potential reasons for the lack of blood pressure variation in mice without the receptor.

The research team also analyzed genomic information on human tissue data stored in the U.K. Biobank, focusing on people with a rare variation in the human version of the olfactory receptor OR51E1. Their analysis showed that females and males younger than 50 with the variant do not show the typical sex-linked differences in blood pressure.

The research team cautioned that their work has not identified a direct molecular signaling pathway that would pin down the link between the olfactory receptor and blood pressure variation. Those studies have yet to be done.

Pluznick’s team will try, in future experiments, to pinpoint the precise cell types that govern the receptor-blood pressure link.

“We hope that improving our understanding of the basic biology of this new link will provide insights on blood pressure regulation for both sexes,” says Pluznick.

Support for this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [R56DK107726], the National Institute on Aging [R21AG081683], the American Heart Association Established Investigator Award, the NIHR Cardiovascular Biomedical Centre at Barts and the Queen Mary University of London.

In addition to Pluznick and Xu, researchers who contributed to this study are Rira Choi, Kunal Gupta and Lakshmi Santhanam from Johns Hopkins and Helen Warren from the Queen Mary University of London.

END

Study suggests an ‘odor sensor’ may explain male and female differences in blood pressure

2024-03-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Repairing patients’ dura more durably

2024-03-20

Repairing patients’ dura more durably

Highly adhesive and mechanically strong Dural Tough Adhesive addresses multiple limitations in the repair of the dural membrane lining the brain and spinal cord after trauma and surgeries.

By Benjamin Boettner

(BOSTON) — The dural membrane (dura) is the outermost of three meningeal layers that line the central nervous system (CNS), which includes the brain and spinal cord. Together, the meninges function as a shock-absorber to protect the CNS against trauma, circulate nutrients throughout the CNS, as well as remove waste. The dura also is a critical biological barrier that contains cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) surrounding ...

Quantum talk with magnetic disks

2024-03-20

Quantum computers promise to tackle some of the most challenging problems facing humanity today. While much attention has been directed towards the computation of quantum information, the transduction of information within quantum networks is equally crucial in materializing the potential of this new technology. Addressing this need, a research team at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR) is now introducing a new approach for transducing quantum information: the team has manipulated quantum bits, so called qubits, by harnessing the magnetic field ...

Earlier retirement for people with chronic musculoskeletal pain

2024-03-20

Frequent musculoskeletal pain is linked with an increased risk of exiting work and retiring earlier, according to a new study from the University of Portsmouth.

The paper published this week in open-access journal PLOS ONE found the association between musculoskeletal pain and retiring earlier persisted even after accounting for working conditions, job satisfaction and sex.

Dr Nils Niederstrasser and colleagues used data on 1,156 individuals aged 50+ living in England who took part in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Over the course of the 14-year data collection period, 1,073 of the individuals retired.

The researchers found that people with musculoskeletal ...

Tiny magnetic implants enable wireless healthcare monitoring

2024-03-20

A millimeter-scale, chip-less and battery-less implant can wirelessly monitor a series of parameters within your body and communicate with a wearable device attached on the skin. In a recent study published in the journal Science Advances, researchers from Peking University have unveiled a miniaturized implantable sensor capable of health monitoring without the need of transcutaneous wires, integrated circuit chips, or bulky readout equipment, thereby reducing infection risks, improving biocompatibility, and enhancing portability.

Han Mengdi from Peking University, the lead researcher of ...

New study suggests that while social media changes over decades, conversation dynamics stay the same

2024-03-20

Published in Nature, a new study has identified recurring, ‘toxic’ human conversation patterns on social media, which are common to users irrespective of the platform used, the topic of discussion, and the decade in which the conversation took place.

In particular, the study suggests that prolonged conversations on social media are more prone to toxicity, and polarisation, when divergent viewpoints from debate lead to an escalation of online disagreement.

Contrary to the prevailing assumption, the study suggests that toxic interactions do not deter users from engagement, they actively participate in conversations. It also suggests that toxicity ...

Study finds non-immune brain cells can acquire immune memory, may drive CNS pathologies like multiple sclerosis

2024-03-20

Immunological memory — the ability to respond to a previously encountered antigen, or foreign substance, with greater speed and intensity on re-exposure is a hallmark of adaptive immunity. Innate immune cells also develop metabolic and epigenetic memories that boost their responses, but it was previously unknown if non-immune cells like astrocytes, which interact with immune cells and contribute to inflammation in the central nervous system (CNS), acquire aspects of immune memory of encountering ...

Canada should ban all unhealthy food marketing children may be exposed to

2024-03-20

Quebec City, March 20, 2024–Canada should ban marketing of unhealthy foods wherever children may be exposed, whether on TV, social media or billboards. This is one of the main conclusions of a Canada-wide study involving more than fifty food and nutrition experts made public today by a team from Université Laval's Faculty of Agriculture and Food Sciences.

The study, conducted as part of a research program funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, also recommends better funding ...

The 7th World Conference on Targeting Phage Therapy, taking place in Malta in 2024, will showcase current developments in phage therapy and offer strategic insights into its future directions

2024-03-20

The 7th World Conference on Targeting Phage Therapy 2024 is set to take place on June 20-21 at the Corinthia Palace Malta, introducing the latest advancements within the field of phage research and therapy.

Robert T. Schooley, M.D., Professor of Medicine at the University of California, San Diego, and Co-Director of the Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics, will lead the discourse, presenting insights and strategies essential to Phage Therapy in his talk titled "Phage Therapeutics 2024: Essential Translational Research Components for Clinical Trials."

Agenda at a Glance

Day One: will focus on Phages, Hosts & Microbiome, exploring ...

Companies reluctant to pay extra to confirm suppliers’ sustainability claims

2024-03-20

Many companies proclaiming ethical credentials resist paying a premium to test their suppliers’ sustainability claims, new research suggests.

A team from Bayes Business School (formerly Cass), City, University of London, studied responses from 234 managers with procurement decision-making powers.

While buyers’ purchasing decisions are not solely price-driven, the team found, they are often happy to accept suppliers’ reassurances about sustainability rather than pay a premium for third party verification. Despite accepting ...

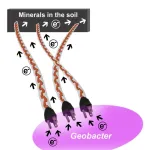

Deep Earth electrical grid mystery solved

2024-03-20

To “breathe” in an environment without oxygen, bacteria in the ground beneath our feet depend upon a single family of proteins to transfer excess electrons, produced during the “burning” of nutrients, to electric hairs called nanowires projecting from their surface, found by researchers at Yale University and NOVA School of Science and Technology, NOVA University Lisbon (NOVA-FCT).

This family of proteins in essence acts as plugs that power these nanowires to create a natural electrical ...