(Press-News.org) EMBARGOED UNTIL MARCH 25, 2024 AT 3:00 PM US EST

What could cancer teach us about tuberculosis? That’s a question Meenal Datta has been chasing since she was a graduate student.

Once the body’s immune system is infected with tuberculosis, it forms granulomas — tight clusters of white blood cells — in an attempt to wall off the infection-causing bacteria in the lungs. But more often than not, granulomas do more harm than good.

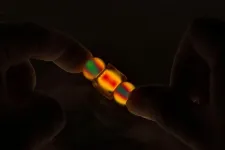

Charged with analyzing the similarities between granulomas and tumors, Datta discovered that both are structurally and functionally abnormal. In 2015, she and other researchers looked at the vascular structures of granulomas and showed that they are compromised and leaky just like tumor blood vessels, which limits drug delivery and successful treatment in both diseases.

“It was the first time we showed definitively that there was this pathophysiological similarity between these two diseases that present with different causes and symptoms,” said Datta, assistant professor of aerospace and mechanical engineering at the University of Notre Dame. “Cancer doesn’t sound anything like an infectious disease. And yet, here are two different diseases with the same problem of dysfunctional blood vessels.”

Now a study from the same team at the University of Notre Dame, Massachusetts General Hospital and the National Institutes of Health has identified a combination of medications that may improve blood flow within granulomas, benefiting drug delivery. Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study leverages decades of cancer research to study tuberculosis-affected lung tissue and improve treatment.

“Much like in tumors, many of the blood vessels in granulomas are compressed or squeezed shut — just like if you stepped on your garden hose,” said Datta, the first author on the study. “In cancer, we know that happens because of the growing tumor mass and the supportive protein scaffolding it puts down, called matrix. We thought maybe the same thing was happening in tuberculosis.”

The study confirmed that a similar phenomenon is occurring in granulomas — too much cell mass and protein scaffolding. This impaired function makes blood flow through blood vessels nearly impossible, crippling the ability to get a medication to the tuberculosis disease site.

Datta and her collaborators used losartan, an affordable drug used to treat high blood pressure. However, it also has the beneficial side effect of reducing the amount of matrix being created inside a granuloma, thus opening the compressed blood vessels and restoring blood flow.

Researchers then combined losartan with bevacizumab, a drug used by cancer patients to stop the overproduction of poorly formed blood vessels. With this two-pronged medicinal approach, Datta and the team were able to make the granuloma blood vessels function and behave more normally.

When the researchers applied the host-directed therapies losartan and bevacizumab along with antibiotics, they showed improved drug delivery and antibiotic concentration within granulomas.

Additionally, Datta’s graduate student Maksym Zarodniuk analyzed genome sequencing data produced by the team, and found that even without antibiotics, there was a reduction in tuberculosis bacteria within the granulomas.

“When we gave just those host-directed therapies, we were getting good treatment benefit even without adding the antibiotics. Those therapies were promoting the body’s inflammatory response to fight against the bacteria, which we did not expect,” Datta said.

For Datta, this study caps off a stretch of tuberculosis research that started when she began her doctoral research at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in 2011, and has spanned multiple phases of her career. Tuberculosis, although largely controlled in the U.S., is still considered one of the deadliest infectious diseases worldwide.

“The advantage of the host-directed therapies we selected is that these agents or very similar drugs of the same class are already approved by regulatory agencies around the globe, and they are affordable,” Datta said. “We hope that our preclinical results will be found compelling enough to start a clinical trial to benefit tuberculosis patients.”

Today, Datta’s lab at the University of Notre Dame primarily focuses its research on understanding glioblastoma, a rare treatment-resistant brain cancer. Datta said that being an engineer allows her to cross into other areas of research and with a different perspective, making an excellent case for the importance of multidisciplinary research.

“I do believe that really is an advantage of being an engineer. It’s easier for me to sometimes make connections between contexts that seem disparate,” Datta said. “We depend on our life science and clinical colleagues to walk through those details, but engineers are very good at approaching complex problems from a simplified systems approach.”

The study, “Normalizing granuloma vasculature and matrix improves drug delivery and reduces bacterial burden in tuberculosis-infected rabbits,” was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. Datta is an affiliated member of Notre Dame’s Berthiaume Institute for Precision Health, Eck Institute for Global Health, Harper Cancer Research Institute, Lucy Family Institute for Data and Society, NDnano and Warren Center for Drug Discovery. Datta is an assistant professor in the following doctorate programs: aerospace and mechanical engineering, bioengineering, and materials science and engineering.

Contact: Brandi Wampler, associate director of media relations, 574-631-2632, brandiwampler@nd.edu

END

Cancer therapies show promise in combating tuberculosis

2024-03-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Gotta go? New bladder device lets you know

2024-03-25

Should you run to the bathroom now? Or can you hold it until you get home? A new implant and associated smartphone app may someday remove the guess work from the equation.

Northwestern University researchers have developed a new soft, flexible, battery-free implant that attaches to the bladder wall to sense filling. Then, it wirelessly — and simultaneously — transmits data to a smartphone app, so users can monitor their bladder fullness in real time.

The study will be published next week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). It ...

Seeing the forest for the trees: Species diversity is directly correlated with productivity in eastern U.S. forests

2024-03-25

When scientists and policymakers make tough calls on which areas to prioritize for conservation, biodiversity is often their top consideration. Environments with more diversity support a greater number of species and provide more ecosystem services, making them the obvious choice.

There’s just one problem. There are several ways to measure diversity, and each reveals a slightly different, and sometimes conflicting, view of how life interacts in a forest or other ecosystem.

In a new study published ...

Pairing crypto mining with green hydrogen offers clean energy boost

2024-03-25

ITHACA, N.Y. – Pairing cryptocurrency mining – notable for its outsize consumption of carbon-based fuel – with green hydrogen could provide the foundation for wider deployment of renewable energy, such as solar and wind power, according to a new Cornell University study.

“Since current cryptocurrency operations now contribute heavily to worldwide carbon emissions, it becomes vital to explore opportunities for harnessing the widespread enthusiasm for cryptocurrency as we move toward a sustainable and a climate-friendly future,” said Fengqi You, professor of energy systems engineering at Cornell.

You and doctoral ...

With a new experimental technique, MIT engineers probe the mechanisms of landslides and earthquakes

2024-03-25

Granular materials, those made up of individual pieces, whether grains of sand or coffee beans or pebbles, are the most abundant form of solid matter on Earth. The way these materials move and react to external forces can determine when landslides or earthquakes happen, as well as more mundane events such as how cereal gets clogged coming out of the box. Yet, analyzing the way these flow events take place and what determines their outcomes has been a real challenge, and most research has been confined to two-dimensional experiments that don’t ...

MinJun Kim inducted into the 2024 Class of the AIMBE College of Fellows

2024-03-25

The American Institute for Medical and Biological Engineering (AIMBE) has announced the induction of MinJun Kim, Robert C. Womack Endowed Chair Professor in Engineering at Southern Methodist University to its College of Fellows.

Election to the AIMBE College of Fellows is among the highest professional distinctions accorded to medical and biological engineers, comprised of the top two percent of engineers in these fields. College membership honors those who have made outstanding contributions to "engineering and medicine research, practice, or education” and to “the pioneering of new and developing fields of technology, making major advancements in traditional ...

Global study could change how children with multiple sclerosis are treated

2024-03-25

A ground-breaking study – the largest of its kind globally – has found children with multiple sclerosis (MS) have better outcomes if treated early and with the same high-efficacy therapies as adults.

There are a limited number of therapies approved for children with MS, with only one considered to be of high-efficacy – meaning highly effective.

However, a Royal Melbourne Hospital (RMH) observational study has determined that paediatric patients should be treated with the same high-efficacy ...

NRL scientists deliver quantum algorithm to develop new materials and chemistry

2024-03-25

WASHINGTON – U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) scientists published the Cascaded Variational Quantum Eigensolver (CVQE) algorithm in a recent Physical Review Research article, expected to become a powerful tool to investigate the physical properties in electronic systems.

The CVQE algorithm is a variant of the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm that only requires the execution of a set of quantum circuits once rather than at every iteration during the parameter optimization process, thereby increasing the computational throughput.

“Both algorithms ...

Bengal cat coats are less wild than they look, genetic study finds

2024-03-25

Bengal cats are prized for their appearance; the exotically marbled and spotted coats of these domestic pets make them look like small, sleek jungle cats. But the origin of those coats — assumed to come from the genes of Asian leopard cats that were bred with house cats — turns out to be less exotic.

Stanford Medicine researchers, in collaboration with Bengal cat breeders, have discovered that the Bengal cats’ iridescent sheen and leopard-like patterns can be traced to domestic cat genes that were aggressively selected for after the cats were bred with wild cats.

“Most ...

Transmasculine people report higher dietary supplement use than general population

2024-03-25

More than 1 million people in the United States identify as transgender; however, there is limited research on nutrition-related health outcomes for transgender people. To narrow the research gap, Mason MS, Nutrition student Eli Kalman-Rome investigated common motivations of dietary supplement use in transmasculine people. The study defined transmasculine as people on the transgender and gender-nonbinary spectrum who were assigned female at birth.

Transmasculine people reported a higher use of dietary supplements (65%) compared to the total U.S. population (22.5%), according to the study. 90% of transmasculine participants reported using supplements ...

Neuroscience and Society Series: aligning science with the public’s values

2024-03-25

Research that involves implanting devices into the brains of human volunteers creates a special moral obligation that extends beyond the trial period—an obligation that researchers, device manufacturers, and funders owe to the volunteers. This is the conclusion of two new essays in the Hastings Center Report that launch a series on the ethical and social issues raised by brain research.

The “Neuroscience and Society” series is supported by the Dana Foundation and will be published in open-access format online over the next three years.

The series seeks to promote deliberative public engagement about neuroscience, writes Hastings Center senior ...