(Press-News.org) Blood is a remarkable material: it must remain fluid inside blood vessels, yet clot as quickly as possible outside them, to stop bleeding. The chemical cascade that makes this possible is well understood for vertebrate blood. But hemolymph, the equivalent of blood in insects, has a very different composition, being notably lacking in red blood cells, hemoglobin, and platelets, and having amoeba-like cells called hemocytes instead of white blood cells for immune defense.

Just like blood, hemolymph clots quickly outside the body. How it does so has long remained an enigma. Now, materials scientists have shown in Frontiers in Soft Matter how this feat is managed by caterpillars of the Carolina sphinx moth. This discovery has potential applications for human medicine, the authors said.

“Here we show that these caterpillars, called tobacco hornworms, can seal the wounds in a minute. They do that in two steps: first, in a few seconds, their thin, water-like hemolymph becomes ‘viscoelastic’ or slimy, and the dripping hemolymph retracts back to the wound,” said senior author Dr Konstantin Kornev, a professor at the Department of Materials Science and Engineering of Clemson University.

“Next, hemocytes aggregate, starting from the wound surface and moving up to embrace the coating hemolymph film that eventually becomes a crust sealing the wound.”

Challenging to study

Fully grown tobacco hornworms, ready to pupate, are between 7.5cm and 10cm long. They only contain a minute amount of hemolymph, which typically clots within seconds, which makes it hard to study with conventional methods.

For these reasons, Kornev and colleagues had to develop new techniques for the present study, and work fast. Even so, the failure rate for the trickiest manipulations was enormous (up to 95%), requiring many attempts.

They restrained individual hornworms in a plastic sleeve, and made a slight wound in one of each caterpillar’s pseudolegs through a window in the sleeve. They then touched the dripping hemolymph with a metal ball, which was pulled away, creating a hemolymph ‘bridge’ (about two millimeters long and hundreds micrometers wide) that subsequently narrowed and broke, producing satellite droplets. Kornev et al. filmed these events with a high frame rate camera and macro lens, to study them in detail.

Instantaneous change in properties

These observations suggested that during the first approximately five seconds after starting to flow, hemolymph behaved similarly to water: in technical terms, like a Newtonian, low viscosity liquid. But within the next 10 seconds, the hemolymph underwent a marked change: it now did not break instantaneously but formed a long bridge behind the falling drop. Typically, bleeding stopped completely after 60 to 90 seconds, after a crust formed over the wound.

Kornev et al. studied the hemolymph’s flow properties further by placing a 10-micrometer-long nickel nanorod in a droplet of fresh hemolymph. When a rotating magnetic field caused the nanorod to spin, its lag relative to the magnetism gave an estimate of the hemolymph’s ability to hold the rod back through viscosity.

They concluded that within seconds after leaving the body, caterpillar hemolymph changes from a low-viscous into a viscoelastic fluid.

“A good example of a viscoelastic fluid is saliva,” said Kornev. “When you smear a drop between your fingers, it behaves like water: materials scientists will say it is purely viscous. But thanks to very large molecules called mucins in it, saliva forms a bridge when you move your fingers apart. Therefore, it’s properly called viscoelastic: viscous when you shear it and elastic when you stretch it.”

The scientists further used optical phase-contrast and polarized microscopy, X-ray imaging, and materials science modeling to study the cellular processes by which hemocytes aggregate to form a crust over a wound. They did this not only in Carolina sphinx moths and their caterpillars, but also in 18 other insect species.

Hemocytes are key

The results showed that hemolymph of all species studied reacted similarly to shear. But its reaction to stretching differed drastically between the hemocyte-rich hemolymph of caterpillars and cockroaches on the one hand, and the hemocyte-poor hemolymph of adult butterflies and moths on the other: droplets stretched out to form bridges for the first two, but immediately broke for the latter.

“Turning hemolymph into a viscoelastic fluid appears to help caterpillars and cockroaches to stop any bleeding, by retracting dripping droplets back to the wound in a few seconds,” said Kornev. “We conclude that their hemolymph has an extraordinary ability to instantaneously change its material properties. Unlike silk-producing insects and spiders, which have a special organ for making fibers, these insects can make hemolymph filaments at any location upon wounding.”

The scientists concluded that hemocytes play a key role in all these processes. But why caterpillars and cockroaches need more hemocytes than adult butterflies and moths is still unknown.

“Our discoveries open the door for designing fast-working thickeners of human blood. We needn’t necessarily copy the exact biochemistry, but should focus on designing drugs that could turn blood into a viscoelastic material that stops bleeding. We hope that our findings will help to accomplish this task in the near future,” said Kornev.

END

Scientists discover how caterpillars can stop their bleeding in seconds

Insect blood has ‘extraordinary ability’ to change its material properties, and may help develop new drugs for humans

2024-03-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Spot-on laser treatment for skin blemishes becoming clearer with new index

2024-03-27

Many people bothered by skin blemishes might turn to laser treatment. To improve efficacy and reduce complications from such laser treatment, an Osaka Metropolitan University-led research group has developed an index of the threshold energy density, known as fluence, and the dependent wavelength for picosecond lasers.

Picosecond lasers have in recent years been used to remove pigmented lesions. These lasers deliver energy beams in pulses that last for about a trillionth of a second. The lasers target melanosomes, which produce, store, ...

Scientists warn: The grey seal hunt is too large

2024-03-27

Researchers at the University of Gothenburg warn that today's hunting quotas of about 3,000 animals pose a risk to the long-term survival of the grey seal in the Baltic Sea. The conclusions of this new study are based on statistics from 20th century seal hunting and predictions of future climate change.

After decades of hard hunting and environmental contamination by toxins such as PCBs, there were only 5,000 grey seals left in the entire Baltic Sea by the 1970s, falling from an initial size of more than 90,000 at the ...

Small Aussie mammal's bite 'packs a punch'

2024-03-27

Australian rock-wallabies are ‘little Napoleons’ when it comes to compensating for small size, packing much more punch into their bite than larger relatives.

Researchers from Flinders University made the discovery while investigating how two dwarf species of rock-wallaby are able to feed themselves on the same kinds of foods as their much larger cousins.

Study leader Dr Rex Mitchell also coined the idea of ‘Little Wallaby Syndrome’ after examining the skulls of dwarf rock-wallabies to discover they can more than compensate for their size.

“We already knew that ...

Advancing towards sustainability: turning carbon dioxide and water into acetylene

2024-03-27

Reaching sustainability is one of humanity’s most pressing challenges today—and also one of the hardest. To minimize our impact on the environment and start reverting the damage humanity has already caused, striving to achieve carbon neutrality in as many economic activities as possible is paramount. Unfortunately, the synthesis of many important chemicals still causes high carbon emissions.

Such is the case of acetylene (C2H2), an essential hydrocarbon with a plethora of applications. This highly ...

Twist of groundwater contaminants

2024-03-27

In recent years, the world has been experiencing floods and droughts as extreme rainfall events have become more frequent due to climate change. For this reason, securing stable water resources throughout the year has become a national responsibility called 'water security', and 'Aquifer Storage Recovery (ASR)', which stores water in the form of groundwater in the ground when water resources are available and withdraws it when needed, is attracting attention as an effective water resource management technique.

The Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) announced that a team of Dr. Seunghak ...

Scientists extract genetic secrets from 4,000-year-old teeth to illuminate the impact of changing human diets over the centuries

2024-03-27

Researchers at Trinity College Dublin have recovered remarkably preserved microbiomes from two teeth dating back 4,000 years, found in an Irish limestone cave. Genetic analyses of these microbiomes reveal major changes in the oral microenvironment from the Bronze Age to today. The teeth both belonged to the same male individual and also provided a snapshot of his oral health.

The study, carried out in collaboration with archaeologists from the Atlantic Technological University and University ...

Treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer with driver mutations

2024-03-27

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. Improved understanding of driver mutations of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has led to more biomarker-directed treatment for patients with advanced stages. The expanding number of drugs targeting these driver mutations offers more opportunity to improve patient’s survival benefit.

To date, NSCLCs, especially those with non-squamous histology, are recommended for testing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene rearrangements, ROS proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase 1 (ROS-1) rearrangements, B-raf proto-oncogene (BRAF) mutations, rearranged during transfection ...

UK rabbit owners can recognize pain in their pets, study finds

2024-03-27

Rabbits are popular family pets, with around 1.5 million* in the UK and it is important that owners can recognise when their animal is in pain, and know when to seek help to protect their rabbit’s welfare. New research by the University of Bristol Veterinary School has found the majority of rabbit owners could list signs of pain and could mostly identify pain-free rabbits and those in severe pain, but many lacked knowledge of the subtler sign of pain.

The study, published in BMC Veterinary Research today [27 March], provides the first insight into how rabbit owners identify pain and their general ability to apply this knowledge to detect pain ...

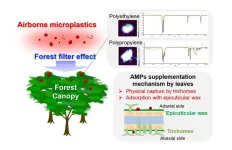

World's first demonstration that forests trap airborne microplastics

2024-03-27

A research group led by Japan Women’s University finds that airborne microplastics adsorb to the epicuticular wax on the surface of forest canopy leaves, and that forests may act as terrestrial sinks for airborne microplastics

Tokyo, Japan – Think of microplastics, and you might think of the ones accumulating in the world’s oceans. However, they are also filling the sky and the air we breathe. Now, it has been discovered that forests might be acting as a sink for these airborne microplastics, offering humanity yet another ...

How will you age? World-leading Dunedin Study launches next phase

2024-03-27

The world-leading Dunedin Study is set to launch its age 52 assessments, delving into an understudied but important period of life and time of change.

The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study is a longitudinal study that follows the lives of 1037 babies born in Queen Mary Maternity Hospital between 1 April 1972 and 31 March 1973. It is the most detailed study of human health and development in the world.

Members have been assessed regularly throughout their lives, most recently at age 45.

Study Director, Research Professor Moana Theodore is incredibly excited ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

[Press-News.org] Scientists discover how caterpillars can stop their bleeding in secondsInsect blood has ‘extraordinary ability’ to change its material properties, and may help develop new drugs for humans