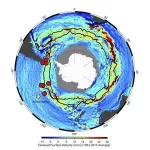

(Press-News.org) It carries more than 100 times as much water as all the world's rivers combined. It reaches from the ocean's surface to its bottom, and measures as much as 2,000 kilometers across. It connects the Indian, Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and plays a key role in regulating global climate. Continuously swirling around the southernmost continent, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current is by far the world's most powerful and consequential mover of water. In recent decades it has been speeding up, but scientists have been unsure whether that is connected to human-induced global warming, and whether the current might offset or amplify some of warming's effects.

In a new study, an international research team used sediment cores from the planet's roughest and most remote waters to chart the ACC's relationship to climate over the last 5.3 million years. Their key discovery: During past natural climate swings, the current has moved in tandem with Earth's temperature, slowing down during cold times and gaining speed in warm ones―speedups that abetted major losses of Antarctica's ice. This suggests that today's speedup will continue as human-induced warming proceeds. That could hasten the wasting of Antarctica's ice, increase sea levels, and possibly affect the ocean's ability to absorb carbon from the atmosphere.

The findings were just published in the journal Nature.

"This is the mightiest and fastest current on the planet. It is arguably the most important current of the Earth climate system," said study coauthor Gisela Winckler, a geochemist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory who co-led the sediment sampling expedition. The study "implies that the retreat or collapse of Antarctic ice is mechanistically linked to enhanced ACC flow, a scenario we are observing today under global warming," she said.

The conditions for the ACC were set about 34 millions years ago, after tectonic forces separated Antarctica from other continental masses further north and the ice sheets began building up; the current is thought to have started flowing in its modern form 12 million to 14 million years ago. Driven by continuous westerly winds, and with no land in the way, it circles Antarctica clockwise (as seen from the bottom of the Earth) at about 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) per hour, carrying 165 million to 182 million cubic meters of water each second.

Scientists have observed that winds over the Southern Ocean have increased in strength about 40% in past 40 years. Among other things, this has speeded the ACC and energized large-scale eddies within it that move relatively warm waters from the higher latitudes toward Antarctica's huge floating ice shelves, which hold back the even vaster interior glaciers. In parts of Antarctica, especially in the west, these warm waters are eating the undersides of the ice shelves―the main reason they are wasting, not warming air temperatures.

"If you leave an ice cube out in the air, it takes quite a while to melt," said Winckler. "If you put it in contact with warm water, it goes rapidly."

"This loss of ice can be attributed to increased heat transport to the south," said the study's lead author, Frank Lamy, of Germany's Alfred Wegener Institute. "A stronger ACC means more warm, deep water reaches the ice-shelf edge of Antarctica."

Through a complex set of processes, the ocean waters ringing Antarctica also currently absorb about 40% of the carbon that humans introduce into the atmosphere. It is unclear whether the speedup of the ACC will compromise this, but some scientists fear it will.

The study involved some 40 scientists from a dozen countries. At sea, aboard the drill ship JOIDES Resolution, researchers gathered ocean-floor sediment underlying the ACC near Point Nemo—the spot in the far southwestern Pacific that is farthest from land anywhere, some 2,600 kilometers from even the tiny Pitcairn Islands. The two-month cruise took place from May to July 2019, during the violent austral winter, when there was little daylight and waves as high as 20 meters threatened the ship.

The ship's crew dropped a drill string some 3,600 meters from the ocean surface to the ocean floor. They then penetrated the floor and removed thin sediment cores measuring 150 and 200 meters each. Using an advanced X-ray technique, the scientists later analyzed layers built up over millions of years. Since smaller particles tend to settle during times when the current is sluggish and larger ones when it is fast, they were able to chart scores of changes in the ACC's speed over time. Compared to the mean flow over the last 12,000 years―the period since the last ice age encompassing the development of human civilization―flows dropped by as much half during cold times, and at times nearly doubled during warm ones.

Using previous studies of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, they correlated fast-flow periods with repeated bouts of ice retreat. These were punctuated by colder times, when glaciers advanced. The warmest extended period of the 5.3-million year record was during the Pliocene, which ended about 2.4 million years ago. After that came a period called the Pleistocene, when dozens of chilly glacial periods alternated with so-called interglacials, when temperatures rose, the current speeded up and the ice pulled back. Currently much of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is frozen to land that is below sea level, so it is highly susceptible to invasion by warm ocean waters. Were it to melt entirely, it would raise global sea levels by about 190 feet.

"These findings provide geological evidence in support of further increasing ACC flow with continued global warming," the researchers write in their paper. "If true, a future increase in ACC flow with warming climate would mark a continuation of the pattern observed in instrumental records, with likely negative consequences."

# # #

Scientist contacts:

Gisela Winckler: winckler@ldeo.columbia.edu

Frank Lamy: frank.lamy@awi.de

More information: Kevin Krajick, Senior editor, science news, Columbia Climate School/Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory kkrajick@ei.columbia.edu 917-361-7766

END

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current plays an important part in global overturning circulation, the exchange of heat and CO2 between the ocean and atmosphere, and the stability of Antarctica’s ice sheets. An international research team led by the Alfred Wegener Institute and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory have now used sediments taken from the South Pacific to reconstruct the flow speed in the last 5.3 million years. Their data show that during glacial periods, the current slowed; during interglacials, it accelerated. Consequently, if ...

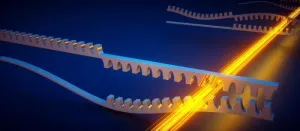

Researchers at AMOLF, in collaboration with partners from Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, have realized a new type of metamaterial through which sound waves flow in an unprecedented fashion. It provides a novel form of amplification of mechanical vibrations, which has the potential to improve sensor technology and information processing devices. This metamaterial is the first instance of a so-called ‘bosonic Kitaev chain’, which gets its special properties from its nature as a topological material. It was realized by making nanomechanical resonators interact with laser light through radiation pressure forces. The discovery, which is published on March ...

March 27, 2024—(BRONX, NY)—Just as you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs, scientists at Albert Einstein College of Medicine have found that you can’t make long-term memories without DNA damage and brain inflammation. Their surprising findings were published online today in the journal Nature.

“Inflammation of brain neurons is usually considered to be a bad thing, since it can lead to neurological problems such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease,” said study leader Jelena Radulovic, M.D., Ph.D., professor in the Dominick P. Purpura Department of Neuroscience, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, and the Sylvia ...

Anastasopoulos Studying Machine Translation For Austronesian Languages

Antonios Anastasopoulos, Assistant Professor, Computer Science, received funding for: "Machine Translation for Austronesian Languages."

He is helping to develop a solution that can automatically translate languages of the southeast Asia and Pacific regions, with a particular focus on languages of lndonesia and the Philippines.

Anastasopoulos received $63,680 from Barron Associates, Inc., on a subaward from the U.S. Department of the Army for this project. Funding began ...

The first comprehensive reference genome for ‘R570’, a widely cultivated modern sugarcane hybrid, has been completed in a landmark advancement for agricultural biotechnology.

Sugarcane contributes $2.2 billion to the Australian economy and accounts for 80 per cent of global sugar supply. The mapping of its genetic blueprint opens opportunities for new tools to enhance breeding programs around the world for this valuable bioenergy and food crop.

It is one of the last major crops to be fully sequenced, due to the fact its genome is almost three times the size of humans’ and far more ...

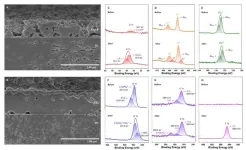

Super wearable electronics that are lightweight, stretchable and increase sweat permeability by 400-fold have been developed by scientists at City University of Hong Kong (CityUHK), enabling reliable long-term monitoring of biosignals for biomedical devices.

Led by Professor Yu Xinge in CityUHK’s Department of Biomedical Engineering (BME), the research team has recently developed a universal method to creating these super wearable electronics that allow gas and sweat permeability, solving the most critical issue facing wearable biomedical devices.

Wearable ...

They published their work on Mar. 20, 2024, in Energy Material Advances.

"TR poses a critical safety concern for HED LIBs," said paper author Jiantao Wang, the general manager of National Power Battery Innovation Center, the general manager of China Automotive Battery Research Institute Co., Ltd, professor in General Research Institute for Nonferrous Metals. "It hinders HED LIBs wide application in electric vehicles."

Wang explained that TR can occur during various ...

People who can’t visualise an image in their mind’s eye are less likely to remember the details of important past personal events or to recognise faces, according to a review of nearly ten years of research.

People who cannot bring to mind visual imagery are also less likely to experience imagery of other kinds, like imagining music, according to new research by the academic who first discovered the phenomenon.

Professor Adam Zeman, of the University of Exeter, first coined the term aphantasia in 2015, to describe those who can’t visualise. ...

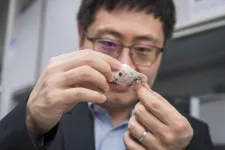

From pacemakers to neurostimulators, implantable medical devices rely on batteries to keep the heart on beat and dampen pain. But batteries eventually run low and require invasive surgeries to replace. To address these challenges, researchers in China devised an implantable battery that runs on oxygen in the body. The study, published March 27 in the journal Chem, shows in rats that the proof-of-concept design can deliver stable power and is compatible with the biological system.

“When you think about it, oxygen is the source of our life,” says corresponding author Xizheng Liu, who specializes in energy materials and devices at Tianjin University of Technology. “If ...

Researchers Toru Miyamoto, Ko Mochizuki, and Atsushi Kawakita of the University of Tokyo have discovered the first species pollinated by sap beetles in the genus Pandanus, a group of palm-like plants native to the tropics and subtropics of Africa and Eurasia. The discovery overturned the long-held belief that these plants were pollinated by wind. The researchers also found that fragrant screw pines’ male and female flowers produced heat at night stably, making them the first such species in the family Pandanaceae. The findings were published in ...