(Press-News.org) A new study led by Michigan State University researcher Peter Williams sheds light on the profound influence of deep geographic isolation on the evolution of mammals. Published in Nature Communications on March 28, the research reveals how long-lasting separation between continents has shaped distinct mammal communities around the globe.

“Today’s ecology was not inevitable. If there were different isolating factors long ago, we might have vastly different ecosystems today,” said Peter Williams, the lead author of the study. Williams is a research associate in the Integrative Biology department and a postdoctoral researcher in MSU’s Ecology, Evolution and Behavior program, or EEB.

While environmental factors like climate and vegetation are well-known drivers of biodiversity, the new study highlights the crucial role that isolation played for mammals.

“Think tree-dwelling mammals,” Williams said. “Despite similar climates, you’ll find koalas in Australia and squirrels in Spain.”

What you won’t find, however, are koalas native to Spain or squirrels native to Australia.

“That distinction stems from deep-seated geographic isolation and diverging evolutionary paths long ago,” Williams said.

With this new perspective, the findings of this research don’t just satisfy curiosity about that natural world. The report holds significant implications for conservation efforts and modern ecological issues.

“By understanding how historical isolation has shaped biodiversity, we can gain valuable insights into the delicate balance of ecosystems and develop strategies for protecting biodiversity in regions with unique evolutionary histories,” Williams said.

“In ecology, even hyperlocal problems need to incorporate regional, continental or even global processes — weather patterns, ocean currents or, in this case, deep-seated geographic barriers,” said Elise Zipkin, co-author of the study and associate professor of integrative biology. She’s also the leader of the Zipkin Quantitative Ecology Lab and director of EEB. “They all impact today’s natural world.”

Deep isolation shapes mammal evolution

Supported by the National Science Foundation, the study uses a novel approach to analyze biogeographic isolation, incorporating a continuous measure called “phylobetadiversity,” which quantifies shared evolutionary history, Williams said.

For instance, phylobetadiversity would be low when comparing Michigan with somewhere in Europe that’s also home to deer, rabbits, squirrels and the like, he said.

“Even if they aren't the same species, there is a lot of shared evolutionary history at the community level,” Williams said.

Michigan and Australia would be at the opposite end of the phylobetadiversity spectrum.

“Australia has mostly marsupials, while in Michigan we don't have any marsupials except the opossum,” he continued. “There is very little shared evolutionary history at the community level.”

Using phylobetadiversity paints a nuanced picture of how connected different regions have been historically.

“Isolated regions like Australia and Madagascar harbor mammal assemblages that are much less diverse than expected based on environment alone and those mammals possess unique combinations of functional traits, reflecting the distinct evolutionary paths they’ve taken,” Williams said. “It’s a fascinating idea that the biodiversity patterns we see in today’s world were not inevitable.”

The key factor in biodivergence for isolated mammals seems to be the duration of isolation.

Regions like Australia, isolated for 30-35 million years, have had ample time for unique mammal lineages to evolve. In contrast, continents like North and South America, which were once separated but reconnected during the Great American Biotic Interchange 2.7 million years ago, show more convergence in their mammal communities, with similar climates selecting for similar functional traits.

Though the evolution of mammals was heavily impacted by the isolation of land masses, the study shows birds reacted quite differently.

Birds, with their greater ability to fly across vast distances, can more easily overcome geographic barriers. This constant movement and mixing of bird populations across continents has led to a homogenization of bird communities globally, with environmental factors playing a stronger role in shaping their diversity.

Interestingly, bats told a completely different story. As the only flying mammal group, bats in the Western Hemisphere, such as vampire bats and fish-eating bats, exhibit a much higher degree of functional diversity compared with their counterparts in the Eastern Hemisphere. This, the researchers suggest, is likely a consequence of their independent evolutionary trajectories shaped by the long-standing separation of landforms in the different regions.

Unlike other mammals, most bats didn’t have the cold tolerance to traverse the Beringia land bridge that, long ago, connected Alaska and Siberia, leading to their continued isolation and modern divergent species across hemispheres.

The team at the Zipkin lab aims to continue this line of research, conducting additional studies to look further into mammalian histories and how biogeographic divides have shaped the biota on our planet.

“This is just the beginning of our journey toward a deeper understanding of the world around us,” Zipkin said.

END

Ancient isolation’s impact on modern ecology

Michigan State researchers show deep biogeographic divides drive divergent evolutionary paths

2024-03-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

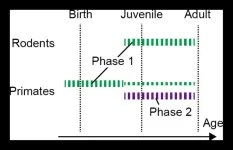

Synaptic protein change during development offers clues on evolution and disease

2024-03-28

The first analysis of how synaptic proteins change during early development reveals differences between mice and marmosets but also what's different in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. The Kobe University findings offer first insights into the mechanism behind synaptic development and open up routes for research on possible treatments.

Given that synapses are the connections between our brain cells, one might think that having as many of these as possible is a good thing. However, primate brains do something unexpected: After early childhood, ...

How commercial rooftop solar power could bring affordable clean energy to low-income homes

2024-03-28

Lower-income communities across the United States have long been much slower to adopt solar power than their affluent neighbors, even when local and federal agencies offer tax breaks and other financial incentives.

But, commercial and industrial rooftops, such as those atop retail buildings and factories, offer a big opportunity to reduce what researchers call the “solar equity gap,” according to a new study, published in Nature Energy and led by researchers at Stanford University.

“The ...

Taking a closer look at pulmonary fibrosis genetics

2024-03-28

PHOENIX, Ariz. — March 28, 2024 — Regulators of gene expression are thought to play an outsized role in disorders from cancers to heart disease. But how exactly do variations in gene regulation translate into a disease’s biology?

A team of scientists led by researchers from the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), part of the City of Hope, together with investigators at St. Vincent’s Institute of Medical Research and Vanderbilt University Medical Center, now have a better answer for this question when it comes to pulmonary fibrosis (PF), an incurable respiratory disease.

Their study, published today in Nature Genetics, is the first to look at these ...

Cats with MDR1 mutation at risk of severe reactions to popular medication

2024-03-28

PULLMAN, WA -- More than half a million cats in the United States could be at risk of a severe or even fatal neurological reaction to the active ingredient in some top-selling parasite preventatives for felines.

While the ingredient, eprinomectin, which is found in products like NexGard COMBO and Centragard, appears safe and effective for the significant majority of cats when used at label doses, a study conducted by Washington State University’s Program for Individualized Medicine identified a risk of severe adverse effects in cats with the ...

IOP Publishing and IPEM mandate reporting of sex and gender in research

2024-03-28

IOP Publishing (IOPP) and the Institute of Physics and Engineering (IPEM) have introduced checks for sex and gender equality for all manuscripts submitted to their jointly published journal Physiological Measurement.

In line with the Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) guidelines, which were introduced to ensure that sex and gender considerations are appropriately reported in scholarly literature, all research published in Physiological Measurement must declare the sex and gender balance of subject groups. Authors are ...

Dogs trained to detect trauma stress by smelling humans’ breath

2024-03-28

Dogs’ sensitive noses can detect the early warning signs of many potentially dangerous medical situations, like an impending seizure or sudden hypoglycemia. Now, scientists have found evidence that assistance dogs might even be able to sniff out an oncoming PTSD flashback, by teaching two dogs to alert to the breath of people who have been reminded of traumas.

“PTSD service dogs are already trained to assist people during episodes of distress,” said Laura Kiiroja of Dalhousie University, first author of the paper ...

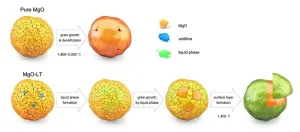

Electronic device thermal management made simpler and slightly better!

2024-03-28

Dr. Cheol-Woo Ahn, leading a research team at the Department of Functional Ceramics within the Ceramic Materials Division at the Korea Institute of Materials Science(KIMS), has developed the world's first heat dissipation material. This material reduces hydrophilicity through a chemical reaction that forms a nanocrystalline composite layer and increases thermal conductivity by controlling point defects. This process occurs during a simple sintering process that does not require surface treatment. KIMS is a government-funded research institute under the Ministry of Science and ICT.

Conventional ...

Study: Dangerous surgical site infections can be reduced with simple prevention protocol

2024-03-28

Arlington, Va. — March 28, 2024 — A new study published today in the American Journal of Infection Control (AJIC) demonstrates the use of a simple pre-surgical infection prevention protocol to prevent dangerous post-surgical infections. Researchers performed this investigation at the Soroka University Medical Center in Israel.

Surgical site infections (SSIs) are a type of healthcare-associated infection with deadly consequences for some patients. According to the latest data from the Centers for ...

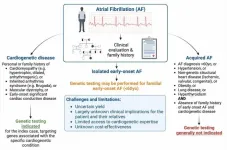

Genetic testing of patients with atrial fibrillation can alert clinicians to potential development of life-threatening conditions

2024-03-28

Philadelphia, March 28, 2024 – Although the vast majority of clinicians do not view atrial fibrillation (AF) as a genetic disorder, a White Paper in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology, published by Elsevier, analyzes the current understanding of genetics and the role of genetic testing in AF and concludes there is an increasing appreciation that genetic culprits for potentially life-threatening ventricular cardiomyopathies and channelopathies may initially present with AF.

AF is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia and is associated with increased risks of heart failure, stroke, and death. It is ...

Artificial Intelligence tool successfully predicts fatal heart rhythm

2024-03-28

In a Leicester study that looked at whether artificial intelligence (AI) can be used to predict whether a person was at risk of a lethal heart rhythm, an AI tool correctly identified the condition 80 per cent of the time.

The findings of the study, led by Dr Joseph Barker working with Professor Andre Ng, Professor of Cardiac Electrophysiology and Head of Department of Cardiovascular Sciences at the University of Leicester and Consultant Cardiologist at the University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, have been published in the European Heart Journal – Digital Health.

Ventricular arrhythmia (VA) is a heart rhythm disturbance originating from the bottom chambers (ventricles) where ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

USC study reveals differences in early Alzheimer’s brain markers across diverse populations

300 million years of hidden genetic instructions shaping plant evolution revealed

High-fat diets cause gut bacteria to enter brain, Emory study finds

Teens and young adults with ADHD and substance use disorder face treatment gap

Instead of tracking wolves to prey, ravens remember — and revisit — common kill sites

Ravens don’t follow wolves to dinner – they remember where the food is

Mapping the lifelong behavior of killifish reveals an architecture of vertebrate aging

Designing for hard and brittle lithium needles may lead to safer batteries

Inside the brains of seals and sea lions with complex vocal behavior learning

Watching a lifetime in motion reveals the architecture of aging

Rapid evolution can ‘rescue’ species from climate change

Molecular garbage on tumors makes easy target for antibody drugs

New strategy intercepts pancreatic cancer by eliminating microscopic lesions before they become cancer

Embryogenesis in 4D: a developmental atlas for genes and cells

CNIO research links fertility with immune cells in the brain

Why do lithium-ion batteries fail? Scientists find clues in microscopic metal 'thorns'

Surface treatment of wood may keep harmful bacteria at bay

Carsten Bönnemann, MD, joins St. Jude to expand research on pediatric catastrophic neurological disorders

Women use professional and social networks to push past the glass ceiling

Trial finds vitamin D supplements don’t reduce covid severity but could reduce long COVID risk

Personalized support program improves smoking cessation for cervical cancer survivors

Adverse childhood experiences and treatment-resistant depression

Psilocybin trends in states that decriminalized use

New data signals high demand in aesthetic surgery in southern, rural U.S. despite access issues

$3.4 million grant to improve weight-management programs

Higher burnout rates among physicians who treat sickle cell disease

Wetlands in Brazil’s Cerrado are carbon-storage powerhouses

Brain diseases: certain neurons are especially susceptible to ALS and FTD

Father’s tobacco use may raise children’s diabetes risk

Structured exercise programs may help combat “chemo brain” according to new study in JNCCN

[Press-News.org] Ancient isolation’s impact on modern ecologyMichigan State researchers show deep biogeographic divides drive divergent evolutionary paths