(Press-News.org) UVA Health researchers have discovered a potential explanation for some of the most perplexing mysteries of COVID-19 and long COVID. The surprising findings could lead to new treatments for the difficult acute effects of COVID-19, long COVID and possibly other viruses.

Researchers led by UVA’s Steven L. Zeichner, MD, PhD, found that COVID-19 may prompt some people’s bodies to make antibodies that act like enzymes that the body naturally uses to regulate important functions – blood pressure, for example. Related enzymes also regulate other important body functions, such as blood clotting and inflammation.

Doctors may be able to target these “abzymes” to stop their unwanted effects. If abzymes with rogue activities are also responsible for some of the features of long COVID, doctors could target the abzymes to treat the difficult and sometimes mysterious symptoms of COVID-19 and long COVID at the source, instead of merely treating the downstream symptoms.

“Some patients with COVID-19 have serious symptoms and we have trouble understanding their cause. We also have a poor understanding of the causes of long COVID,” said Zeichner, a pediatric infectious disease expert at UVA Children’s. “Antibodies that act like enzymes are called ‘abzymes.’ Abzymes are not exact copies of enzymes and so they work differently, sometimes in ways that the original enzyme does not. If COVID-19 patients are making abzymes, it is possible that these rogue abzymes could harm many different aspects of physiology. If this turns out to be true, then developing treatments to deplete or block the rogue abzymes could be the most effective way to treat the complications of COVID-19.”

Understanding COVID-19 Abzymes

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID, has protein on its surface called the Spike protein. When the virus begins to infect a cell, the Spike protein binds a protein called Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2, or ACE2, on the cell’s surface. ACE2’s normal function in the body is to help regulate blood pressure; it cuts a protein called angiotensin II to make a derivative protein called angiotensin 1-7. Angiotensin II constricts blood vessels, raising blood pressure, while angiotensin 1-7 relaxes blood vessels, lowering blood pressure.

Zeichner and his team thought that some patients might make antibodies against the Spike protein that looked enough like ACE2 so that the antibodies also had enzymatic activity like ACE2, and that is exactly what they found.

Recently, other groups have found that some patients with long COVID have problems with their coagulation systems and with another system called “complement.” Both the coagulation system and the complement system are controlled by enzymes in the body that cut other proteins to activate them. If patients with long COVID make abzymes that activate proteins that control processes such as coagulation and inflammation, that could explain the source of some of the long COVID symptoms and why long COVID symptoms persist even after the body has cleared the initial infection. It also may explain rare side effects of COVID-19 vaccination.

To determine if antibodies could be having unexpected effects in COVID patients, Zeichner and his collaborators examined plasma samples collected from 67 volunteers with moderate or severe COVID on or around day 7 of their hospitalization. The researchers compared what they found with plasma collected in 2018, prior to the beginning of the pandemic. The results showed that a small subset of the COVID patients had antibodies that acted like enzymes.

While our understanding of the potential role of abzymes in COVID-19 is still in its early stages, enzymatic antibodies have already been detected in certain cases of HIV, Zeichner notes. That means there is precedent for a virus to trigger abzyme formation. It also suggests that other viruses may cause similar effects.

Zeichner, who is developing a universal coronavirus vaccine, expects UVA’s new findings will renew interest in abzymes in medical research. He also hopes his discovery will lead to better treatments for patients with both acute COVID-19 and long COVID.

“We now need to study pure versions of antibodies with enzymatic activity to see how abzymes may work in more detail, and we need to study patients who have had COVID-19 who did and did not develop long COVID,” he said. “There is much more work to do, but I think we have made a good start in developing a new understanding of this challenging disease that has caused so much distress and death around the world. The first step to developing effective new therapies for a disease is developing a good understanding of the disease’s underlying causes, and we have taken that first step.”

Findings Published

The researchers have published their findings in the scientific journal mBio, a publication of the American Society for Microbiology. The research team consisted of Yufeng Song, Regan Myers, Frances Mehl, Lila Murphy, Bailey Brooks, and faculty members from the Department of Medicine, Jeffrey M. Wilson, Alexandra Kadl, Judith Woodfolk.

“It’s great to have such talented and dedicated colleagues here at UVA who are excited about working on new and unconventional research projects,” said Zeichner.

Zeichner is the McClemore Birdsong Professor in the University of Virginia School of Medicine’s Departments of Pediatrics and Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer Biology; the director of the Pendleton Pediatric Infectious Disease Laboratory; and part of UVA Children’s Child Health Research Center.

The abzyme research was supported by UVA, including the Manning Fund for COVID-19 Research at UVA; the Ivy Foundation; the Pendleton Laboratory Fund for Pediatric Infectious Disease Research; a College Council Minerva Research Grant; the Coulter Foundation; and the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infection Diseases, grant R01 AI176515. Additional support came from the HHV-6 Foundation.

To keep up with the latest medical research news from UVA, subscribe to the Making of Medicine blog at http://makingofmedicine.virginia.edu.

END

COVID-19 antibody discovery could explain long COVID

2024-03-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Wild plants face viral surprise

2024-03-28

Just as many people battle seasonal colds and flu, native plants face their own viral threats. People have long known that plants can succumb to viruses just like humans. Now, a new study led by Michigan State University and the University of California, Riverside reveals a previously unknown threat: non-native crop viruses are infecting and jeopardizing the health of wild desert plants.

“For years, the ecological field assumed wild plants were immune to invasive viruses that damage crops,” said Carolyn ...

Storing electrons from hydrogen for clean chemical reactions

2024-03-28

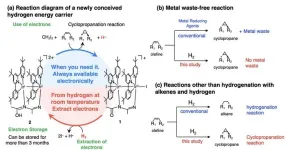

Fukuoka, Japan—Researchers from Kyushu University have developed a hydrogen energy carrier to address some of the biggest hurdles in the path towards a sustainable hydrogen economy. As explained in a paper published in JACS Au, this novel compound can efficiently “store electrons” from hydrogen in a solid state to use in chemical reactions later.

Hydrogen is a promising source of clean energy with a lot of untapped potential applications in industry and everyday life. Unlike conventional fuels, hydrogen can be used to generate electricity without producing greenhouse ...

Unlocking how to use mRNA to target Alzheimer’s disease

2024-03-28

Scientists at The Florey have developed an mRNA technology approach to target the toxic protein tau, which builds up in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

To date, mRNA has been predominantly used for vaccines, including those used to fight COVID-19.

New research published today in Brain Communications establishes The Florey as a key player in the mRNA field, with Dr Rebecca Nisbet taking the technology in a new direction.

“This is the first time mRNA has been explored for use in Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr Nisbet said. “Our work in cell models demonstrates that this technology ...

Kessler Foundation secures $770,000 in grants to advance leading-edge spinal cord research

2024-03-28

East Hanover, NJ – March 28, 2024 – Kessler Foundation received two grants from The New Jersey Commission on Spinal Cord Research that will fuel innovative research in the field of spinal cord injury (SCI). These grants will fund efforts aimed at improving the cognitive assessment of individuals with traumatic SCI and pilot-testing the first-of-its-kind Spinal Cord Injury Personal Assistance Services Survey (SCI-PASS).

Traumatic spinal cord injury (tSCI) often leads to cognitive impairment, affecting up to 60 percent of individuals living with this condition. “The challenge lies in assessing cognitive functions in people with tSCI, as many existing tests rely on upper limb ...

Going ‘back to the future’ to forecast the fate of a dead Florida coral reef

2024-03-28

Rising temperatures and disease outbreaks are decimating coral reefs throughout the tropics. Evidence suggests that higher latitude marine environments may provide crucial refuges for many at-risk, temperature-sensitive coral species. However, how coral populations expand into new areas and sustain themselves over time is constrained by the limited scope of modern observations.

What can thousands of years of history tell us about what lies ahead for coral reef communities? A lot. In a new study, Florida Atlantic University researchers and collaborators provide geological insights into coral range expansions by reconstructing the composition of a Late Holocene-aged subfossil coral ...

How extratropical ocean-atmosphere interactions can contribute to the variability of jet streams in the Northern Hemisphere

2024-03-28

Fukuoka, Japan—The interaction between the oceans and the atmosphere plays a vital role in shaping the Earth’s climate. Changing sea surface temperatures can heat or cool the atmosphere, and changes in the atmosphere can do the same to the ocean surface. This exchange in energy is known as “ocean-atmosphere coupling.”

Now, researchers from Kyushu University have revealed that this ocean-atmosphere coupling enhances teleconnection patterns—when climate conditions change across vast regions of the globe—in the Northern Hemisphere. In their recent ...

MSK Research Highlights, March 28, 2024

2024-03-28

Low recurrence seen with cryoablation for large breast tumors

Cryoablation, a minimally invasive technique used to freeze and destroy small tumors, is effective for breast cancer patients with larger tumors, according to research presented by MSK interventional radiologist Yolanda Bryce, MD, at the 2024 Society of Interventional Radiology Annual Scientific Meeting.

The retrospective study assessed outcomes for 60 patients who underwent cryoablation because they were not candidates for surgery or declined surgery due to other health concerns. The average size of their tumors was 2.5 centimeters. In a follow-up after 16 months, only 10% of patients experienced a recurrence ...

USDA, Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College collaborate to support Indigenous Seed Sovereignty

2024-03-28

MANDAN, N.D., March 28, 2024—The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Agricultural Research Service (ARS) announces a cooperative agreement with the Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish (NHS) College to conduct research supporting Indigenous Seed Sovereignty. This collaborative effort will increase the number of traditional varieties of seeds of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara (MHA) Nation crops within NHS College's traditional seed cache.

This agreement builds upon USDA’s strengthened partnerships with ...

For younger women, mental health now may predict heart health later

2024-03-28

Younger women are generally thought to have a low risk of heart disease, but new research urges clinicians to revisit that assumption, especially for women who suffer from certain mental health conditions. A new study being presented at the American College of Cardiology’s Annual Scientific Session found that having anxiety or depression could accelerate the development of cardiovascular risk factors among young and middle-aged women.

The study draws new attention to the importance of cardiovascular screening and preventive care as rates of cardiovascular risk factors rise and heart attacks become more common in younger people. Anxiety and depression ...

Missed opportunity: AEDs near cardiac arrests rarely used by bystanders

2024-03-28

Automated external defibrillators (AEDs) are a common resource in public buildings, yet a new analysis reveals that they are rarely used to help resuscitate people suffering cardiac arrest. Research, which will be presented at the American College of Cardiology’s Annual Scientific Session, found that AEDs were only used in 13 of nearly 1,800 cases of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, even though many of the incidents occurred near a public AED.

Cardiac arrest occurs when the heart suddenly stops beating. It is different from a heart attack, which is when a blockage prevents blood ...