(Press-News.org) Scientists at King’s College London have discovered a new cause for asthma that sparks hope for treatment that could prevent the life-threatening disease.

Most current asthma treatments stem from the idea that it is an inflammatory disease. Yet, the life-threatening feature of asthma is the attack or the constriction of airways, making breathing difficult. The new study, published today in Science, shows for the first time that many features of an asthma attack—inflammation, mucus secretion, and damage to the airway barrier that prevents infections - result from this mechanical constriction in a mouse model.

The findings suggest that blocking a process that normally causes epithelial cell death could prevent the damage, inflammation, and mucus that result from an asthma attack.

Professor Jody Rosenblatt from King’s College London said: “Our discovery is the culmination of more than ten years work. As cell biologists who watch processes, we could see that the physical constriction of an asthma attack causes widespread destruction of the airway barrier. Without this barrier, asthma sufferers are far more likely to get long-term inflammation, wound healing, and infections that cause more attacks. By understanding this fundamental mechanism, we are now in a better position to prevent all these events.”

In the UK, 5.4 million people have asthma and can suffer from symptoms such as wheezing, coughing, feeling breathlessness and a tight chest. Triggers such as pollen or dust can make asthma symptoms worse and can lead to a life-threatening asthma attack.

Despite the disease commonality, the causes of asthma are still not understood. Current medications treat the consequences of an asthma attack by opening the airways, calming inflammation, and breaking up the sticky mucus which clogs the airway, which help control asthma, but do not prevent it.

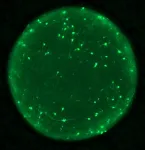

The answer to stopping asthma symptoms may lie in cell extrusion, a process the researchers discovered that drives most epithelial cell death. Scientists used mouse lung models and human airway tissue to discover that when the airways contract, known as bronchoconstriction, the epithelial cells that line the airway get squeezed out to later die.

Because bronchoconstriction causes so many cell extrusions, it damages the airway barrier which causes inflammation and excess mucus.

In previous studies, the scientists found that the chemical compound gadolinium can block extrusion. In this study, they found it could work in mice to prevent the excess extrusion that causes damage and inflammation after an asthma attack. The authors note that gadolinium has not been tested in humans and has not been deemed to be safe or efficacious.

Professor Rosenblatt said: “This constriction and destruction of the airways causes the post-attack inflammation and excess mucus secretion that makes it difficult for people with asthma to breathe.

“Current therapies do not prevent this destruction – an inhaler such as Albuterol opens the airways, which is critical to breathing but, dishearteningly, we found it does not prevent the damage and the symptoms that follow an attack. Fortunately, we found that we can use an inexpensive compound, gadolinium which is frequently used for MRI imaging, to stop the airway damage in mice models as well as the ensuing inflammation and mucus secretion. Preventing this damage could then prevent the build-up of musculature that cause future attacks.”

Professor Chris Brightling from the University of Leicester and one of the co-authors of the study said: “In the last decade there has been tremendous progress in therapies for asthma particularly directed towards airway inflammation. However, there remains ongoing symptoms and attacks in many people with asthma. This study identifies a new process known as epithelial extrusion whereby damage to the lining of the airway occurs as a consequence of mechanical constriction and can drive many of the key features of asthma. Better understanding of this process is likely to lead to new therapies for asthma.”

Dr Samantha Walker, Director of Research and Innovation at Asthma + Lung UK, said: “Only two per cent of public health funding is allocated to developing new treatments for the 12 million people living with lung conditions in the UK so new research that can help in the treatment or prevention of asthma is good news. (1)

“This research using an experimental mouse model shows that constricting the airways leads to damage to the lung lining and inflammation, like that seen in asthma. It is this constriction and resulting damage that makes it difficult for people with asthma to breathe.

“Current medications for asthma work by treating the inflammation, but this isn’t effective for everyone. Treatments aim to prevent future asthma attacks and improve asthma control by taking inhalers every day, but we know that ~31 per cent of people with asthma don't have treatment options that work for them, putting them at risk of potentially life-threatening asthma attacks. (2)

“This discovery opens important new doors to explore possible new treatment options desperately needed for people with asthma rather than focusing solely on inflammation.” (3)

The discovery of the mechanics behind cell extrusion could underlie other inflammatory diseases that also feature constriction such as cramping of the gut and inflammatory bowel disease.

The paper is in collaboration with the University of Leicester and funded by Wellcome, Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the American Asthma Foundation.

ENDS

NOTES TO EDITORS:

Figures from Asthma + Lung UK website: https://www.asthmaandlung.org.uk/conditions/asthma/what-asthma

From Asthma + Lung UK’s Asthma and Behavioural Insights resource: Asthma Behavioural Insights | Asthma + Lung UK (asthmaandlung.org.uk)

Fallas A, et al, Creating behavioural personas to drive better design in health technology for asthma self-management. Thorax 2021;76

Professor Rosenblatt’s lab moved on secondment to the Francis Crick Institute in February 2024, through the Crick’s university attachment scheme, which allows researchers from UCL, Imperial College London, and King’s College London to set up a research group at the Crick.

END

Discovery of how limiting damage from an asthma attack could stop disease

2024-04-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Less extensive breast cancer surgery results in fewer swollen arms

2024-04-04

It is possible to leave most of the lymph nodes in the armpit, even if one or two of them have metastases larger than two millimetres? This is shown in a trial enrolling women from five countries, led by researchers at Karolinska Institutet and published in the New England Journal of Medicine. The results open up for gentler surgery for patients with breast cancer.

Breast cancer can spread to the lymph nodes in the armpit. However, tumours found only in the breast and armpit lymph nodes are considered a localized disease, with the goal of curing the patient.

A challenging question for breast cancer surgeons revolves around what should ...

Body mapping links our responses to music with their degree of uncertainty and surprise

2024-04-04

Music holds an important place in human culture, and we’ve all felt the swell of emotion that music can inspire unlike almost anything else. But what is it exactly about music that can bring on such intense sensations in our minds and bodies? A new study reported in the journal iScience on April 4 has insight from studies that systematically examine the way perception of unique musical chords elicits specific bodily sensations and emotions.

“This study reveals the intricate interplay between musical uncertainty, prediction ...

Shaking tiny clusters of brain cells, scientists reveal an overlooked protein’s role in traumatic brain injury

2024-04-04

Clinicians often find limited success in treating patients with traumatic brain injury, a condition long linked to contact sports and military services. A new study, published April 4 in the journal Cell Stem Cell, may offer new clues to better solutions. Scientists found a protein, TDP-43, that appears to drive nerve damage right after injury. Moreover, blocking a certain cell surface protein can correct faulty TDP-43 and curb nerve death in mouse and human cells.

“There’s really nothing out there that can prevent the injury ...

Mistreatment in childbirth is common in the US especially among the disadvantaged

2024-04-04

Lack of respectful maternity care in the U.S. culminating in mistreatment in childbirth is a regular occurrence, according to a new study at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Yet until now experiences of this mistreatment had not been widely documented in the United States. The findings are published in JAMA Network Open.

To estimate the prevalence of mistreatment by care providers in childbirth, the researchers collected survey data from a representative sample of people who had a live birth in 2020 ...

New findings shed light on the expanding universe

2024-04-04

An astrophysicist from The University of Texas at Dallas and his colleagues from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) collaboration are at the forefront of an ambitious experiment to study the expansion of the universe and its acceleration.

Dr. Mustapha Ishak-Boushaki, professor of physics in the School of Natural Sciences and Mathematics (NSM) at UT Dallas, is a member of the DESI collaboration, an international group of more than 900 researchers from over 70 institutions around the world engaged in a multiyear experiment to increase understanding of the ...

Feeling the music

2024-04-04

Music which surprises us can be felt in the heart, while music which matches our expectations can bring feelings of calmness and satisfaction, according to a new study. Researchers played eight short tunes made up of just four chords each to over 500 participants. Each tune had a varied mix of surprising and unsurprising, and certain and uncertain chord progressions. When asked to report how the tunes made them feel and where they were affected, participants’ answers showed that fluctuations in predictions about chord sequences were felt in specific parts of the body, notably the heart and abdomen. Researchers also ...

Nerve stimulation for sleep apnea is less effective for people with higher BMIs

2024-04-04

A nerve-stimulation treatment for obstructive sleep apnea that originally was approved only for people with body mass indexes (BMIs) in the healthy range recently was extended to patients with BMIs up to 40, a weight range generally described as severely obese. A healthy BMI ranges from 18.5 to 24.9.

The expanded eligibility criteria for the treatment provide more sleep apnea patients with access to the increasingly popular therapy, known as hypoglossal nerve stimulation. However, new research from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis indicates that the likelihood of successful nerve-stimulation treatment ...

Severity of RSV vs COVID-19 and influenza among hospitalized US adults

2024-04-04

About The Study: Among 7,998 adults hospitalized during the 16 months before the first respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine recommendations, RSV disease was less common but similar in severity compared with COVID-19 or influenza disease among unvaccinated patients and more severe than COVID-19 or influenza disease among vaccinated patients for the most serious outcomes of invasive mechanical ventilation or death.

Authors: Diya Surie, M.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in ...

Functional limitations and exercise intolerance in patients with post-COVID condition

2024-04-04

About The Study: In this randomized crossover clinical trial with 62 participants, non-hospitalized patients with post-COVID condition (PCC) generally tolerated exercise with preserved cardiovascular function but showed lower aerobic capacity and less muscle strength than the control group. They also showed signs of postural orthostatic tachycardia and myopathy. The findings suggest cautious exercise adoption could be recommended to prevent further skeletal muscle deconditioning and health impairment in patients with PCC.

Authors: Andrea Tryfonos, Ph.D., of the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, is the corresponding author.

To ...

Post-COVID not necessarily a barrier to exercise

2024-04-04

People suffering from post-COVID have been discouraged from exercising because early observations suggested it could be harmful. In a study published in JAMA Network Open, researchers from Karolinska Institutet show that post-covid does not mean that exercise must be strictly avoided.

People affected by post-COVID often experience symptoms such as extreme fatigue, shortness of breath, high resting heart rate, and muscle weakness. Symptoms are often exacerbated by exertion.

“The World Health Organization (WHO) and other major bodies have said that people with post-covid ...