(Press-News.org) Pregnancy may carry a cost, reports a new study from the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. The research, carried out among 1735 young people in the Philippines, shows that women who reported having been pregnant looked biologically older than women who had never been pregnant, and women who had been pregnant more often looked biologically older than those who reported fewer pregnancies. Notably, the number of pregnancies fathered was not associated with biological aging among same-aged cohort men, which implies that it is something about pregnancy or breastfeeding specifically that accelerates biological aging. The findings are published in The Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences.

This study builds on epidemiological findings that high fertility can have negative side effects on women’s health and longevity. What was unknown, however, was whether the costs of reproduction were present earlier in life, before disease and age-related decline start to become apparent. Until now, one of the challenges has been quantifying biological aging among the young. This challenge was overcome by using a collection of new tools that use DNA methylation (DNAm) to study different facets of cellular aging, health, and mortality risk. These tools, called ‘epigenetic clocks’ allow researchers to study aging earlier in life, filling a key gap in the study of biological aging.

“Epigenetic clocks have revolutionized how we study biological aging across the lifecourse and open up new opportunities to study how and when long-term health costs of reproduction and other life events take hold”, said Calen Ryan PhD, lead author of the study and associate research scientist in the Columbia Aging Center.

“Our findings suggest that pregnancy speeds up biological aging, and that these effects are apparent in young, high-fertility women,” said Ryan. “Our results are also the first to follow the same women through time, linking changes in each woman’s pregnancy number to changes in her biological age.”

The relationship between pregnancy history and biological age persisted even after taking into account various other factors tied to biological aging, such as socioeconomic status, smoking, and genetic variation, but were not present among men from the same sample. This finding, noted Ryan, points to some aspect of bearing children – rather than sociocultural factors associated with early fertility or sexual activity – as a driver of biological aging.

Despite the striking nature of the findings, Ryan encourages readers to remember the context: “Many of the reported pregnancies in our baseline measure occurred during late adolescence, when women are still growing. We expect this kind of pregnancy to be particularly challenging for a growing mother, especially if her access to healthcare, resources, or other forms of support is limited.”

Ryan also acknowledged that there is more work to do, “We still have a lot to learn about the role of pregnancy and other aspects of reproduction in the aging process. We also do not know the extent to which accelerated epigenetic aging in these particular individuals will manifest as poor health or mortality decades later in life.”

Ryan said that our current understanding of epigenetic clocks and how they predict health and mortality comes largely from North America and Europe, but that the aging process can take slightly different forms in the Philippines and other places around the world.

“Ultimately I think our findings highlight the potential long-term impacts of pregnancy on women’s health, and the importance of taking care of new parents, especially young mothers.”

Co-authors are Christopher Kuzawa, Northwestern University, Nanette R. Lee and Delia B. Carba, USC-Office of Population Studies Foundation; Julie L. MacIsaac, David S. Lin, and Parmida Atashzay, University of British Columbia; Daniel Belsky Columbia Public Health and Columbia Aging Center; Michael S. Kobor, University of British Columbia, Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, Centre for Molecular Medicine and Therapeutics.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01AG061006; National Science Foundation BCS 1751912; University of British Columbia UBC 60055724.

The Robert N. Butler Columbia Aging Center

Bringing together the campus-wide resources of a top-tier research university, the Robert N. Butler Columbia Aging Center approach to aging science is an innovative, multidisciplinary one with an eye to practical and policy implications. Its mission is to add to the knowledge base needed to better understand the aging process and the societal implications of our increased potential for living longer lives. For more information about this center which is based at the Columbia Mailman School of Public Health, please visit: aging.columbia.edu.

Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

Founded in 1922, the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health pursues an agenda of research, education, and service to address the critical and complex public health issues affecting New Yorkers, the nation and the world. The Columbia Mailman School is the fourth largest recipient of NIH grants among schools of public health. Its nearly 300 multi-disciplinary faculty members work in more than 100 countries around the world, addressing such issues as preventing infectious and chronic diseases, environmental health, maternal and child health, health policy, climate change and health, and public health preparedness. It is a leader in public health education with more than 1,300 graduate students from 55 nations pursuing a variety of master’s and doctoral degree programs. The Columbia Mailman School is also home to numerous world-renowned research centers, including ICAP and the Center for Infection and Immunity. For more information, please visit www.mailman.columbia.edu.

END

University of Michigan researchers have discovered that a worm commonly used in the study of biology uses a set of proteins unlike those seen in other studied organisms to protect the ends of its DNA.

In mammals, shelterin is a complex of proteins that "shelters" the ends of our chromosomes from unraveling or fusing together. Keeping chromosomes from fusing together is an important job: chromosomes carry our body's DNA. If chromosome ends fuse, or if they fuse with other chromosomes, ...

One of the most abundant and deadliest organisms on earth is a virus called a bacteriophage (phage). These predators have lethal precision against their targets – not humans, but bacteria. Different phages have evolved to target different bacteria and play a critical role in microbial ecology. Recently, ADA Forsyth scientists exploring the complex interactions of microbes in the oral microbiome discovered a third player influencing the phage-bacterial arms race – ultrasmall bacterial parasites, called Saccharibacteria or TM7.

In the study, which appeared in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences ...

Some deeper areas of the Great Barrier Reef are insulated from harmful heatwaves – but that protection will be lost if global warming continues, according to new research.

High surface temperatures have caused mass “bleaching” of the Great Barrier Reef in five of the last eight years, with the latest happening now.

Climate change projections for coral reefs are usually based on sea surface temperatures, but this overlooks the fact that deeper water does not necessarily experience the same warming as that at the surface.

The new study – ...

Researchers at the University of California San Diego School of Global Policy and Strategy have developed a new method to predict the financial impacts climate change will have on agriculture, which can help support food security and financial stability for countries increasingly prone to climate catastrophes.

The study, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, uses climate and agricultural data from Brazil. It finds that climate change has a cascading effect on farming, leading to increased loan defaults for ...

MSU has a satellite uplink/LTN TV studio and Comrex line for radio interviews upon request.

EAST LANSING, Mich. – The prevalence of early knee osteoarthritis (OA) symptoms faced by patients after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction is staggering — but not much is being done to address it according to new research published by scholars from Michigan State University’s Department of Kinesiology.

The study – published by the Journal of Athletic ...

Conspiracy theorists get a bad rap in popular culture, yet research has shown that most Americans believe conspiracy theories of some sort. Why then, if most of us believe conspiracies, do we generally think of conspiracy theorists as loony?

New research from the University of Illinois Chicago found that it’s because people are quite bad at identifying what is or isn’t a conspiracy theory when it’s something they believe. The finding held true whether people self-identified as being liberal ...

By Beth Miller

Pulse oximeters send light through a clip attached to a finger to measure oxygen levels in the blood noninvasively. Although the technology has been used for decades — and was heavily used during the COVID-19 pandemic — there is increasing evidence that it has a major flaw: it may provide inaccurate readings in individuals with more melanin pigment in their skin. The problem is so pervasive that the U.S. Food & Drug Administration recently met to find new ways to better evaluate the accuracy and performance of the devices in patients with more pigmented skin.

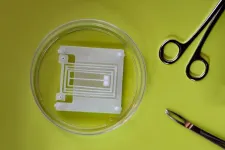

Christine O’Brien, assistant professor of biomedical ...

Children’s literature became a distinct category during the Progressive Era in the United States, largely through the work of professional “book women” like children’s librarians, publishers, and teachers. In a chapter in a new book, researchers examine one of the first attempts to formalize a selection of existing literature into a canon of children’s books, the 1882 pamphlet Books for the Young by Caroline M. Hewins. They also analyze the books selected by Hewins, with a focus on books designated for boys only and for girls only.

The ...

Another decline in net farm income is projected for the Show-Me State, according to the Spring 2024 Missouri Farm Income Outlook released by the University of Missouri’s Rural and Farm Finance Policy Analysis Center (RaFF).

The report offers a state-level glimpse at projected farm financial indicators, including farm receipts, production expenses and other components that affect net farm income. Projections from the report suggest that declining market receipts and lower crop prices play a role in the estimated $0.8 billion decrease in net farm income for 2024.

“Although decreased production expenses offer some relief, reduced livestock inventories ...

Our muscles are nature’s perfect actuators — devices that turn energy into motion. For their size, muscle fibers are more powerful and precise than most synthetic actuators. They can even heal from damage and grow stronger with exercise.

For these reasons, engineers are exploring ways to power robots with natural muscles. They’ve demonstrated a handful of “biohybrid” robots that use muscle-based actuators to power artificial skeletons that walk, swim, pump, and grip. But for every bot, there’s a very different build, and no general blueprint for how to get the most out of muscles ...