(Press-News.org) Sport junkie or couch potato? Always on time or often late? The animal kingdom, too, is home to a range of personalities, each with its own lifestyle. In a study just released in the journal PLOS Biology, a team led by Sören Häfker and Kristin Tessmar-Raible from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) and the University of Vienna report on a surprising discovery: even simple marine polychaete worms shape their day-to-day lives on the basis of highly individual rhythms. This diversity is of interest not just for the future of species and populations in a changing environment, but also for medicine.

At first glance, the star of the new study may not seem particularly impressive: only a few centimetres long, Platynereis dumerilii is a species of polychaete worm that can be found in temperate to tropical coastal waters around the globe; if your goal is to find outstanding animal personalities, surely there are better suited candidates. But that wasn’t the primary goal of the study, which experts from the AWI, the Max Perutz Labs in Vienna, the Universities of Vienna and Oldenburg, and the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium contributed to. First and foremost, the researchers were interested in the internal clocks that dictate countless organisms’ daily rhythms.

“Biological timing is important at a number of levels,” explains Kristin Tessmar-Raible, a biologist at the AWI. “The ecological ties between species depend just as much on it as they do on biochemical processes at the cellular level.” But how do organisms’ internal clocks react when human beings warm the climate or use artificial light to turn night into day? “When it comes to marine organisms, we still know very little,” says Sören Häfker, the study’s main author. In this regard, rhythms are especially important in their lives: temperature, available light and food, and various other factors change throughout the day, and the organisms have to respond accordingly. They adapt their behaviour, metabolism, and genetic activity to these external rhythms.

However, it remains unclear whether they’ll be equally successful at doing so in the future. And when their internal clocks no longer match their environment, it can become a matter of survival. “As such, we need a much better understanding of how the rhythms of the oceans are changing and what it will mean for individual species and populations,” the biologist stresses – which means there’s a wealth of reasons to take a closer look at the daily behaviour of Platynereis dumerilii. In fact, for chronobiology, which focuses on organisms’ internal clocks, this distant relative of the dew worm has become one of the most important model species.

In past experiments, the team had noticed how the worms had quite disparate daily rhythms. Among human beings, it’s a familiar phenomenon: early birds rarely turn into night owls, and vice versa. But what about in marine polychaete worms? Are their behavioural differences just random variations or do they also have a personal tact? To find out, the group systematically observed the worms’ daily activities when there was a new moon. What they saw: some individuals became active at exactly the same time every night. In turn, others appeared to be arrhythmic “couch potatoes” that were only occasionally active – plus, there were various “shades of grey” between these two extremes. When the same worms were observed again several weeks later, their behaviour remained largely unchanged: once a couch potato, always a couch potato. “We were very surprised to see how reproducible the individual behavioural rhythms were,” says Tessmar-Raible. “This shows us that even worms have tiny, rhythmic personalities, so to speak.”

More individuality = more resiliency

To gain further insights into these behavioural differences, the group systematically compared the genetic activity in the heads of worms prone to particularly rhythmic and arrhythmic behaviour. Surprisingly, they found that the daily internal clock worked perfectly fine in all specimens, even the arrhythmic “couch potatoes,” and that the number of genes with rhythmic activity was nearly as high as in the “punctual” worms. The wide range of strategies they employ could offer the worms an evolutionary edge, as the experts surmise. After all, they live in a coastal environment with highly variable conditions; as such, lifestyle A might be the best choice for a given spot, while not far away, lifestyle B might be a better fit. In addition, this form of individuality could make them more resilient to major anthropogenic changes – in a transforming world, this diversity increases the chances of at least some worms being able to cope with their new circumstances.

But the study doesn’t just offer new insights into marine rhythms; it also underscores the fact that the processes at work within a given organism aren’t necessarily reflected in its behaviour: even among the couch potato worms, the genetic activity follows a daily rhythm, even if it’s not externally recognisable. And that’s likely true not just for worms, but for human beings as well. “That’s why such findings are also exciting for fields like chronomedicine,” says Tessmar-Raible.

In recent years, there have been intensified and successful efforts to bear patients’ individual daily rhythms in mind in the context of treating them. But, just as with the worms observed, they consist of various components, ranging from behaviour to genetic activity, which can react differently to medications and the timing of when they are administered. Accordingly, especially when it comes to human beings, it is important for chronomedical analyses to consider several different levels – if even worms can be so individualistic, our species is likely no exception.

END

No two worms are alike

New study confirms that even the simplest marine organisms tend to be individualistic

2024-04-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

AGA announces new partnership with Target RWE to gather real world data on eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE)

2024-04-15

Bethesda, MD (April 15, 2024) - The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and Target RWE have partnered to significantly expand real-world data available for serious, and often chronic, gastroenterological diseases. This partnership will also allow Target RWE to incorporate AGA’s eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) severity index tool, I-SEE, into the TARGET-GASTRO registry.

AGA led the international team of more than 30 multidisciplinary experts that developed the Index of Severity for EoE (I-SEE) in 2022. I-SEE is the first-ever severity index for eosinophilic esophagitis, which provides a simple system for physicians to assess and track ...

How trauma gets 'under the skin'

2024-04-15

A University of Michigan study has shown that traumatic experiences during childhood may get "under the skin" later in life, impairing the muscle function of people as they age.

The study examined the function of skeletal muscle of older adults paired with surveys of adverse events they had experienced in childhood. It found that people who experienced greater childhood adversity, reporting one or more adverse events, had poorer muscle metabolism later in life. The research, led by University of Michigan Institute for Social Research scientist Kate Duchowny, is published in Science Advances.

Duchowny and her co-authors used ...

Researchers resolve old mystery of how phages disarm pathogenic bacteria

2024-04-15

MEDIA INQUIRES

WRITTEN BY

Laura Muntean

Ashley Vargo

laura.muntean@ag.tamu.edu

ashley.vargo@ag.tamu.edu

601-248-1891

Depiction ...

Green-to-red transformation of Euglena gracilis using bonito stock and intense red light

2024-04-15

Over the past few years, people have generally become more conscious about the food they consume. Thanks to easier access to information as well as public health campaigns and media coverage, people are more aware of how nutrition ties in with both health benefits and chronic diseases. As a result, there is an ongoing cultural shift in most countries, with people prioritizing eating healthily. In turn, the demand for healthier food options and nutritional supplements is steadily growing.

In line with these changes, Assistant Professor Kyohei ...

New study sheds light on the mechanisms underlying the development of malignant pediatric brain tumors

2024-04-15

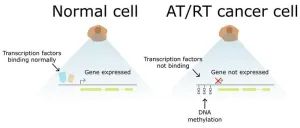

A new study conducted by researchers at Tampere University and Tampere University Hospital revealed how aberrant epigenetic regulation contributes to the development of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid (AT/RT) tumours, which are aggressive brain tumours that mainly affect young children. There is an urgent need for more research in this area as current treatment options are ineffective against these highly malignant tumours.

Most tumours take a long time to develop as harmful mutations gradually accumulate in cells’ DNA over time. AT/RT tumours are a rare exception, ...

Evolution's recipe book: How ‘copy paste’ errors cooked up the animal kingdom

2024-04-15

700 million years ago, a remarkable creature emerged for the first time. Though it may not have been much to look at by today’s standards, the animal had a front and a back, a top and a bottom. This was a groundbreaking adaptation at the time, and one which laid down the basic body plan which most complex animals, including humans, would eventually inherit.

The inconspicuous animal resided in the ancient seas of Earth, likely crawling along the seafloor. This was the last common ancestor of bilaterians, ...

Switch to green wastewater infrastructure could reduce emissions and provide huge savings according to new research

2024-04-15

Embargo: This journal article is under embargo until April 15 at 10 a.m. BST/London (5 a.m. EDT/3 a.m. MDT). Media may conduct interviews around the findings in advance of that date, but the information may not be published, broadcast, or posted online until after the release window. Journalists are permitted to show papers to independent specialists under embargo conditions, solely for the purpose of commenting on the work described

University researchers have shown that a transition to green wastewater-treatment approaches in the U.S. that leverages the potential of carbon-financing could save a staggering $15.6 billion and just under 30 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions ...

Specific nasal cells protect against COVID-19 in children

2024-04-15

Important differences in how the nasal cells of young and elderly people respond to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, could explain why children typically experience milder COVID-19 symptoms, finds a new study led by researchers at UCL and the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

The study, published in Nature Microbiology, focused on the early effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the cells first targeted by the viruses, the human nasal epithelial cells (NECs).

These cells were donated from healthy participants from Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), University College London Hospital (UCLH) and the Royal ...

Tropical forests can't recover naturally without fruit eating birds

2024-04-15

New research from the Crowther Lab at ETH Zurich illustrates a critical barrier to natural regeneration of tropical forests. Their models – from ground-based data gathered in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil - show that when wild tropical birds move freely across forest landscapes, they can increase the carbon storage of regenerating tropical forests by up to 38 percent.

Birds seed carbon potential

Fruit eating birds such as the Red-Legged Honeycreeper, Palm Tanager, or the Rufous-Bellied Thrush play a vital role in forest ecosystems by consuming, excreting, and ...

Newly sequenced genome reveals coffee’s prehistoric origin story — and its future under climate change

2024-04-15

BUFFALO, N.Y. — The key to growing coffee plants that can better resist climate change in the decades to come may lie in the ancient past.

Researchers co-led by the University at Buffalo have created what they say is the highest quality reference genome to date of the world’s most popular coffee species, Arabica, unearthing secrets about its lineage that span millennia and continents.

Their findings, published today in Nature Genetics, suggest that Coffea arabica developed more than 600,000 years ago in the forests of Ethiopia ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

A clinical reveals that aniridia causes a progressive loss of corneal sensitivity

Fossil amber reveals the secret lives of Cretaceous ants

Predicting extreme rainfall through novel spatial modeling

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

[Press-News.org] No two worms are alikeNew study confirms that even the simplest marine organisms tend to be individualistic