(Press-News.org) The energy density of supercapacitors – battery-like devices that can charge in seconds or a few minutes – can be improved by increasing the ‘messiness’ of their internal structure.

Researchers led by the University of Cambridge used experimental and computer modelling techniques to study the porous carbon electrodes used in supercapacitors. They found that electrodes with a more disordered chemical structure stored far more energy than electrodes with a highly ordered structure.

Supercapacitors are a key technology for the energy transition and could be useful for certain forms of public transport, as well as for managing intermittent solar and wind energy generation, but their adoption has been limited by poor energy density.

The researchers say their results, reported in the journal Science, represent a breakthrough in the field and could reinvigorate the development of this important net-zero technology.

Like batteries, supercapacitors store energy, but supercapacitors can charge in seconds or a few minutes, while batteries take much longer. Supercapacitors are far more durable than batteries, and can last for millions of charge cycles. However, the low energy density of supercapacitors makes them unsuitable for delivering long-term energy storage or continuous power.

“Supercapacitors are a complementary technology to batteries, rather than a replacement,” said Dr Alex Forse from Cambridge’s Yusuf Hamied Department of Chemistry, who led the research. “Their durability and extremely fast charging capabilities make them useful for a wide range of applications.”

A bus, train or metro powered by supercapacitors, for example, could fully charge in the time it takes to let passengers off and on, providing it with enough power to reach the next stop. This would eliminate the need to install any charging infrastructure along the line. However, before supercapacitors are put into widespread use, their energy storage capacity needs to be improved.

While a battery uses chemical reactions to store and release charge, a supercapacitor relies on the movement of charged molecules between porous carbon electrodes, which have a highly disordered structure. “Think of a sheet of graphene, which has a highly ordered chemical structure,” said Forse. “If you scrunch up that sheet of graphene into a ball, you have a disordered mess, which is sort of like the electrode in a supercapacitor.”

Because of the inherent messiness of the electrodes, it’s been difficult for scientists to study them and determine which parameters are the most important when attempting to improve performance. This lack of clear consensus has led to the field getting a bit stuck.

Many scientists have thought that the size of the tiny holes, or nanopores, in the carbon electrodes was the key to improved energy capacity. However, the Cambridge team analysed a series of commercially available nanoporous carbon electrodes and found there was no link between pore size and storage capacity.

Forse and his colleagues took a new approach and used nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy – a sort of ‘MRI’ for batteries – to study the electrode materials. They found that the messiness of the materials – long thought to be a hindrance – was in fact the key to their success.

“Using NMR spectroscopy, we found that energy storage capacity correlates with how disordered the materials are – the more disordered materials are able to store more energy,” said first author Xinyu Liu, a PhD candidate co-supervised by Forse and Professor Dame Clare Grey. “Messiness is something that’s hard to measure – it’s only possible thanks to new NMR and simulation techniques, which is why messiness is a characteristic that’s been overlooked in this field.”

When analysing the electrode materials with NMR spectroscopy, a spectrum with different peaks and valleys is produced. The position of the peak indicates how ordered or disordered the carbon is. “It wasn’t our plan to look for this, it was a big surprise,” said Forse. “When we plotted the position of the peak against energy capacity, a striking correlation came through – the most disordered materials had a capacity almost double that of the most ordered materials.”

So why is mess good? Forse says that’s the next thing the team is working on. More disordered carbons store ions more efficiently in their nanopores, and the team are hoping to use these results to design better supercapacitors. The messiness of the materials is determined at the point they are synthesised.

“We want to look at new ways of making these materials, to see how far messiness can take you in terms of improving energy storage,” said Forse. “It could be a turning point for a field that’s been stuck for a little while. Clare and I started working on this topic over a decade ago, and it’s exciting to see a lot of our previous fundamental work now having a clear application.”

The research was supported in part by the Cambridge Trusts, the European Research Council, and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).

END

Mess is best: disordered structure of battery-like devices improves performance

2024-04-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

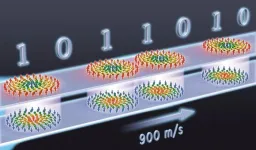

Skyrmions move at record speeds: a step towards the computing of the future

2024-04-18

An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be moved by electrical currents, attaining record speeds up to 900 m/s.

Anticipated as future bits in computer memory, these nanobubbles offer enhanced avenues for information processing in electronic devices. Their tiny size3 provides great computing and information storage capacity, as well as low energy consumption.

Until now, these nanobubbles moved no faster than 100 m/s, which is too slow for computing applications. ...

A third of China’s urban population at risk of city sinking, new satellite data shows

2024-04-18

Land subsidence is overlooked as a hazard in cities, according to scientists from the University of East Anglia (UEA) and Virginia Tech.

Writing in the journal Science, Prof Robert Nicholls of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at UEA and Prof Manoochehr Shirzaei of Virginia Tech and United Nations University for Water, Environment and Health, Ontario, highlight the importance of a new research paper analysing satellite data that accurately and consistently maps land movement across China.

While they say in their comment article that consistently measuring subsidence is a great achievement, they argue it is only the start of finding solutions. Predicting ...

International experts issue renewed call for Global Plastics Treaty to be grounded in robust science

2024-04-18

With negotiations around the Global Plastics Treaty set to resume next week, an international group of scientists has renewed calls for the ambitions and commitments of the Treaty to be driven by robust scientific evidence that is free from conflicts of interest.

Government officials from across the world, and around 4,000 observers representing different aspects in society will gather in Ottawa, Canada, from April 23 to 29 for the fourth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-4).

It will be the fourth of an expected five sessions convened to negotiate an international and legally binding global treaty after the mandate ...

Novel material supercharges innovation in electrostatic energy storage

2024-04-18

By Shawn Ballard

Electrostatic capacitors play a crucial role in modern electronics. They enable ultrafast charging and discharging, providing energy storage and power for devices ranging from smartphones, laptops and routers to medical devices, automotive electronics and industrial equipment. However, the ferroelectric materials used in capacitors have significant energy loss due to their material properties, making it difficult to provide high energy storage capability.

Sang-Hoon Bae, assistant professor of mechanical engineering and materials science in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in ...

A common pathway in the brain that enables addictive drugs to hijack natural reward processing has been identified by Mount Sinai

2024-04-18

Mount Sinai researchers, in collaboration with scientists at The Rockefeller University, have uncovered a mechanism in the brain that allows cocaine and morphine to take over natural reward processing systems. Published online in Science on April 18, these findings shed new light on the neural underpinnings of drug addiction and could offer new mechanistic insights to inform basic research, clinical practice, and potential therapeutic solutions.

“While this field has been explored for decades, our study is ...

China’s sinking cities indicate global-scale problem, Virginia Tech researcher says

2024-04-18

Sinking land is overlooked as a hazard in urban areas globally, according to scientists from Virginia Tech and the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom.

In an invited perspective article for the journal Science, Virginia Tech’s Manoochehr Shirzaei collaborated with Robert Nicholls of the University of East Anglia to highlight the importance of recent research analyzing how and why land is sinking — including a study published in the same issue that focused on sinking Chinese cities.

Results from the accompanying research study showed that ...

Study finds potential new treatment path for lasting Lyme disease symptoms

2024-04-18

Tulane University researchers have identified a promising new approach to treating persistent neurological symptoms associated with Lyme disease, offering hope to patients who suffer from long-term effects of the bacterial infection, even after antibiotic treatment. Their results were published in Frontiers in Immunology.

Lyme disease, caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi and transmitted through tick bites, can lead to a range of symptoms, including those affecting the central ...

Metabolic health before vaccination determines effectiveness of anti-flu response

2024-04-18

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – April 18, 2024) Metabolic health (normal blood pressure, blood sugar and cholesterol levels, among other factors) influences the effectiveness of influenza vaccinations. Vaccination is known to be less effective in people with obesity compared to those with a healthier body mass index (BMI), but St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital scientists have found it is not obesity itself, but instead metabolic dysfunction, which makes the difference. In a study published today in Nature Microbiology, the researchers found switching obese mice to a healthy diet before flu vaccination, but not after, completely protected ...

Department of Energy announces $16 million for traineeships in accelerator science & engineering

2024-04-18

WASHINGTON, D.C. - Today, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) announced $16 million in funding for four projects providing classroom training and research opportunities to train the next generation of accelerator scientists and engineers needed to deliver scientific discoveries.

U.S. global competitiveness in discovery science relies on increasingly complex charged particle accelerator systems that require world-leading expertise to develop and operate. These programs will train the next generation of scientists and engineers, providing the expertise needed ...

MRE 2024 Publication of Enduring Significance Awards

2024-04-18

Marine Resource Economics (MRE) is pleased to announce the 2024 winners of the journal’s Publication of Enduring Significance Award: Kenneth Ruddle, Edvard Hviding, and Robert E. Johannes for their 1992 article, “Marine Resources Management in the Context of Customary Tenure,” and Frank Asche for his 2008 contribution entitled “Farming the Sea.”

In “Marine Resources Management in the Context of Customary Tenure,” Ruddle, Hviding, and Johannes use a case study-based analysis to show how and why customary marine sea ...