(Press-News.org) Contrary to previous assumptions, nerve cells in the human neocortex are wired differently than in mice. Those are the findings of a new study conducted by Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and published in the journal Science.* The study found that human neurons communicate in one direction, while in mice, signals tend to flow in loops. This increases the efficiency and capacity of the human brain to process information. These discoveries could further the development of artificial neural networks.

The neocortex, a critical structure for human intelligence, is less than five millimeters thick. There, in the outermost layer of the brain, 20 billion neurons process countless sensory perceptions, plan actions, and form the basis of our consciousness. How do these neurons process all this complex information? That largely depends on how they are “wired” to each other.

More complex neocortex – different information processing

“Our previous understanding of neural architecture in the neocortex is based primarily on findings from animal models such as mice,” explains Prof. Jörg Geiger, Director of the Institute for Neurophysiology at Charité. In those models, the neighboring neurons frequently communicate with each other as if they are in dialogue. One neuron signals another, and then that one sends a signal back. That means the information often flows in recurrent loops.”

The human neocortex is much thicker and more complex than that of a mouse. Nonetheless, researchers had previously assumed – in part due to lack of data – that it follows the same basic principles of connectivity. A team of Charité researchers led by Geiger has now used exceptionally rare tissue samples and state-of-the-art technology to demonstrate that this is not the case.

A clever method of listening in on neuronal communication

For the study, the researchers examined brain tissue from 23 people who had undergone neurosurgery at Charité to treat drug-resistant epilepsy. During surgery, it was medically necessary to remove brain tissue in order to gain access to the diseased structures beneath it. The patients had consented to the use of this access tissue for research purposes.

To be able to observe the flows of signals between neighboring neurons in the outermost layer of the human neocortex, the team developed an improved version of what is known as the “multipatch” technique. This allowed the researchers to listen in on the communications taking place between as many as ten neurons at once (for details, see “About the method”). As a result, they were able to take the necessary number of measurements to map the network in the short time before the cells ceased their activity outside the body. In all, they analyzed the communication channels among nearly 1,170 neurons with about 7,200 possible connections.

Feed-forward instead of in cycles

They found that only a small fraction of the neurons engaged in reciprocal dialogue with each other. “In humans, the information tends to flow in one direction instead. It seldom returns to the starting point either directly or via cycles,” explains Dr. Yangfan Peng, first author of the publication. He worked on the study at the Institute for Neurophysiology and is now based at the Department of Neurology and the Neuroscience Research Center at Charité. The team used a computer simulation that they devised according to the same principles underlying the human network architecture to demonstrate that this forward-directed signal flow has benefits in terms of processing data.

The researchers gave the artificial neural network a typical machine learning task: recognizing the correct numbers from audio recordings of spoken digits. The network model that mimicked the human structures achieved more correct responses to this speech recognition task than the one modeled on mice. It was also more efficient, with the same performance requiring the equivalent of 380 neurons in the mouse model, but only 150 in the human one.

An economic role model for AI?

“The directed network architecture we see in humans is more powerful and conserves resources because more independent neurons can handle different tasks simultaneously,” Peng explains. “This means that the local network can store more information. It isn’t clear yet whether our findings within the outermost layer of the temporal cortex extend to other cortical regions, or how well they might explain the unique cognitive abilities of humans.”

In the past, AI developers have looked to biological models for inspiration in designing artificial neural networks, but have also optimized their algorithms independently of the biological models. “Many artificial neural networks already use some form of this forward-directed connectivity because it delivers better results for some tasks,” Geiger says. “It’s fascinating to see that the human brain also shows similar network principles. These insights into cost-efficient information processing in the human neocortex could provide further inspiration for refining AI networks.”

*Peng Y. et al. Directed and acyclic synaptic connectivity in the human layer 2-3 cortical microcircuit. Science 2024 Apr 18. doi: 10.1126/science.adg8828

About the study

The work was done in close cooperation between the basic research and clinical departments of Charité. Under the leadership of the Institute of Neurophysiology, the following were involved: the Department of Neurosurgery, the Department of Neurology with Experimental Neurology, the Institute of Integrative Neuroanatomy, the Department of Neuropathology, the Neuroscience Research Center, and the NeuroCure Cluster of Excellence, with support from the University Clinic for Neurosurgery at Evangelisches Klinikum Bethel and the Institute of Neuroinformatics at ETH Zurich.

About the method

When surgery is performed to treat drug-resistant, or refractory, epilepsy, it is often medically necessary to remove brain tissue. The explicit consent of patients was required in order to examine this valuable tissue for the study that has just been published. The research group is profoundly grateful to the patients for their consent. The authors used what is known as the “patch-clamp” method to analyze synaptic communication between neurons. In this technique, an ultra-thin glass pipette is attached to a single neuron under a microscope to measure or stimulate the cell’s electrical activity. The study utilized an advanced form of this technique in which multiple of these micropipettes simultaneously record the activity and connectivity of up to ten neurons (the “multipatch” method). To be able to position the pipettes precisely, the device is equipped with robot arms that enable movements in the nanometer range. The measurement process is highly challenging and labor-intensive. Using two devices in parallel allowed the team to study several hundred connections between the nerve cells for each tissue sample. The brain tissue can be preserved for up to two days outside the body in an artificial nutrient solution before activity ceases.

END

When thoughts flow in one direction

Charité study in Science decodes wiring of the human neocortex

2024-04-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists identify airway cells that sense aspirated water and acid reflux

2024-04-18

Scientists Identify Airway Cells That Sense Aspirated Water and Acid Reflux

The new work by UCSF researchers could lead to interventions to prevent pneumonia or treat certain types of chronic cough.

When a mouthful of water goes down the wrong pipe – heading toward a healthy person’s lungs instead of their gut – they start coughing uncontrollably. That’s because their upper airway senses the water and quickly signals the brain. The same coughing reflex is set off in people with acid reflux, when acid from the stomach reaches the throat.

Now, UC San Francisco scientists have identified the rare type of cell responsible ...

China’s major cities show considerable subsidence from human activities

2024-04-18

The land under nearly half of China’s major cities is undergoing moderate to severe subsidence, affecting roughly one-third of the nation’s urban population, according to a systematic national-scale satellite assessment. The findings suggest that within the next century, 22 to 26% of China’s coastal land will have a relative elevation lower than sea level, putting hundreds of millions of people at elevated risk of flooding due to sea-level rise. Over the last several decades, China has experienced one of the most rapid and extensive urban expansions in human history. This massive wave of urbanization may be threatened ...

Drugs of abuse alter neuronal signaling to reprioritize use over innate needs

2024-04-18

Drugs of abuse, like cocaine and opioids, alter neuronal signaling in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), hijacking a key brain reward system involved with the fulfillment of innate needs for survival, according to a new study in mice. The findings provide mechanistic insights into the intensification of drug-seeking behaviors in substance use disorders. Persistent drug use is accompanied by a profound reprioritization of motivations, skewing decision-making behaviors toward a myopic focus on drug use over other innate needs, like eating or drinking water, often ...

Mess is best: disordered structure of battery-like devices improves performance

2024-04-18

The energy density of supercapacitors – battery-like devices that can charge in seconds or a few minutes – can be improved by increasing the ‘messiness’ of their internal structure.

Researchers led by the University of Cambridge used experimental and computer modelling techniques to study the porous carbon electrodes used in supercapacitors. They found that electrodes with a more disordered chemical structure stored far more energy than electrodes with a highly ordered structure.

Supercapacitors are a key technology for the energy transition and could be useful for certain forms of public transport, as well as for ...

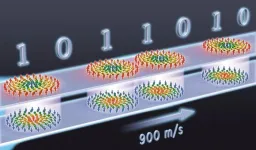

Skyrmions move at record speeds: a step towards the computing of the future

2024-04-18

An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be moved by electrical currents, attaining record speeds up to 900 m/s.

Anticipated as future bits in computer memory, these nanobubbles offer enhanced avenues for information processing in electronic devices. Their tiny size3 provides great computing and information storage capacity, as well as low energy consumption.

Until now, these nanobubbles moved no faster than 100 m/s, which is too slow for computing applications. ...

A third of China’s urban population at risk of city sinking, new satellite data shows

2024-04-18

Land subsidence is overlooked as a hazard in cities, according to scientists from the University of East Anglia (UEA) and Virginia Tech.

Writing in the journal Science, Prof Robert Nicholls of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at UEA and Prof Manoochehr Shirzaei of Virginia Tech and United Nations University for Water, Environment and Health, Ontario, highlight the importance of a new research paper analysing satellite data that accurately and consistently maps land movement across China.

While they say in their comment article that consistently measuring subsidence is a great achievement, they argue it is only the start of finding solutions. Predicting ...

International experts issue renewed call for Global Plastics Treaty to be grounded in robust science

2024-04-18

With negotiations around the Global Plastics Treaty set to resume next week, an international group of scientists has renewed calls for the ambitions and commitments of the Treaty to be driven by robust scientific evidence that is free from conflicts of interest.

Government officials from across the world, and around 4,000 observers representing different aspects in society will gather in Ottawa, Canada, from April 23 to 29 for the fourth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-4).

It will be the fourth of an expected five sessions convened to negotiate an international and legally binding global treaty after the mandate ...

Novel material supercharges innovation in electrostatic energy storage

2024-04-18

By Shawn Ballard

Electrostatic capacitors play a crucial role in modern electronics. They enable ultrafast charging and discharging, providing energy storage and power for devices ranging from smartphones, laptops and routers to medical devices, automotive electronics and industrial equipment. However, the ferroelectric materials used in capacitors have significant energy loss due to their material properties, making it difficult to provide high energy storage capability.

Sang-Hoon Bae, assistant professor of mechanical engineering and materials science in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in ...

A common pathway in the brain that enables addictive drugs to hijack natural reward processing has been identified by Mount Sinai

2024-04-18

Mount Sinai researchers, in collaboration with scientists at The Rockefeller University, have uncovered a mechanism in the brain that allows cocaine and morphine to take over natural reward processing systems. Published online in Science on April 18, these findings shed new light on the neural underpinnings of drug addiction and could offer new mechanistic insights to inform basic research, clinical practice, and potential therapeutic solutions.

“While this field has been explored for decades, our study is ...

China’s sinking cities indicate global-scale problem, Virginia Tech researcher says

2024-04-18

Sinking land is overlooked as a hazard in urban areas globally, according to scientists from Virginia Tech and the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom.

In an invited perspective article for the journal Science, Virginia Tech’s Manoochehr Shirzaei collaborated with Robert Nicholls of the University of East Anglia to highlight the importance of recent research analyzing how and why land is sinking — including a study published in the same issue that focused on sinking Chinese cities.

Results from the accompanying research study showed that ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Governing with AI: a new AI implementation blueprint for policymakers

Recent pandemic viruses jumped to humans without prior adaptation, UC San Diego study finds

Exercise triggers memory-related brain 'ripples' in humans, researchers report

Increased risk of bullying in open-plan offices

Frequent scrolling affects perceptions of the work environment

Brain activity reveals how well we mentally size up others

Taiwanese and UK scientists identify FOXJ3 gene linked to drug-resistant focal epilepsy

Pregnancy complications impact women’s stress levels and cardiovascular risk long after delivery

Spring fatigue cannot be empirically proven

Do prostate cancer drugs interact with certain anticoagulants to increase bleeding and clotting risks?

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

Increased connectivity in early Alzheimer’s is lowered by cancer drug in the lab

Study highlights stroke risk linked to recreational drugs, including among young users

Modeling brain aging and resilience over the lifespan reveals new individual factors

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

[Press-News.org] When thoughts flow in one directionCharité study in Science decodes wiring of the human neocortex