(Press-News.org) The gut microbiota is the microbial community that occupies the gastrointestinal tract. It is responsible for producing enzymes, metabolites, and other molecules crucial for host metabolism and in response to the environment.

Consequently, a balanced gut microbiota is important for mammalian health in many ways, such as helping to regulate the immune and endocrine systems. This in turn, impacts the physiology of tissues throughout the body. However, little was known about the impact of the gut microbiota on host reproduction, and whether an altered microbiota in a father could influence the fitness of his offspring.

The Hackett group at EMBL Rome, in collaboration with the Bork and the Zimmermann groups at EMBL Heidelberg, set out to answer this question, with their results now published in the journal Nature. The scientists showed that disrupting the gut microbiota in male mice increases the probability that their offspring are born with low weight, and are more likely to die prematurely. These findings are illustrated in this animation.

What is passed on to the next generation

To study the effects of the gut microbiota on male reproduction and their offspring, the researchers altered the composition of gut microbes in male mice by treating them with common antibiotics that do not enter the bloodstream. This induces a condition called dysbiosis, whereby the microbial ecosystem in the gut becomes unbalanced.

The scientists then analysed changes in the composition of important testicular metabolites. They found that in male mice dysbiosis affects the physiology of the testes, as well as metabolite composition and hormonal signalling. At least part of this effect was mediated by changes in the levels of the key hormone leptin in blood and testes of males with induced dysbiosis. These observations suggest that in mammals, a ‘gut-germline axis’ exists as an important connection between the gut, its microbiota, and the germline.

To understand the relevance of this ‘gut-germline’ axis to traits inherited by offspring, the scientists mated either untreated or dysbiotic males with untreated females. Mouse pups sired by dysbiotic fathers showed significantly lower birth weights and an increased rate of postnatal mortality. Different combinations of antibiotics as well as treatments with dysbiosis-inducing-laxatives (which also disrupt microbiota) affected offspring similarly.

Importantly, this effect is reversible. Once antibiotics are withdrawn, paternal microbiota recover. When mice with recovered microbiota were mated with untreated females, their offspring were born with normal birthweight and developed normally as well.

“We have observed that intergenerational effects disappear once a normal microbiota is restored. That means that any alteration to the gut microbiota able to cause intergenerational effects could be prevented in prospective fathers” said Peer Bork, EMBL Heidelberg Director, who participated in the study. “The next step will be to understand in detail how different environmental factors such as medicinal drugs including antibiotics can affect the paternal germline and, therefore, embryonic development.” Ayele Denboba, first author of the publication and former postdoc in the Hackett Group, now Group Leader at the Max Planck Institute of Immunology and Epigenetics in Freiburg, Germany added "The study originated to understand environmental impacts on fathers by considering the gut microbiota as a nexus of host-environment interactions, thus creating a sufficient-cause model to assess intergenerational health risks in complex ecological systems.”

Paternal impact on pregnancy disease risk

In their work, Hackett and his colleagues also discovered that placental defects, including poor vascularisation and reduced growth, occurred more frequently in pregnancies involving dysbiotic males. The defective placentas exhibited hallmarks of a common pregnancy complication in humans called pre-eclampsia, which leads to impaired offspring growth and is a risk factor for developing a wide range of common diseases later in life.

“Our study demonstrates the existence of a channel of communication between the gut microbiota and the reproductive system in mammals. What’s more, environmental factors that disrupt these signals in prospective fathers increase the risk of adverse health in offspring, through altering placental development” said Jamie Hackett, coordinator of the research project and an EMBL Rome Group Leader. “This implies that in mice, the environment of a father just prior to conception can influence offspring traits independently of genetic inheritance.”

“At the same time, we find the effect is for one generation only, and I should be clear that further studies are needed to investigate how pervasive these effects are and whether they have relevance in humans. There are intrinsic differences to be considered when translating results from mouse models to humans.” Hackett continued: “But given the widespread prevalence of dietary and antibiotic practices in Western culture that are known to disrupt the gut microbiota, it is important to consider paternal intergenerational effects more carefully – and how they may be affecting pregnancy outcomes and population disease risk.”

END

Father’s gut microbes affect the next generation

A study from the Hackett group at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Rome shows that disrupting the gut microbiome of male mice increases the risk of disease in their future offspring.

2024-05-01

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists work out the effects of exercise at the cellular level

2024-05-01

The health benefits of exercise are well known but new research shows that the body’s response to exercise is more complex and far-reaching than previously thought. In a study on rats, a team of scientists from across the United States has found that physical activity causes many cellular and molecular changes in all 19 of the organs they studied in the animals.

Exercise lowers the risk of many diseases, but scientists still don’t fully understand how exercise changes the body on a molecular level. Most studies have focused on a single organ, sex, or time point, and only include one or two data types.

To take a more comprehensive ...

CHOP researchers identify causal genetic variant linked to common childhood obesity

2024-05-01

Philadelphia, May 1, 2024 – Researchers from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) have identified a causal genetic variant strongly associated with childhood obesity. The study provides new insight into the importance of the hypothalamus of the brain and its role in common childhood obesity and the target gene may serve as a druggable target for future therapeutic interventions. The findings were published today in the journal Cell Genomics.

Both environmental and genetic factors play critical roles in the increasing incidence of childhood ...

UVM scientists decode exercise's molecular impact

2024-05-01

BURLNGTON, Vt.—For the past eight years, researchers have been conducting a groundbreaking study supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Common Fund: The Molecular Transducers of Physical Activity Consortium (MoTrPAC). With nearly 2,600 volunteers, the study aims to examine the molecular effects of exercise on healthy adults and children, considering factors like age, race, and gender. The goal is to create comprehensive molecular maps of these changes and uncover why physical activity has significant health benefits.

“This ...

Differences in cardiovascular health at the intersection of race, ethnicity, and sexual identity

2024-05-01

About The Study: This cross-sectional study uses National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data to examine differences in cardiovascular health metrics at the intersection of race, ethnicity, and sexual identity.

Authors: Nicole Rosendale, M.D., of the University of California San Francisco, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.9053)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial ...

Plant-based diets and disease progression in men with prostate cancer

2024-05-01

About The Study: Higher intake of plant foods after prostate cancer diagnosis was associated with lower risk of cancer progression, this study suggests.

Authors: Stacey A. Kenfield, Sc.D., of the University of California, San Francisco, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.9053)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

# # #

Embed this ...

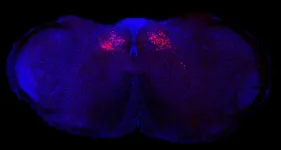

Columbia scientists identify new brain circuit in mice that controls body’s inflammatory reactions

2024-05-01

NEW YORK, NY — The brain can direct the immune system to an unexpected degree, capable of detecting, ramping up and tamping down inflammation, shows a new study in mice from researchers at Columbia's Zuckerman Institute.

"The brain is the center of our thoughts, emotions, memories and feelings," said Hao Jin, PhD, a co-first author of the study published online today in Nature. "Thanks to great advances in circuit tracking and single-cell technology, we now know the brain does far more than that. It is monitoring the function of every system in the body."

Future ...

Nutrient research reveals pathway for treating brain disorders

2024-05-01

A University of Queensland researcher has found molecular doorways that could be used to help deliver drugs into the brain to treat neurological disorders.

Dr Rosemary Cater from UQ’s Institute for Molecular Bioscience led a team which discovered that an essential nutrient called choline is transported into the brain by a protein called FLVCR2.

“Choline is a vitamin-like nutrient that is essential for many important functions in the body, particularly for brain development,” Dr Cater said.

“We need to consume 400-500 mg of choline ...

Nationwide, 6 stroke advocates selected to receive 2024 Stroke Hero Awards

2024-05-01

DALLAS, May 1, 2024 — Each year, approximately 800,000 people in the U.S. have a stroke.[1] Six local stroke heroes from across the country are being recognized by the American Stroke Association, a division of the American Heart Association, for their resiliency and dedication in the fight against stroke.

The American Stroke Association’s annual Stroke Hero Awards honors stroke survivors, health care professionals, advocates and caregivers. During May, American Stroke Month, the Association, ...

Sleep resets brain connections – but only for first few hours

2024-05-01

During sleep, the brain weakens the new connections between neurons that had been forged while awake – but only during the first half of a night’s sleep, according to a new study in fish by UCL scientists.

The researchers say their findings, published in Nature, provide insight into the role of sleep, but still leave an open question around what function the latter half of a night’s sleep serves.

The researchers say the study supports the Synaptic Homeostasis Hypothesis, a key theory on the purpose of sleep which proposes that sleeping acts as a reset for the brain.

Lead author Professor Jason Rihel (UCL Cell & Developmental Biology) said: “When we are awake, ...

Rock solid evidence: Angola geology reveals prehistoric split between South America and Africa

2024-05-01

DALLAS (SMU) – An SMU-led research team has found that ancient rocks and fossils from long-extinct marine reptiles in Angola clearly show a key part of Earth’s past – the splitting of South America and Africa and the subsequent formation of the South Atlantic Ocean.

With their easily visualized “jigsaw-puzzle fit,” it has long been known that the western coast of Africa and the eastern coast of South America once nestled together in the supercontinent Gondwana — which broke off from the larger landmass of Pangea.

The research team says the southern coast of Angola, where they dug up the samples, arguably provides the most complete ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Neighborhood factors may lead to increased COPD-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations

Food insecurity impacts employees’ productivity

Prenatal infection increases risk of heavy drinking later in life

‘The munchies’ are real and could benefit those with no appetite

FAU researchers discover novel bacteria in Florida’s stranded pygmy sperm whales

DEGU debuts with better AI predictions and explanations

‘Giant superatoms’ unlock a new toolbox for quantum computers

Jeonbuk National University researchers explore metal oxide electrodes as a new frontier in electrochemical microplastic detection

Cannabis: What is the profile of adults at low risk of dependence?

Medical and materials innovations of two women engineers recognized by Sony and Nature

Blood test “clocks” predict when Alzheimer’s symptoms will start

Second pregnancy uniquely alters the female brain

Study shows low-field MRI is feasible for breast screening

Nanodevice produces continuous electricity from evaporation

Call me invasive: New evidence confirms the status of the giant Asian mantis in Europe

Scientists discover a key mechanism regulating how oxytocin is released in the mouse brain

Public and patient involvement in research is a balancing act of power

Scientists discover “bacterial constipation,” a new disease caused by gut-drying bacteria

DGIST identifies “magic blueprint” for converting carbon dioxide into resources through atom-level catalyst design

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy may help prevent preeclampsia

Menopausal hormone therapy not linked to increased risk of death

Chronic shortage of family doctors in England, reveals BMJ analysis

Booster jabs reduce the risks of COVID-19 deaths, study finds

Screening increases survival rate for stage IV breast cancer by 60%

ACC announces inaugural fellow for the Thad and Gerry Waites Rural Cardiovascular Research Fellowship

University of Oklahoma researchers develop durable hybrid materials for faster radiation detection

Medicaid disenrollment spikes at age 19, study finds

Turning agricultural waste into advanced materials: Review highlights how torrefaction could power a sustainable carbon future

New study warns emerging pollutants in livestock and aquaculture waste may threaten ecosystems and public health

Integrated rice–aquatic farming systems may hold the key to smarter nitrogen use and lower agricultural emissions

[Press-News.org] Father’s gut microbes affect the next generationA study from the Hackett group at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Rome shows that disrupting the gut microbiome of male mice increases the risk of disease in their future offspring.