(Press-News.org) A new study led by University of Pittsburgh and UPMC Hillman Cancer Center researchers shows that an enzyme called PARP1 is involved in repair of telomeres, the lengths of DNA that protect the tips of chromosomes, and that impairing this process can lead to telomere shortening and genomic instability that can cause cancer.

PARP1’s job is genome surveillance: When it senses breaks or lesions in DNA, it adds a molecule called ADP-ribose to specific proteins, which act as a beacon to recruit other proteins that repair the break. The new findings, published today in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, are the first evidence that PARP1 also acts on telomeric DNA, opening up new avenues for understanding and improving PARP1-inhibiting cancer therapies.

“No one thought that ADP-ribosylation at DNA was possible, but recent findings challenge this dogma,” said Roderick O’Sullivan, Ph.D., associate professor of molecular pharmacology Pitt and investigator at UPMC Hillman. “PARP1 is one of the most important biomedical targets for cancer research, but it was thought that drugs targeting this enzyme only acted at proteins. Now that we know PARP1 also modifies DNA, it changes the game because we can potentially target this aspect of PARP1 biology to improve cancer treatments.”

In normal cells, genomic lesions occur naturally during DNA replication when a cell divides, and PARP1 play an important role in fixing these errors. But while healthy cells have other DNA repair pathways to fall back on, BRCA-deficient cancers — which include many breast and ovarian tumors —rely heavily on PARP1 because they lack BRCA proteins, which control the most effective form of DNA repair called homologous replication.

“When cancer cells can’t make BRCA proteins, they become dependent on repair pathways that PARP1 is involved in,” said O’Sullivan. “So, when you inhibit PARP1 — which is the mechanism of several approved cancer drugs — cancer cells have no repair pathway available, and they die.”

Although scientists discovered PARP1’s role in ADP-ribosylation of proteins about 60 years ago, O’Sullivan and his collaborator, Ivan Ahel, Ph.D., professor in the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology at the University of Oxford and world-renowned expert in PARP1, had a hunch that there was more to learn about this enzyme and its role in cells.

O’Sullivan and his team, led by Anne Wondisford, Ph.D., graduate student in Pitt’s Medical-Scientist Training Program, first compared normal human cells with those deficient in PARP1. Using special antibodies that bind to ADP-ribose and telomere-specific probes, they found that ADP-ribose attaches to telomeric DNA in normal cells but not in PARP1-deficient cells, showing that this enzyme is responsible for ADP-ribosylation of DNA.

Next, they compared normal cells with those deficient in another enzyme called TARG1, which removes ADP-ribose. In absence of TARG1, ADP-ribose accumulated at telomeres, leading to disruption of telomere replication and premature telomere shortening.

To show that these telomere defects were due to modification of telomeric DNA, O’Sullivan and his team took bacterial enzymes that function similarly to PARP1 and put them into human cells.

“We used a guidance system to direct the enzymes to add ADP-ribose only at the telomeres and nowhere else in the genome,” said O’Sullivan. “We found that if we load telomeres with ADP-ribose, their integrity is dramatically impaired, and it can kill the cell within days.”

O’Sullivan hypothesizes that ADP-ribose affects telomere integrity by disrupting a protective structure called shelterin that safeguards telomeres, but more research is needed to confirm this.

“Targeting PARP1 has been a big success story for cancer therapy, but some patients develop resistance to PARP1 inhibitors,” said O’Sullivan. “I’m excited about this study because we’ve discovered something new about PARP1 biology, which generates a whole load of new questions that could help us develop novel approaches to target PARP1 or fine-tune therapies we already have. We’re right at the beginning of something exciting, and there’s a lot more to explore.”

Other authors on the study were Sandra Schamus-Haynes, Ragini Bhargava Ph.D., and Patricia Opresko, Ph.D., all of Pitt and UPMC; Junyeop Lee and Jaewon Min, Ph.D., both of Columbia University; Robert Lu, Ph.D., and Hilda Pickett, Ph.D., both of the University of Sydney; and Marion Schuller, D.Phil., and Josephine Groslambert, both of the University of Oxford.

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01CA207209, R01262316, P30CA047904, T32 GM133332, F30 CA278287, R35ES030396 and K22CA245259), the Wellcome Trust (101794, 210634, 210634 and 223107), the Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance (813369), Cancer Research UK (C35050/A22284), Medical Research Future Fund (2007488) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/R007195/1 and BB/W016613/1).

END

Dogma-challenging telomere findings may offer new insights for cancer treatments

2024-05-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists cooked pancakes, Brussels sprouts, and stir fry to detect an oxidant indoors for the first time

2024-05-07

A feast cooked up by UBC researchers has revealed singlet oxygen indoors for the first time.

Oxi-don’t

Singlet oxygen is an oxidant. These chemical compounds can be beneficial—ozone in the stratosphere is one example—but can also cause stress to our lungs, contributing to the development of cancer, diabetes, and heart disease in the long term.

Cooking foods can release brown carbon, molecules with the potential to create oxidants when they absorb light. In addition, exposure to cooking emissions has been linked to chronic diseases in chefs.

Historically, it was thought there wasn’t enough light indoors to have much ...

Quantum breakthrough: World’s purest silicon brings scientists one step closer to scaling up quantum computers

2024-05-07

More than 100 years ago, scientists at The University of Manchester changed the world when they discovered the nucleus in atoms, marking the birth of nuclear physics.

Fast forward to today, and history repeats itself, this time in quantum computing.

Building on the same pioneering method forged by Ernest Rutherford – "the founder of nuclear physics" – scientists at the University, in collaboration with the University of Melbourne in Australia, have produced an enhanced, ultra-pure form of silicon that allows ...

New super-pure silicon chip opens path to powerful quantum computers

2024-05-07

Researchers at the Universities of Melbourne and Manchester have invented a breakthrough technique for manufacturing highly purified silicon that brings powerful quantum computers a big step closer.

The new technique to engineer ultra-pure silicon makes it the perfect material to make quantum computers at scale and with high accuracy, the researchers say.

Project co-supervisor Professor David Jamieson, from the University of Melbourne, said the innovation – published today in Communication Materials, a Nature journal – uses qubits of phosphorous atoms implanted ...

Millions in costs due to discharge of scrubber water into the Baltic Sea

2024-05-07

Discharge from ships with so-called scrubbers cause great damage to the Baltic Sea. A new study from Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, shows that these emissions caused pollution corresponding to socio-economic costs of more than EUR 680 million between 2014 and 2022. At the same time, the researchers note that the shipping companies' investments in the much-discussed technology, where exhaust gases are "washed" and discharged into the sea, have already been recouped for most of the ships. This means that the industry is now making billions ...

Bio-inspired materials’ potential for efficient mass transfer boosted by a new twist on a century-old theory

2024-05-07

The natural vein structure found within leaves – which has inspired the structural design of porous materials that can maximise mass transfer – could unlock improvements in energy storage, catalysis, and sensing thanks to a new twist on a century-old biophysical law.

An international team of researchers, led by the NanoEngineering Group at the Cambridge Graphene Centre, has developed a new materials theory based on ‘Murray’s Law’, applicable to a wide range of next-generation functional ...

Small pump for kids awaiting heart transplant shows promise in Stanford Medicine-led trial

2024-05-07

A small, implantable cardiac pump that could help children await heart transplants at home, not in the hospital, has performed well in the first stage of human testing.

The pump, a new type of ventricular assist device, or VAD, is surgically attached to the heart to augment its blood-pumping action in individuals with heart failure, allowing time to find a donor heart. The new pump could close an important gap in heart transplant care for children.

In a feasibility trial of seven children who received the new pump to support their failing hearts, six ultimately underwent heart transplants ...

Time flies, but your hands tell: Haut.AI cracks the age code with hand analysis

2024-05-07

Tallinn, Estonia – 7th May 2024, 10 AM CET – Haut.AI, a leader in responsible skincare artificial intelligence (AI) development, today announced a breakthrough research paper demonstrating the effectiveness of using hand images for accurate age prediction. This innovative approach offers a viable alternative to traditional facial photo methods and promotes fairer AI solutions.

The study, titled “Predicting human chronological age via AI analysis of dorsal hand versus facial images: A study in a cohort of Indian females,” shows that AI models trained on hand images achieve comparable accuracy to those using facial images, with an average error of ...

Babraham Institute receives £48M strategic investment from BBSRC for a four-year programme of work to promote lifelong health

2024-05-07

Following a quinquennial review by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), the Babraham Institute will receive £48m for the period 2024-2028 to advance research on the mechanisms that maintain the health of our cells, tissues and organs across the life course.

This work is key in driving BBSRC’s strategic research priorities around an integrated understanding of health, developing and applying transformative technologies and advancing our understanding of the rules of life.

As one of eight UK bioscience ...

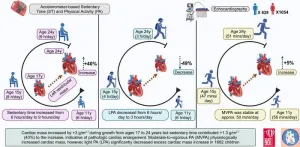

Childhood sedentariness linked to premature heart damage – light physical activity reversed the risk

2024-05-07

An increase in sedentary time from childhood caused progressing heart enlargement, a new study shows. However, light physical activity could reduce the risk. The study was conducted in collaboration between the Universities of Bristol and Exeter, and the University of Eastern Finland, and the results were published in the prestigious European Journal of Preventive Cardiology.

Left ventricular hypetrophy refers to an excessive increase in heart mass and size. In adults, it is known to increase the risk for heart attacks, stroke, and premature death.

In the present study, 1,682 children ...

Parents’ watchful eye may keep young teens from trying alcohol, drugs: Study

2024-05-07

PISCATAWAY, NJ – Teenagers are less likely to drink, smoke or use drugs when their parents keep tabs on their activities--but not necessarily because kids are more likely to be punished for substance use, suggests a new study in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs.

Researchers found that, contrary to common belief, parents’ “monitoring” does not seem to boost the odds of catching their kids using substances. However, when kids simply are aware that their parents are monitoring behavior, they avoid trying alcohol or drugs in the first place.

It is the fear of being caught, rather than actually being punished.

Many studies ...