(Press-News.org) When two animals look the same, eat the same, behave the same way, and live in similar environments, one might expect that they belong to the same species.

However, a tiny zooplankton skimming the ocean surfaces of microscopic food particles challenges this assumption. Researchers from Osaka University, University of Barcelona and the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) have analyzed the genome of Oikopleura dioica from the Seto Inland Sea, the Mediterranean, and the Pacific Ocean around the Okinawa Islands, and in doing so, they have raised numerous questions about speciation and the role of gene location in the genome. Their results have recently been published in Genome Research. “Oikopleura is opening new avenues into genomic research” remarks Dr. Charles Plessy from the Genomics and Regulatory Systems Unit at OIST and co-first author of the paper. “As a model animal, it allows us to study the mechanisms for genome changes in the lab as they happen at a very large scale and speed, which is an enormous opportunity.”

Oikopleura dioica is a tiny zooplankton that inhabits the ocean surface worldwide, and which is used as a model organism in developmental biology. As a chordate, the organism shares key genetic and developmental traits with vertebrates, including the presence of a notochord, which is a chord-like central nerve bundle like a spinal column, but without bones. Moreover, its compact genome, the smallest non-parasitic animal genome reported to date, facilitates large-scale genomic analysis.

You can watch a short documentary about the collection, care, and use of Oikopleura dioica in genomic research at OIST here.

The genomic tower of Babel

The researchers worked on three lineages of Oikopleura dioica sampled from three seas around the world, but though the morphological, behavioral, and ecological characteristics of the lineages are virtually the same, the genomes differ massively.

Think of the genome as a shared language between all members of a single species, stored within the nucleus of every cell and containing the complete set of genetic material to make that species. Like how grammar determines the arrangement of words to convey specific meanings, so too are the basic units of information in the genome – the genes – regulated in relation to one another when they’re transcribed and translated into the fundamental building blocks of life, proteins. Gene regulation involves multiple factors that impact the activation or rate of gene transcription, such as other genes, molecules in the cell, hormones, and many others.

What’s puzzling about the Oikopleura dioica genome is that the languages of the three lineages don’t seem to match, despite them having almost identical physical characteristics. That is, the ‘meaning’ produced by their genes are mostly the same, while the genomic languages are wildly different between them.

The researchers use the term ‘scrambling’ to describe the phenomenon observed in Oikopleura dioica, a term which originates in linguistics to denote a phenomenon whereby sentences are formulated using a variety of different word orders without any change in meaning. While this phenomenon does not occur in English (but does in Japanese and other languages), an English example would be if the sentence “the genome of Oikopleura dioica is highly scrambled” could be rearranged to “highly scrambled Oikopleura dioica the genome of is” without a change in meaning. While genomic rearrangements are common to all species, and genome scrambling has been observed in a few species over a very long time, Oikopleura dioica surpasses what was previously thought possible.

Evolution at breakneck speed

The researchers compared the genetic sequences of the three lineages, which lead them to estimate that they shared a common ancestor around 25 million years ago, with the lineages from Barcelona and Osaka being more closely related than the Okinawa lineage, having diverged ~7 million years ago. For comparison, humans diverged from mice 75-90 million years ago.

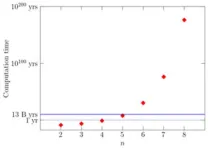

From their phylogenetic analyses, the researchers estimated the rate of genomic rearrangements for different species as a quantifiable measure for how quickly they evolve. From this, the researchers found that the rate for Oikopleura dioica is more than ten times higher than comparable species of Ciona sea squirts. As Dr. Michael J. Mansfield from the unit and co-first author on the paper puts it, “the Oikopleura is one of the fastest evolving animals in the world. Animals, especially chordates, don’t normally rearrange their genomes to this extent, at this speed.”

With all this genome scrambling taking place between the Oikopleura dioica lineages, from a genomic perspective it’s mystifying that they can retain such similar characteristics. “Our results suggest that while genomic organization is important, especially for something as complex as human beings, we should not forget the individual genes,” suggests Dr. Plessy. Studying genes and genomes can offer two different perspectives on the same phenomenon – as Dr. Mansfield explains it, “there are scientists studying anatomy and others who study individual neurons – but both are answering questions about the brain.”

Who's asking?

Genome scrambling poses important questions about evolution and classifying life into species. On the one hand, the researchers show that even if the three lineages of Oikopleura dioica are virtually identical morphologically and functionally, their genomes are extremely scrambled, which could suggest that they belong to different species, though the researchers stress that their intention is not to classify them here. On the other hand, the scrambled-yet-analogous gene expression could warn against an overreliance on genomics for classifying species.

Ultimately, however, “species don’t need us. If you remove humans, the animals are the same – it doesn’t matter how we classify them,” as Dr. Plessy phrases it. Instead, the concept of species is fluid, depending on whether it’s for conservation purposes, for legislation, as a microbiologist or a zoologist, or whatever the reason is. “The question ‘what is a species?’ can be answered with another question: why do you ask?”

For Dr. Plessy, Dr. Mansfield, and their collaborators around the world, this paper is the culmination of a long process of cultivating different lineages of Oikopleura dioica and developing bioinformatic tools capable of analyzing their chaotic genomes. Professor Nicholas Luscombe, head of the unit at OIST, is optimistic about the research potential of the study and the animals: “we initially assumed that all Oikopleura would have similar genomes, but we were amazed to see such huge differences with so much scrambling between them. We want to use Oikopleura to learn more about the nature of genomic rearrangements. I am excited that we have so much yet to learn!”

This is just the beginning – the researchers are far from done studying the enigmatic zooplankton: “we have already learned so much from the Oikopleura, but we have yet to explore the full extent of the diversity of the species at a global scale,” as Dr. Plessy explains. Dr. Mansfield quotes the great biologist Jacques Monod with “what’s true for E. coli is true for the elephant” – with the tools developed for this study, the teams can now turn their attention to other species. “We went into this thinking that all Oikopleura dioica were the same, but we have shown the opposite. How often is that true for other species, and how much more is there to know about the mechanisms of genome scrambling?”

END

Oikopleura who? Species identity crisis in the genome community

Genomic analysis of a widespread species of zooplankton questions our assumptions about speciation and gene regulation

2024-05-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Developed compiler acceleration technology for quantum computers

2024-05-09

[Highlights]

- Developed a new compilation method to generate optimal sequences to be executed on quantum computers

- The new method is based on a probabilistic approach and reduces the time to search for the optimal sequence by several orders of magnitude.

- Expected to contribute to quantum information processing at quantum nodes that support the quantum internet

[Abstract]

The National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT, President: TOKUDA Hideyuki, Ph.D.), RIKEN (President: GONOKAMI Makoto, Ph.D.), Tokyo University of Science (President: Dr. ISHIKAWA Masatoshi), and the University of Tokyo (President: FUJII Teruo, Ph.D.) succeeded ...

Report: Governments falling short on promises of effective biodiversity protection

2024-05-09

WASHINGTON— A new analysis of the world’s largest 100 marine protected areas (MPAs) published today in Conservation Letters suggests that governments are falling short on delivering the promise of effective biodiversity protection due to slow implementation of management strategies and failure to restrict the most impactful activities.

The assessment, titled “Ocean protection quality is lagging behind quantity: Applying a scientific framework to assess real marine protected area progress ...

Study shows how night shift work can raise risk of diabetes, obesity

2024-05-09

Just a few days on a night shift schedule throws off protein rhythms related to blood glucose regulation, energy metabolism and inflammation, processes that can influence the development of chronic metabolic conditions.

The finding, from a study led by scientists at Washington State University and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, provides new clues as to why night shift workers are more prone to diabetes, obesity and other metabolic disorders.

“There are processes tied to the master biological clock in our brain that are saying that day ...

Eleventh Nano Research Award goes to Louis E. Brus and Moungi Bawendi

2024-05-09

Recently, Nano Research announced awardees of the 11th Nano Research Award. Two outstanding scientists, Professor Louis E. Brus of Columbia University and Professor Moungi Bawendi of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, have been awarded this honor.

The Nano Research Award, established by the journal Nano Research together with Tsinghua University Press (TUP) and Springer Nature in 2013, aims to recognize outstanding contributions to nano research by an individual scientist. The winner is selected by the Award Committee ...

Traffic injuries to low-income NYC residents fell 30% in first five years of ‘vision zero’ road safety program, NYU study finds

2024-05-09

Among New Yorkers with low incomes, the “Vision Zero” initiative to stem roadway crashes resulted in a marked, 30% reduction in traffic injuries of varying severity from early 2014 – when the city government launched the program – until 2019, according to a new study conducted at New York University.

The study, scheduled for publication May 8 at 4:00 p.m. (ET) in the American Journal of Public Health, revealed this trend of improved safety by comparing Medicaid-covered injury ...

AI tool instantly assesses self-harm risk

2024-05-09

Suicidality hit new record high in U.S. in 2022

New tool was 92% effective at predicting four variables related to self-harm

AI uses a small set of judgment and contextual variables as opposed to big data, and strongly supports the hypothesis of a standard model of mind

EVANSTON, Ill. --- A new assessment tool that leverages powerful artificial intelligence was able to predict whether participants exhibited suicidal thoughts and behaviors using a quick and simple combination of variables.

Developed by researchers at Northwestern University, the University of Cincinnati (UC), Aristotle ...

An epigenome editing toolkit to dissect the mechanisms of gene regulation

2024-05-09

Understanding how genes are regulated at the molecular level is a central challenge in modern biology. This complex mechanism is mainly driven by the interaction between proteins called transcription factors, DNA regulatory regions, and epigenetic modifications – chemical alterations that change chromatin structure. The set of epigenetic modifications of a cell’s genome is referred to as the epigenome.

In a study just published in Nature Genetics, scientists from the Hackett Group at EMBL Rome have developed a modular epigenome editing platform – a system to program epigenetic modifications at any location in the genome. The system allows scientists to study the impact ...

How aging clocks tick

2024-05-09

Aging clocks can measure the biological age of humans with high precision. Biological age can be influenced by environmental factors such as smoking or diet, thus deviating from the chronological age that is calculated using the date of birth. The precision of these aging clocks suggests that the aging process follows a programme. Scientists David Meyer and Professor Dr Björn Schumacher at CECAD, the Cluster of Excellence Cellular Stress Responses in Aging-Associated Diseases of the University of Cologne, have now discovered that aging clocks actually measure the increase in stochastic changes in cells. The study ‘Aging clocks based on accumulating stochastic variation’ ...

miR-146a rs2910164 C>G Polymorphism and Wilms tumor susceptibility in Eastern Chinese children

2024-05-09

Background and objectives

Wilms tumor is the most common renal malignancy in children. miR-146a, a highly conserved small noncoding RNA, plays a critical role in various human diseases. Increasing studies have suggested that rs2910164 C>G polymorphism in miR-146a is associated with susceptibility to cancers. However, miR-146a rs2910164 C>G polymorphism influence on Wilms tumor remains unknown. The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between miR-146a rs2910164 C>G polymorphism and Wilms ...

Simple “swish-and-spit” oral rinse could provide early screening for gastric cancer

2024-05-09

BETHESDA, MD. (May 9, 2024) — A simple oral rinse could provide early detection of gastric cancer, the fourth-leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide, according to a study scheduled for presentation at Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2024.

“In the cancer world, if you find patients after they've developed cancer, it's a little too late,” said Shruthi Reddy Perati, MD, author and general surgery resident at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson School of Medicine. “The ideal time to try to prevent ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

A genetic brake that forms our muscles

CHEST announces first class of certified critical care advanced practice providers awarded CCAPP Designation

Jeonbuk National University researchers develop an innovative prussian-blue based electrode for effective and efficient cesium removal

Self-organization of cell-sized chiral rotating actin rings driven by a chiral myosin

Report: US history polarizes generations, but has potential to unite

Tiny bubbles, big breakthrough: Cracking cancer’s “fortress”

A biological material that becomes stronger when wet could replace plastics

Glacial feast: Seals caught closer to glaciers had fuller stomachs

Get the picture? High-tech, low-cost lens focuses on global consumer markets

Antimicrobial resistance in foodborne bacteria remains a public health concern in Europe

Safer batteries for storing energy at massive scale

How can you rescue a “kidnapped” robot? A new AI system helps the robot regain its sense of location in dynamic, ever-changing environments

Brainwaves of mothers and children synchronize when playing together – even in an acquired language

A holiday to better recovery

Cal Poly’s fifth Climate Solutions Now conference to take place Feb. 23-27

Mask-wearing during COVID-19 linked to reduced air pollution–triggered heart attack risk in Japan

Achieving cross-coupling reactions of fatty amide reduction radicals via iridium-photorelay catalysis and other strategies

Shorter may be sweeter: Study finds 15-second health ads can curb junk food cravings

Family relationships identified in Stone Age graves on Gotland

Effectiveness of exercise to ease osteoarthritis symptoms likely minimal and transient

Cost of copper must rise double to meet basic copper needs

A gel for wounds that won’t heal

Iron, carbon, and the art of toxic cleanup

Organic soil amendments work together to help sandy soils hold water longer, study finds

Hidden carbon in mangrove soils may play a larger role in climate regulation than previously thought

Weight-loss wonder pills prompt scrutiny of key ingredient

Nonprofit leader Diane Dodge to receive 2026 Penn Nursing Renfield Foundation Award for Global Women’s Health

Maternal smoking during pregnancy may be linked to higher blood pressure in children, NIH study finds

New Lund model aims to shorten the path to life-saving cell and gene therapies

Researchers create ultra-stretchable, liquid-repellent materials via laser ablation

[Press-News.org] Oikopleura who? Species identity crisis in the genome communityGenomic analysis of a widespread species of zooplankton questions our assumptions about speciation and gene regulation