(Press-News.org) By Rose Miyatsu, UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute

Although you may not appreciate them, or have even heard of them, throughout your body, countless microscopic machines called spliceosomes are hard at work. As you sit and read, they are faithfully and rapidly putting back together the broken information in your genes by removing sequences called “introns” so that your messenger RNAs can make the correct proteins needed by your cells.

Introns are perhaps one of our genome’s biggest mysteries. They are DNA sequences that interrupt the sensible protein-coding information in your genes, and need to be "spliced out.” The human genome has hundreds of thousands of introns, about 7 or 8 per gene, and each is removed by a specialized RNA protein complex called the “spliceosome” that cuts out all the introns and splices together the remaining coding sequences, called exons. How this system of broken genes and the spliceosome evolved in our genomes is not known.

Over his long career, Manny Ares, UC Santa Cruz distinguished professor of molecular, cellular, and developmental biology, has made it his mission to learn as much about RNA splicing as he can.

“I’m all about the spliceosome,” Ares said. “I just want to know everything the spliceosome does – even if I don’t know why it is doing it.”

In a new paper published in the journal Genes and Development, Ares reports on a surprising discovery about the spliceosome that could tell us more about the evolution of different species and the way cells have adapted to the strange problem of introns. The authors show that after the spliceosome is finished splicing the mRNA, it remains active and can engage in further reactions with the removed introns.

This discovery provides the strongest indication we have so far that spliceosomes could be able to reinsert an intron back into the genome in another location. This is an ability that spliceosomes were not previously believed to possess, but which is a common characteristic of “Group II introns,” distant cousins of the spliceosome that exist primarily in bacteria.

The spliceosome and Group II introns are believed to share a common ancestor that was responsible for spreading introns throughout the genome, but while Group II introns can splice themselves out of RNA and then directly back into DNA, the “spliceosomal introns” that are found in most higher-level organisms require the spliceosome for splicing and were not believed to be reinserted back into DNA. However, Ares’s lab’s finding indicates that the spliceosome might still be reinserting introns into the genome today. This is an intriguing possibility to consider because introns that are reintroduced into DNA add complexity to the genome, and understanding more about where these introns come from could help us to better understand how organisms continue to evolve.

Building on an interesting discovery

An organism’s genes are made of DNA, in which four bases, adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T) are ordered in sequences that code for biological instructions, like how to make specific proteins the body needs. Before these instructions can be read, the DNA gets copied into RNA by a process known as transcription, and then the introns in that RNA have to be removed before a ribosome can translate it into actual proteins.

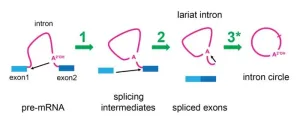

The spliceosome removes introns using a two-step process that results in the intron RNA having one of its ends joined to its middle, forming a circle with a tail that looks like a cowboy's "lariat,” or lasso. This appearance has led to them being named “lariat introns.” Recently, researchers at Brown University who were studying the locations of the joining sites in these lariats made an odd observation - some introns were actually circular instead of lariat shaped.

This observation immediately got Ares’s attention. Something seemed to be interacting with the lariat introns after they were removed from the RNA sequence to change their shape, and the spliceosome was his main suspect.

“I thought that was interesting because of this old, old idea about where introns came from,” Ares said. “There is a lot of evidence that the RNA parts of the spliceosome, the snRNAs, are closely related to Group II introns.”

Because the chemical mechanism for splicing is very similar between the spliceosomes and their distant cousins, the Group II introns, many researchers have theorized that when the process of self-splicing became too inefficient for Group II introns to reliably complete on their own, parts of these introns evolved to become the spliceosome. While Group II introns were able to insert themselves directly back into DNA, however, spliceosomal introns that required the help of spliceosomes were not thought to be inserted back into DNA.

“One of the questions that was sort of missing from this story in my mind was, is it possible that the modern spliceosome is still able to take a lariat intron and insert it somewhere in the genome?” Ares said. “Is it still capable of doing what the ancestor complex did?”

To begin to answer this question, Ares decided to investigate whether it was indeed the spliceosome that was making changes to the lariat introns to remove their tails. His lab slowed the splicing process in yeast cells, and discovered that after the spliceosome released the mRNA that it had finished splicing introns from, it hung onto intron lariats and reshaped them into true circles. The Ares lab was able to reanalyze published RNA sequencing data from human cells and found that human spliceosomes also had this ability.

“We are excited about this because while we don't know what this circular RNA might do, the fact that the spliceosome is still active suggests it may be able to catalyze the insertion of the lariat intron back into the genome,” Ares said.

If the spliceosome is able to reinsert the intron into DNA, this would also add significant weight to the theory that spliceosomes and Group II introns shared a common ancestor long ago.

Testing a theory

Now that Ares and his lab have shown that the spliceosome has the catalytic ability to hypothetically place introns back into DNA like their ancestors did, the next step is for the researchers to create an artificial situation in which they “feed” a DNA strand to a spliceosome that is still attached to a lariat intron and see if they can actually get it to insert the intron somewhere, which would present “proof of concept” for this theory.

If the spliceosome is able to reinsert introns into the genome, it is likely to be a very infrequent event in humans, because the human spliceosomes are in incredibly high demand and therefore do not have much time to spend with removed introns. In other organisms where the spliceosome isn't as busy, however, the reinsertion of introns may be more frequent. Ares is working closely with UCSC Biomolecular Engineering Professor Russ Corbett-Detig, who has recently led a systematic and exhaustive hunt for new introns in the available genomes of all intron-containing species that was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) last year.

The paper in PNAS showed that intron “burst” events far back in evolutionary history likely introduced thousands of introns into a genome all at once. Ares and Corbett-Detig are now working to recreate a burst event artificially, which would give them insight into how genomes reacted when this happened.

Ares said that his cross-disciplinary partnership with Corbett-Detig has opened the doors for them to really dig into some of the biggest mysteries about introns that would probably be impossible for them to understand fully without their combined expertise.

“It is the best way to do things,” Ares said. “When you find someone who has the same kind of questions in mind but a different set of methods, perspectives, biases, and weird ideas, that gets more exciting. That makes you feel like you can break out and solve a problem like this, which is very complex.”

Related links:

Ares Laboratory

UC Santa Cruz Department of Molecular, Cell, and Developmental Biology END

UC Santa Cruz study discovers cellular activity that hints recycling is in our DNA

New research shows that 'spliceosomes' might reinsert problematic gene sequences after removing them

2024-05-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A retrospective look at Human Computer Interaction - free public lecture by Professor Manolya Kavakli

2024-05-10

Professor Manolya Kavakli is an expert in gamification

Her talk will examine the complex relationship between humans, computers and tech

She will examine how digital developments have the potential to improve lives and modernise industry.

The latest inaugural lecture at Aston University will look at the complex relationship between humans, computers and technology.

Professor Manolya Kavakli will discuss progress so far and offer insights into how to ease into digital transformation for the challenges that lie ahead.

The professor is an expert in gamification, the process of using elements of gaming in non-gaming situations such as learning and training.

She ...

Reducing prejudice in war zones proves challenging

2024-05-10

There are 62.5 million internally displaced persons worldwide, according to 2022 data by the UNHCR, the United Nations Refugee Agency. These individuals were forced to leave their homes but remain in the same country.

Prior research has shown that internally displaced persons often experience prejudice and discrimination, as residents in their new locale fear that the migrants may be insurgents or criminals, or compete for jobs.

Now, a new Dartmouth study involving Afghanistan indicates that changing such attitudes is an uphill battle. Given the decades of fighting there, Afghanistan has had one of the largest populations ...

Chapman professor contributes to breakthrough hemostasis and wound healing research

2024-05-10

A breakthrough study, published in Science Translational Medicine, features a biomedical engineering innovation with the potential to transform trauma care and surgical practices. Chapman University’s Fowler School of Engineering Founding Dean and Professor, Andrew Lyon, is a member of this multidisciplinary, multi-university scientific research team developing platelet-like particles that integrate into the body’s clotting pathways to stop hemorrhage. Sanika Pandit, an alumna of Chapman University, is also among the 15 authors in this research.

Addressing a longstanding gap in surgical and trauma care, this advancement holds potential for patient implementation. Patients ...

Melanoma in darker skin tones: Race and sex play a role, Mayo study finds

2024-05-10

ROCHESTER, Minn. — Melanoma, an aggressive form of skin cancer that accounts for 75% of all skin-cancer-related deaths, is often detected later in people with darker skin complexions — and the consequences can be devastating, a Mayo Clinic study reveals.

While melanoma may be found less frequently in people with darker complexions than fair ones, this potentially serious form of cancer can strike anyone. The study, which consisted of 492,597 patients with melanoma, suggests that added vigilance in early screening is particularly needed for Black men, whose cancers ...

Visual experiences unique to early infancy provide building blocks of human vision, IU study finds

2024-05-10

What do infants see? What do they look at? The answers to these questions are very different for the youngest babies than they are for older infants, children and adults. Characterized by a few high-contrast edges in simple patterns, these early scenes also contain the very materials needed to build a strong foundation for human vision.

That is the finding of a new study, “An edge-simplicity bias in the visual input to young infants,” published on May 10 in Science Advances by IU researchers Erin Anderson, Rowan Candy, Jason Gold and Linda Smith.

“The starting ...

Clues from deep magma reservoirs could improve volcanic eruption forecasts

2024-05-10

New research into molten rock 20km below the Earth’s surface could help save lives by improving the prediction of volcanic activity.

Volcanic eruptions pose significant hazards, with devastating impacts on both people living nearby and the environment.

They are currently predicted based on activity of the volcano itself and the upper few kilometres of crust beneath it, which contains molten rock potentially ready to erupt.

However, new research highlights the importance of searching for ...

Scientists unlock key to breeding ‘carbon gobbling’ plants with a major appetite

2024-05-10

The discovery of how a critical enzyme “hidden in nature’s blueprint” works sheds new light on how cells control key processes in carbon fixation, a process fundamental for life on Earth.

The discovery, made by scientists from The Australian National University (ANU) and the University of Newcastle (UoN), could help engineer climate resilient crops capable of sucking carbon dioxide from the atmosphere more efficiently, helping to produce more food in the process.

The research, published in Science Advances, demonstrates a previously unknown function of an enzyme called carboxysomal carbonic anhydrase (CsoSCA), which is found in cyanobacteria – also called ...

Hubble celebrates the 15th anniversary of servicing Mission 4

2024-05-10

Fifteen years ago, human hands touched NASA's Hubble Space Telescope for the last time.

As astronauts performed finishing tasks on the telescope during its final servicing mission in May 2009, they knew they had successfully concluded one of the most challenging and ambitious series of spacewalks ever conducted. But they couldn’t have known at the time what an impact they had truly made.

“I had high hopes that Hubble would last at least five years more, and maybe even a little more to overlap with Webb,” said astronaut and former associate administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate John ...

Hints of a possible atmosphere around a rocky exoplanet

2024-05-10

55 Cancri e is one of five known planets orbiting a Sun-like star in the constellation Cancer. With a diameter nearly twice that of Earth and a density slightly greater, the planet is classified as a super-Earth: larger than Earth, smaller than Neptune, and similar in composition to the rocky planets in our solar system.

Brice-Olivier Demory from the Center for Space and Habitability CSH of the University of Bern and member of the NCCR PlanetS is co-author of the study that has just been published in Nature. He ...

UVA Data Art Competition draws more than 130 submissions and announces winners

2024-05-10

Data has the power to tell captivating stories and reveal hidden insights, often in aesthetically compelling ways.

In celebration of this, the University of Virginia’s School of Data Science hosted an art competition to commemorate the opening of its new building and to invite participants from all over the world to tell unique stories by transforming raw data into art. The School received more than 130 submissions from nine countries, far exceeding expectations for an inaugural competition.

After selecting eight finalists from a wide range of artistic formats, the winners were announced during ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

Joint and independent associations of gestational diabetes and depression with childhood obesity

Spirituality and harmful or hazardous alcohol and other drug use

New plastic material could solve energy storage challenge, researchers report

Mapping protein production in brain cells yields new insights for brain disease

Exposing a hidden anchor for HIV replication

Can Europe be climate-neutral by 2050? New monitor tracks the pace of the energy transition

Major heart attack study reveals ‘survival paradox’: Frail men at higher risk of death than women despite better treatment

Medicare patients get different stroke care depending on plan, analysis reveals

Polyploidy-induced senescence may drive aging, tissue repair, and cancer risk

Study shows that treating patients with lifestyle medicine may help reduce clinician burnout

Experimental and numerical framework for acoustic streaming prediction in mid-air phased arrays

Ancestral motif enables broad DNA binding by NIN, a master regulator of rhizobial symbiosis

Macrophage immune cells need constant reminders to retain memories of prior infections

Ultra-endurance running may accelerate aging and breakdown of red blood cells

Ancient mind-body practice proven to lower blood pressure in clinical trial

SwRI to create advanced Product Lifecycle Management system for the Air Force

Natural selection operates on multiple levels, comprehensive review of scientific studies shows

Developing a national research program on liquid metals for fusion

AI-powered ECG could help guide lifelong heart monitoring for patients with repaired tetralogy of fallot

Global shark bites return to average in 2025, with a smaller proportion in the United States

Millions are unaware of heart risks that don’t start in the heart

What freezing plants in blocks of ice can tell us about the future of Svalbard’s plant communities

A new vascularized tissueoid-on-a-chip model for liver regeneration and transplant rejection

Augmented reality menus may help restaurants attract more customers, improve brand perceptions

[Press-News.org] UC Santa Cruz study discovers cellular activity that hints recycling is in our DNANew research shows that 'spliceosomes' might reinsert problematic gene sequences after removing them