(Press-News.org) A World Health Organization Essential Medicine, ketamine is widely used at varying doses for sedation, pain control, general anesthesia and as a therapy for treatment-resistant depression. While scientists know its target in brain cells and have observed how it affects brain-wide activity, they haven’t known entirely how the two are connected. A new study by a research team spanning four Boston-area institutions uses computational modeling of previously unappreciated physiological details to fill that gap and offer new insights into how ketamine works.

“This modeling work has helped decipher likely mechanisms through which ketamine produces altered arousal states as well as its therapeutic benefits for treating depression,” co-senior author Emery N. Brown, Edward Hood Taplin Professor of Computational Neuroscience and Medical Engineering at The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT, as well as an anesthesiologist at MGH and a Professor at Harvard Medical School.

The researchers from MIT, Boston University, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard University said the predictions of their model, published May 20 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could help physicians make better use of the drug.

“When physicians understand what's mechanistically happening when they administer a drug, they can possibly leverage that mechanism and manipulate it,” said study lead author Elie Adam, a Research Scientist at MIT who will soon join the Harvard Medical School faculty and launch a lab at MGH. “They gain a sense of how to enhance the good effects of the drug and how to mitigate the bad ones.”

Blocking the door

The core advance of the study involved biophysically modeling what happens when ketamine blocks the “NMDA” receptors in the brain’s cortex—the outer layer where key functions such as sensory processing and cognition take place. Blocking the NMDA receptors modulates the release of excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate.

When the neuronal channels (or doorways) regulated by the NMDA receptors open, they typically close slowly (like a doorway with a hydraulic closer that keeps it from slamming), allowing ions to go in and out of neurons, thereby regulating their electrical properties, Adam said. But, the channels of the receptor can be blocked by a molecule. Blocking by magnesium helps to naturally regulate ion flow. Ketamine, however, is an especially effective blocker.

Blocking slows the voltage build-up across the neuron’s membrane that eventually leads a neuron to “spike,” or send an electrochemical message to other neurons. The NMDA doorway becomes unblocked when the voltage gets high. This interdependence between voltage, spiking and blocking can equip NMDA receptors with faster activity than its slow closing speed might suggest. The team’s model goes further than ones before by representing how ketamine’s blocking and unblocking affect neural activity.

“Physiological details that are usually ignored can sometimes be central to understanding cognitive phenomena,” said co-corresponding author Nancy Kopell, a professor of math at BU. “The dynamics of NMDA receptors have more impact on network dynamics than has previously been appreciated.”

With their model, the scientists simulated how different doses of ketamine affecting NMDA receptors would alter the activity of a model brain network. The simulated network included key neuron types found in the cortex: one excitatory type and two inhibitory types. It distinguishes between “tonic” interneurons that tamp down network activity and “phasic” interneurons that react more to excitatory neurons.

The team’s simulations successfully recapitulated the real brain waves that have been measured via EEG electrodes on the scalp of a human volunteer who received various ketamine doses and the neural spiking that has been measured in similarly treated animals that had implanted electrode arrays. At low doses, ketamine increased brain wave power in the fast gamma frequency range (30-40 Hz). At the higher doses that cause unconsciousness, those gamma waves became periodically interrupted by “down” states where only very slow frequency delta waves occur. This repeated disruption of the higher frequency waves is what can disrupt communication across the cortex enough to disrupt consciousness.

But how? Key findings

Importantly, through simulations, they explained several key mechanisms in the network that would produce exactly these dynamics.

The first prediction is that ketamine can disinhibit network activity by shutting down certain inhibitory interneurons. The modeling shows that natural blocking and unblocking kinetics of NMDA-receptors can let in a small current when neurons are not spiking. Many neurons in the network that are at the right level of excitation would rely on this current to spontaneously spike. But when ketamine impairs the kinetics of the NMDA receptors, it quenches that current, leaving these neurons suppressed. In the model, while ketamine equally impairs all neurons, it is the tonic inhibitory neurons that get shut down because they happen to be at that level of excitation. This releases other neurons, excitatory or inhibitory from their inhibition allowing them to spike vigorously and leading to ketamine’s excited brain state. The network’s increased excitation can then enable quick unblocking (and reblocking) of the neurons’ NMDA receptors, causing bursts of spiking.

Another prediction is that these bursts become synchronized into the gamma frequency waves seen with ketamine. How? The team found that the phasic inhibitory interneurons become stimulated by lots of input of the neurotransmitter glutamate from the excitatory neurons and vigorously spike, or fire. When they do, they send an inhibitory signal of the neurotransmitter GABA to the excitatory neurons that squelches the excitatory firing, almost like a kindergarten teacher calming down a whole classroom of excited children. That stop signal, which reaches all the excitatory neurons simultaneously, only lasts so long, ends up synchronizing their activity, producing a coordinated gamma brain wave.

“The finding that an individual synaptic receptor (NMDA) can produce gamma oscillations and that these gamma oscillations can influence network-level gamma was unexpected,” said co-corresponding author Michelle McCarthy, a research assistant professor of math at BU. “This was found only by using a detailed physiological model of the NMDA receptor. This level of physiological detail revealed a gamma time scale not usually associated with an NMDA receptor.”

So what about the periodic down states that emerge at higher, unconsciousness-inducing ketamine doses? In the simulation, the gamma-frequency activity of the excitatory neurons can’t be sustained for too long by the impaired NMDA-receptor kinetics. The excitatory neurons essentially become exhausted under GABA inhibition from the phasic interneurons. That produces the down state. But then, after they have stopped sending glutamate to the phasic interneurons, those cells stop producing their inhibitory GABA signals. That enables the excitatory neurons to recover, starting a cycle anew.

Antidepressant connection?

The model makes another prediction that might help explain how ketamine exerts its antidepressant effects. It suggests that the increased gamma activity of ketamine could entrain gamma activity among neurons expressing a peptide called VIP. This peptide has been found to have health promoting effects, such as reducing inflammation, that last much longer than ketamine’s effects on NMDA receptors. The research team proposes that the entrainment of these neurons under ketamine could increase the release of the beneficial peptide, as observed when these cells are stimulated in experiments. This also hints at therapeutic features of ketamine that may go beyond anti-depressant effects. The research team acknowledges, however, that this connection is speculative and awaits specific experimental validation.

“The understanding that the sub cellular details of the NMDA receptor can lead to increased gamma oscillations was the basis for a new theory about how ketamine may work for treating depression,” Kopell said.

Additional co-authors of the study are Marek Kowalski, Oluwaseun Akeju, and Earl K. Miller.

The JPB Foundation, The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, The Simons Center for The Social Brain, the National Institutes of Health, George J. Elbaum (MIT ’59, SM ’63, PhD ’67), Mimi Jensen, Diane B. Greene (MIT, SM ’78), Mendel Rosenblum, Bill Swanson, and annual donors to the Anesthesia Initiative Fund supported the research.

END

Study models how ketamine’s molecular action leads to its effects on the brain

New research addresses a gap in understanding how ketamine’s impact on individual neurons leads to pervasive and profound changes in brain network function.

2024-05-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A diaspora-based model of human migration

2024-05-21

How do migrants choose their destinations? Existing models, known as “gravity models,” use population size and travel distance as explanatory variables—and often fail, especially at the neighborhood scale. Many migrants prefer to move to a location near friends, family, or co-nationals. This pattern might be partly driven by factors that repeat (such as the cost of living) and partly driven by homophily, the tendency to interact with similar others. Early migrants tend to reduce uncertainty and provide information for later arrivals. Building on these observations, Rafael Prieto-Curiel and colleagues construct a migration model based on the power of the diaspora to ...

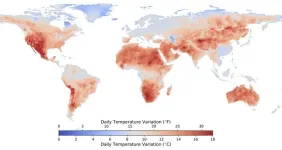

Black and Hispanic Americans experience wider temperature swings

2024-05-21

Extreme heat can harm human health, but so can temperature extreme swings. Large daily temperature variation (DTV) has been associated with elevated mortality in studies around the world. Trees and other vegetation can lower DTV, as trees reduce temperature through transpiration during the day and also trap long-wave radiation in the atmosphere under the canopy at night, increasing temperature. But green space is not equally distributed in most cities. Shengjie Liu and Emily Smith-Greenaway examined inequality in DTV exposure in the US, using monthly nighttime and daytime land surface temperature data from satellites. ...

Gamers say they hate ‘smurfing,’ but admit they do it

2024-05-21

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Online video game players believe the behavior known as “smurfing” is generally wrong and toxic to the gaming community – but most admit to doing it and say some reasons make the behavior less blameworthy, new research finds.

The new study suggests that debates about toxicity in gaming may sometimes be more complex and nuanced than is often acknowledged, according to the researchers.

Online video games use what are called “matchmaking systems” to pair players based on skill. “Smurfing” is when players cheat these systems by creating new accounts so that they can play against people lower ...

How immune cells recognize the abnormal metabolism of cancer cells

2024-05-21

When cells become tumor cells, their metabolism changes fundamentally. Researchers at the University of Basel and the University Hospital Basel have now demonstrated that this change leaves traces that could provide targets for cancer immunotherapies.

Cancer cells function in turbo mode: Their metabolism is programmed for rapid proliferation, whereby their genetic material is also constantly copied and translated into proteins. As researchers led by Professor Gennaro De Libero from the University of Basel and the University ...

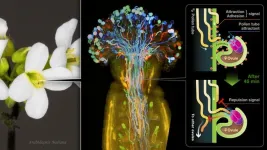

How plants mate for life and repel other suitors

2024-05-21

A group of scientists from Nagoya University in Japan has used a specialized microscopic technique to observe the internal reproduction process of the Arabidopsis plant. Their findings, published in EMBO Reports, reveal the mechanism behind a female flower selectively attracting a single male counterpart. These findings provide insights that may help optimize seed production and improve agricultural breeding practices.

Angiosperms, commonly referred to as flowering plants, have male and female reproductive organs. In the process of plant reproduction, when a pollen grain that ...

3D printing robot uses AI machine learning for US Army research

2024-05-21

Inside a lab in Boston University’s College of Engineering, a robot arm drops small, plastic objects into a box placed perfectly on the floor to catch them as they fall. One by one, these tiny structures—feather-light, cylindrical pieces, no bigger than an inch tall—fill the box. Some are red, others blue, purple, green, or black.

Each object is the result of an experiment in robot autonomy. On its own, learning as it goes, the robot is searching for, and trying to make, an object with the most efficient ...

Ruptured Achilles tendon shows faster repair amid plasma irradiation treatment

2024-05-21

What is the largest ligament in the human body? It might surprise some people that it is the Achilles tendon. Even though it is also considered the toughest ligament, the Achilles tendon can rupture, with many such injuries involving sports enthusiasts in their 30s or 40s. Surgery might be required, and a prolonged period of rest, immobilization, and treatment can be difficult to endure.

Seeking to shorten the recovery time, a research team led by Osaka Metropolitan University Graduate School of Medicine’s Katsumasa Nakazawa, a graduate student in the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Associate Professor ...

Screen time not the main factor making parent-child interactions worse, study finds

2024-05-21

Technology use is at an all-time high and understanding how this impacts daily life is crucial. When it comes to parent-child interactions, scientists have coined the term ‘technoference,’ meaning technology interference. It occurs when parent-child interaction and communication are disrupted by the use of digital devices.

But is distraction caused by digital devices more detrimental to parent-child interaction than when parental distraction comes from different sources? Researchers in Switzerland have investigated.

“In this study, we show that ...

Improving the effectiveness of earthquake early warning systems

2024-05-21

Mobile phones have become invaluable for receiving emergency alerts such as weather warnings, evacuation notices and notifications about missing persons. In Japan, where earthquakes are frequent, they are vital for delivering earthquake warnings and advising people to take protective actions beforehand. To deal with such situations promptly, the Earthquake Early Warning (EEW) system sends out notifications to areas expected to experience strong tremors by detecting primary seismic waves (P-waves) that arrive before the secondary waves (S-waves). However, the short time between receiving the notification and the arrival of S-waves ...

Addressing homelessness in older people

2024-05-21

Homelessness doesn’t only happen to young people but also affects older adults in growing numbers, write authors in an analysis in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal) that describes this emerging crisishttps://www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.231493.

People experiencing homelessness are considered older adults at age 50, as visible aging is often evident at younger ages in individuals experiencing homelessness compared with individuals who have secure housing. Individuals experiencing homelessness often develop chronic ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Stem cells from human baby teeth show promise for treating cerebral palsy

Chimps’ love for crystals could help us understand our own ancestors’ fascination with these stones

Vaginal estrogen therapy not linked to cancer recurrence in survivors of endometrial cancer

How estrogen helps protect women from high blood pressure

Breaking the efficiency barrier: Researchers propose multi-stage solar system to harness the full spectrum

A new name, a new beginning: Building a green energy future together

From algorithms to atoms: How artificial intelligence is accelerating the discovery of next-generation energy materials

Loneliness linked to fear of embarrassment: teen research

New MOH–NUS Fellowship launched to strengthen everyday ethics in Singapore’s healthcare sector

Sungkyunkwan University researchers develop next-generation transparent electrode without rare metal indium

What's going on inside quantum computers?: New method simplifies process tomography

This ancient plant-eater had a twisted jaw and sideways-facing teeth

Jackdaw chicks listen to adults to learn about predators

Toxic algal bloom has taken a heavy toll on mental health

Beyond silicon: SKKU team presents Indium Selenide roadmap for ultra-low-power AI and quantum computing

Sugar comforts newborn babies during painful procedures

Pollen exposure linked to poorer exam results taken at the end of secondary school

7 hours 18 mins may be optimal sleep length for avoiding type 2 diabetes precursor

Around 6 deaths a year linked to clubbing in the UK

Children’s development set back years by Covid lockdowns, study reveals

Four decades of data give unique insight into the Sun’s inner life

Urban trees can absorb more CO₂ than cars emit during summer

Fund for Science and Technology awards $15 million to Scripps Oceanography

New NIH grant advances Lupus protein research

New farm-scale biochar system could cut agricultural emissions by 75 percent while removing carbon from the atmosphere

From herbal waste to high performance clean water material: Turning traditional medicine residues into powerful biochar

New sulfur-iron biochar shows powerful ability to lock up arsenic and cadmium in contaminated soils

AI-driven chart review accurately identifies potential rare disease trial participants in new study

Paleontologist Stephen Chester and colleagues reveal new clues about early primate evolution

UF research finds a gentler way to treat aggressive gum disease

[Press-News.org] Study models how ketamine’s molecular action leads to its effects on the brainNew research addresses a gap in understanding how ketamine’s impact on individual neurons leads to pervasive and profound changes in brain network function.