(Press-News.org) The Epstein-Barr virus can cause a spectrum of diseases, including a range of cancers. Emerging data now show that inhibition of a specific metabolic pathway in infected cells can diminish latent infection and therefore the risk of downstream disease, as reported by researchers from the University of Basel and the University Hospital Basel in the journal Science.

Exactly 60 years ago, pathologist Anthony Epstein and virologist Yvonne Barr announced the discovery of a virus that has carried their names ever since. The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) made scientific history as the first virus proven to cause cancer in humans. Epstein and Barr isolated the pathogen, which is part of the herpesvirus family, from tumor tissue and demonstrated its cancer-causing potential in subsequent experiments.

Most people are carriers of EBV: 90% of the adult population are infected with the virus, usually experiencing no symptoms and no resulting illness. Around 50% become infected before the age of five, but many people don’t catch it until adolescence. Acute infection with the virus can cause glandular fever — also known as “kissing disease” — and can put infected individuals out of action for several months. In addition to its cancerogenic properties, the pathogen is also suspected to be involved in the development of autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis.

As yet, no drug or approved vaccination can specifically thwart EBV within the body. Now, a research group from the University of Basel and the University Hospital Basel has reported a promising starting point for putting the brakes on EBV. Their results have been published in the journal Science.

EBV hijacks the metabolism of infected cells

Researchers led by Professor Christoph Hess have deciphered how the immune cells infected with EBV —the so-called B cells — are reprogrammed. Known as “transformation,” this process is necessary for the infection to become chronic and cause subsequent diseases such as cancer. Specifically, the team discovered that the virus triggers the infected cell to ramp up the production of an enzyme known as IDO1. This ultimately leads to greater energy production by the power plants of infected cells: the mitochondria. In turn, this additional energy is needed for the increased metabolism and the rapid proliferation of B cells reprogrammed by EBV in this way.

Clinically, the researchers focused on a group of patients who had developed EBV-triggered blood cancer following organ transplantation. To prevent a transplanted organ from being rejected, it is necessary to weaken the immune system using medications. This, in turn, makes it easier for EBV to gain the upper hand and cause blood cancer, referred to as post-transplant lymphoma.

In the paper, which has now been published, the researchers were able to show that EBV upregulates the enzyme IDO1 already months before post-transplant lymphoma is diagnosed. This finding may help to develop biomarkers for the disease.

Second chance for a failed drug

“Previously, IDO1 inhibitors have been developed in the hope that they could help to treat established cancer — which has unfortunately turned out not to be the case. In other words, there are already clinically tested inhibitors against this enzyme,” explains Christoph Hess. Accordingly, this class of drugs might now receive a second chance in applications aimed at dampening EBV infection and thereby tackling EBV-associated diseases. Indeed, in experiments with mice, IDO1 inhibition with these drugs reduced the transformation of B cells and therefore the viral load and the development of lymphoma.

“In transplant patients, it’s standard practice to use drugs against various viruses. Until now, there’s been nothing specific for preventing or treating Epstein-Barr virus associated disease,” says Hess.

END

New approach to Epstein-Barr virus and resulting diseases

2024-05-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Tracking the cellular and genetic roots of neuropsychiatric disease

2024-05-23

New Haven, Conn. – A new analysis has revealed detailed information about genetic variation in brain cells that could open new avenues for the targeted treatment of diseases such as schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease.

The findings, reported May 23 in Science, were the result of a multi-institutional collaboration known as PsychENCODE, founded in 2015 by the National Institutes of Health, which seeks new understandings of genomic influences on neuropsychiatric disease. The study was published alongside related studies in Science, Science Advances, and Science ...

Pioneering new study uncovers insights into PTSD & major depressive disorder

2024-05-23

AUSTIN, Texas — Stress-related disorders like post-traumatic stress disorder and clinical depression are complex conditions influenced by both genetics and our environment. Despite significant research, the molecular mechanisms behind these disorders have remained elusive. However, researchers at Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin have broken new ground with a study that sheds light on the intricate differences occurring in the brains of people with PTSD and depression compared to neurotypical controls. The study, published this week in Science, could provide potential avenues for novel therapeutics and biomarkers.

“Understanding why some people develop ...

Two new studies by Mount Sinai researchers in science offer key insights into the origins and potential treatment of mental health disorders

2024-05-23

Working under the umbrella of the PsychENCODE Consortium, the mental health research project established in 2015 by the National Institutes of Health, a team of Mount Sinai scientists has uncovered important new insights into the molecular biology of neuropsychiatric disease through two new studies published in a special issue of Science on Friday, May 24. These investigations, conducted with colleagues from other major research centers, involve the largest single-cell analysis to date of the brains of people with schizophrenia, and a first-of-its-kind ...

Sequencing of the developing human brain uncovers hundreds of thousands of new gene transcripts

2024-05-23

A team led by researchers at UCLA and the University of Pennsylvania has produced a first-of-its kind catalog of gene-isoform variation in the developing human brain. This novel dataset provides crucial insights into the molecular basis of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric brain disorders and paves the way for targeted therapies.

The research, published in Science, also details how transcript expression varies by cell type and maturity, finding that changing gene-isoform expression levels can help ...

Carnegie Mellon University researchers to tackle carbon use, sustainability through NSF expeditions in computing awards

2024-05-23

Researchers from Carnegie Mellon University's School of Computer Science will contribute to two multi-institution research initiatives aimed at reducing the use of carbon and creating sustainable computing.

The projects recently received funding through the U.S. National Science Foundation's (NSF) Expeditions in Computing Awards program, which is providing $36 million to three projects selected for their potential to revolutionize computing and make significant impacts toward reducing the carbon footprint of the lifecycle of computers. The ...

USDA-NIFA grant supports microwave tech to zap weed seeds

2024-05-23

By John Lovett

University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. — It’s not just for burritos and popcorn. Microwave technology is also being tested as a new tool to destroy weed seeds and decrease herbicide use.

Scientists and engineers with the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station are investigating the use of 915 MHz microwaves to neutralize a variety of weed seeds underground. The study is supported by a nearly $300,000 Agriculture and Food Research Initiative grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, with additional support ...

Research spotlight: AI enabled body composition analysis predicts outcomes for patients with lung cancer treated with immunotherapy

2024-05-23

Tafadzwa Chaunzwa, MD, a researcher in the Artificial Intelligence in Medicine (AIM) Program at Mass General Brigham and a senior resident physician at the Harvard Radiation Oncology Program, is the lead author of a paper published in JAMA Oncology. Chaunzwa and senior author Hugo Aerts, PhD, director of the AIM Program, and associate professor at Harvard University, shared highlights from their paper.

How would you summarize your study for a lay audience?

As treatments like immunotherapy improve cancer survival rates, there is a growing need for clinical decision-support tools that predict treatment response ...

Silky shark makes record breaking migration

2024-05-23

In a recent study, researchers from the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF), in collaboration with the Guy Harvey Research Institute (GHRI) and Save Our Seas Foundation Shark Research Center (SOSF-SRC) at Nova Southeastern University in Florida, and the Galapagos National Park Directorate (GNPD) have documented the most extensive migration ever recorded for a silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis), revealing critical insights into the behavior of this severely overfished species and emphasizing the urgent need for cooperative international management measures to prevent further population declines.

The ...

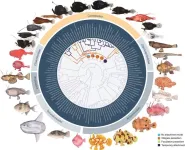

Sexual parasitism helped anglerfish invade the deep sea during a time of global warming

2024-05-23

Members of the vertebrate group including anglerfishes are unique in possessing a characteristic known as sexual parasitism, in which males temporarily attach or permanently fuse with females to mate. Now, researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on May 23 show that sexual parasitism arose during a time of major global warming and rapid transition for anglerfishes from the ocean floor to the deep, open sea.

The findings have implications for understanding evolution and the effects that global warming may have in the deep sea, according to the researchers.

“Our results show how the ...

Archaeology: Differences in Neanderthal and Palaeolithic human childhood stress

2024-05-23

Neanderthal children (who lived between 400,000 and 40,000 years ago) and modern human children living during the Upper Palaeolithic era (between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago) may have faced similar levels of childhood stress but at different developmental stages, according to a study published in Scientific Reports. The authors suggest that these findings could reflect differences in childcare and other behavioural strategies between the two species.

Laura Limmer, Sireen El Zaatari and colleagues analysed the dental enamel of 423 Neanderthal teeth (from 74 Homo neanderthalensis individuals) and 444 Upper Palaeolithic humans (from 102 Homo sapiens ...