(Press-News.org) HOUSTON – (May 23, 2024) – Lighting a gas grill, getting an ultrasound, using an ultrasonic toothbrush ⎯ these actions involve the use of materials that can translate an electric voltage into a change in shape and vice versa.

Known as piezoelectricity, the ability to trade between mechanical stress and electric charge can be harnessed widely in capacitors, actuators, transducers and sensors like accelerometers and gyroscopes for next-generation electronics. However, integrating these materials into miniaturized systems has been difficult due to the tendency of electromechanically active materials to ⎯ at the submicrometer scale, when the thickness is just a few millionths of an inch ⎯ get “clamped” down by the material they are attached to, which significantly dials down their performance.

Rice University researchers and collaborators at the University of California, Berkeley have found that a class of electromechanically active materials called antiferroelectrics may hold the key to overcoming performance limitations due to clamping in miniaturized electromechanical systems. A new study published in Nature Materials reports that a model antiferroelectric system, lead zirconate (PbZrO3), produces an electromechanical response that can be up to five times greater than that of conventional piezoelectric materials even in films that are only 100 nanometers (or 4 millionths of an inch) thick.

“We’ve been using piezoelectric materials for decades,” said Rice materials scientist Lane Martin, who is the corresponding author on the study. “Recently there has been a strong motivation to further integrate these materials into new types of devices that are very small ⎯ as you would want to do for, say, a microchip that goes inside your phone or computer. The problem is that these materials are typically just less usable at these small scales.”

According to current industry standards, a material is considered to have very good electromechanical performance if it can undergo a 1% change in shape ⎯ or strain ⎯ in response to an electric field. For an object that measures 100 inches in length, for instance, getting 1 inch longer or shorter represents 1% strain.

“From a materials science perspective, this is a significant response, since most hard materials can only change by a fraction of a percent,” said Martin, the Robert A. Welch Professor, professor of materials science and nanoengineering and director of the Rice Advanced Materials Institute.

When conventional piezoelectric materials are scaled down to systems less than a micrometer (1,000 nanometers) in size, their performance generally deteriorates significantly due to the interference of the substrate, which dampens their ability to change shape in response to electric field or, conversely, to generate voltage in response to a change in shape.

According to Martin, if electromechanical performance were rated on a scale of 1-10 ⎯ where 1 is lowest performance and 10 is the industry standard of 1% strain ⎯ then clamping is typically expected to bring conventional piezoelectrics’ electromechanical response down from a 10 to the 1-4 range.

“To understand how clamping impacts motion, first picture being in a middle seat on an airplane with no one on either side of you ⎯ you’d be free to adjust your position if you get uncomfortable, overheated, etc.,” Martin said. “Now picture the same scenario, except now you’re seated between two huge offensive linemen from Rice’s football team. You’d be ‘clamped’ between them such that you really couldn’t meaningfully adjust your position in response to a stimulus.”

The researchers wanted to understand how very thin films of antiferroelectrics ⎯ a class of materials that remained understudied until recently due to a lack of access to “model” versions of the materials and to their complex structure and properties ⎯ changed their shape in response to voltage and whether they were likewise susceptible to clamping.

First, they grew thin films of the model antiferroelectric material PbZrO 3 with very careful control of the material thickness, quality and orientation. Next, they performed an array of electrical and electromechanical measurements to quantify the responses of the thin films to applied electric voltage.

“We found the response was considerably larger in the thin films of antiferroelectric material than what is achieved in similar geometries of traditional materials,” said Hao Pan, a postdoctoral researcher in Martin’s research group and lead author on the study.

Measuring shape change at such small scales was not an easy feat. In fact, optimizing the measurement setup required so much labor the researchers documented the process in a separate publication.

“With the perfected measurement setup, we can get a resolution of two picometers ⎯ that’s about a thousandth of a nanometer,” Pan said. “But just showing that a shape change happened doesn’t mean we understand what’s going on, so we had to explain it. This was one of the first studies to reveal the mechanisms behind this high performance.”

With support from their collaborators at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the researchers used a state-of-the-art transmission electron microscope to observe the nanoscale material shapeshift with atomic resolution in real time.

“In other words, we watched the electromechanical actuation as it was happening, so we could see the mechanism for the large shape changes,” Martin said. “What we found was that there is an electric voltage-induced change in the crystal structure of the material, which is like the fundamental building unit or single type of Lego block from which the material is built. In this case, that Lego block gets reversibly stretched with applied electric voltage, giving us a big electromechanical response.”

Surprisingly, the researchers found that not only does clamping not interfere with material performance, but it in fact enhances it. Together with collaborators at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Dartmouth College, they recreated the material computationally in order to get another view of how the clamping affects the actuation under applied electric voltage.

“Our results are the culmination of years of work on related materials, including the development of new techniques to probe them,” Martin said. “By figuring out how to make these thin materials work better, we’re hoping to enable the development of smaller and more powerful electromechanical devices or microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) ⎯ and even nanoelectromechanical systems (NEMS) ⎯ that use less energy and can do things we never thought possible before.”

The research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DE-AC02-05-CH11231, DE-SC-0012375), the Army/ARL (W911NF-19-2-0119), the Army Research Office (W911NF-21-1-0118, W911NF-21-1-0126), the SRC-JUMP ASCENT center, the Department of Defense (FA9550-18-1-0480), the National Science Foundation (1752814) and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center. The content of this press release is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding organizations.

-30-

This news release can be found online at news.rice.edu.

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews.

Peer-reviewed paper:

Clamping enables enhanced electromechanical responses in antiferroelectric thin films | Nature Materials | DOI: 10.1038/s41563-024-01907-y

Authors: Hao Pan, Menglin Zhu, Ella Banyas, Louis Alaerts, Megha Acharya, Hongrui Zhang, Jiyeob Kim, Xianzhe Chen, Xiaoxi Huang, Michael Xu, Isaac Harris, Zischen Tian, Francesco Ricci, Brendan Hanrahan, Jonathan E. Spanier, Geoffroy Hautier, James LeBeau, Jeffrey Neaton and Lane Martin

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41563-024-01907-y

Image downloads:

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2024/05/schematic.jpg

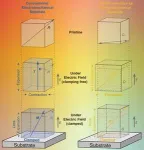

CAPTION: Performance of conventional electromechanical materials versus antiferroelectrics. (Schematic courtesy of Hao Pan)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2024/05/Martin.jpg

CAPTION: Lane Martin is Rice University’s Robert A. Welch Professor, professor of materials science and nanoengineering and director of the Rice Advanced Materials Institute.

(Photo by Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

About Rice:

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation’s top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of architecture, business, continuing studies, engineering, humanities, music, natural sciences and social sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 4,574 undergraduates and 3,982 graduate students, Rice’s undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction, No. 2 for best-run colleges and No. 12 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger’s Personal Finance.

END

Electromechanical material doesn’t get ‘clamped’ down

Rice study identifies high-performance alternative to conventional ferroelectrics

2024-05-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Most young women treated for breast cancer can have children, study shows

2024-05-23

In a study of nearly 200 young women who have survived breast cancer, most of those who tried to conceive were able to become pregnant and give birth

This study fills in major gaps from previous studies of fertility among breast cancer survivors

BOSTON – New research by Dana-Farber Cancer Institute investigators has encouraging news for young women who have survived breast cancer and want to have children.

The study, which tracked nearly 200 young women treated for breast cancer, found that the majority of those who tried to conceive during a median of 11 years after treatment were able to become pregnant and give birth to a child.

The findings, ...

SWOG researchers will present key results at ASCO 2024

2024-05-23

Researchers from SWOG Cancer Research Network, a cancer clinical trials group funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), will share results of their work in 30 presentations at the 2024 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, which takes place May 31 – June 4 in Chicago.

The clinical trials reported on in this work are led by SWOG and conducted by the NIH-funded NCI National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) and the NCI Community Oncology Research ...

MD Anderson Research Highlights: ASCO 2024 Special Edition

2024-05-23

ABSTRACTS: 2018, 2517, 3513, 5504, 6016, 7007, 9515, 12017, LBA8007, LBA9516

CHICAGO ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Research Highlights showcases the latest breakthroughs in cancer care, research and prevention. These advances are made possible through seamless collaboration between MD Anderson’s world-leading clinicians and scientists, bringing discoveries from the lab to the clinic and back.

This special edition features presentations by MD Anderson researchers at the 2024 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting. In addition to the ...

Dae Hyun Kim, MD, ScD, receives 2024 Harvard Medical School Mentoring Award

2024-05-23

Dae Hyun Kim, MD, ScD is the recipient of a 2024 A. Clifford Barger Excellence in Mentoring Award at Harvard Medical School.

Kim is an associate scientist at the Hinda and Arthur Marcus Institute for Aging Research at Hebrew SeniorLife, an HMS Associate Professor of Medicine, a geriatrician at the Division of Gerontology in the Department of Medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and a Harvard School of Public Health Instructor in the Department of Epidemiology.

The Excellence in Mentoring Awards were established to recognize the value of quality mentoring ...

A new study reveals key role of plant-bacteria communication for the assembly of a healthy plant microbiome supporting sustainable plant nutrition

2024-05-23

The results in Nature Communications find that symbiotic, nitrogen-fixing bacteria can ensure dominance among soil microbes due to its signalling-based communication with the legume plant host. Researchers discovered that when legumes need nitrogen, they will send out from the roots and into the soil specific molecules that are in turn recognized by the symbiotic bacteria to produce another molecule, the Nod factor which is recognized back by the legume plant. When this mutual recognition was established, the plant will modify the panel of root secreted molecules and by this will affect which soil bacteria can grow in the vicinity ...

Colleen Ryan named Tufts University's Vice Provost for Faculty

2024-05-23

Colleen Ryan, associate vice provost in the Office of the Vice Provost for Faculty & Academic Affairs Indiana University Bloomington (IUB), has been named vice provost for faculty at Tufts University. She will start in the position on July 1.

Ryan currently holds the rank of professor of Italian in the Department of French and Italian at IUB, is an affiliate faculty member in the Department of Gender Studies, and was the director of undergraduate studies for Italian from 2015-2023. Her areas of expertise ...

Scientists map networks regulating gene function in the human brain

2024-05-23

A consortium of researchers has produced the largest and most advanced multidimensional maps of gene regulation networks in the brains of people with and without mental disorders. These maps detail the many regulatory elements that coordinate the brain’s biological pathways and cellular functions. The research, supported the National Institutes of Health (NIH), used postmortem brain tissue from over 2,500 donors to map gene regulation networks across different stages of brain development and multiple ...

Does it matter if your kids listen to you? When adolescents reject mom’s advice, it still helps them cope

2024-05-23

URBANA, Ill. – Parents are often eager to give their adolescent children advice about school problems, but they may find that youth are less than receptive to their words of wisdom. However, kids who don’t seem to listen to their parents may still benefit from their input, a new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign shows.

The researchers looked at conversations between fifth-grade students and their mothers about academic problems, identifying mom’s advice strategies and the youth’s response. Then they correlated these findings with how ...

Parents of the year: Scavenging raptors lead a collaborative home

2024-05-23

News Release

Journal of Raptor Research

For immediate release

Contact: [Zoey T. Greenberg]

science.writer@raptorresearchfoundation.com

360.739.7170

Parents of the Year: Scavenging Raptors Lead a Collaborative Home Life

Let’s face it, scavengers have a bad reputation. However, according to a new paper published in the Journal of Raptor Research, pairs of scavenging falcons called Chimango Caracaras (Milvago chimango) demonstrate an endearing level of collaboration while raising their chicks. In their paper, “Biparental Care in a Generalist Raptor, the Chimango Caracara in Central Argentina” Diego Gallego-García from ...

Latest from PsychENCODE: A cell-by-cell look at neuropsychiatric diseases

2024-05-23

Deciphering the genetic causes of common neurodevelopmental conditions like autism and common mental illnesses like bipolar disorder has been challenging – not least because of the size and complexity of the human brain – but a new package of research from a global group makes notable progress. Across Science, Science Translational Medicine, and Science Advances, more than a dozen reports from the PsychENCODE Consortium – established in 2015, and dedicated to illuminating the molecular ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Invisible battery parts finally seen with pioneering technique

Tropical forests generate rainfall worth billions, study finds

A yeast enzyme helps human cells overcome mitochondrial defects

Bacteria frozen in ancient underground ice cave found to be resistant against 10 modern antibiotics

Rhododendron-derived drugs now made by bacteria

Admissions for child maltreatment decreased during first phase of COVID-19 pandemic, but ICU admissions increased later

Power in motion: transforming energy harvesting with gyroscopes

Ketamine high NOT related to treatment success for people with alcohol problems, study finds

1 in 6 Medicare beneficiaries depend on telehealth for key medical care

Maps can encourage home radon testing in the right settings

Exploring the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline

Machine learning tool can predict serious transplant complications months earlier

Prevalence of over-the-counter and prescription medication use in the US

US child mental health care need, unmet needs, and difficulty accessing services

Incidental rotator cuff abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging

Sensing local fibers in pancreatic tumors, cancer cells ‘choose’ to either grow or tolerate treatment

Barriers to mental health care leave many children behind, new data cautions

Cancer and inflammation: immunologic interplay, translational advances, and clinical strategies

Bioactive polyphenolic compounds and in vitro anti-degenerative property-based pharmacological propensities of some promising germplasms of Amaranthus hypochondriacus L.

AI-powered companionship: PolyU interfaculty scholar harnesses music and empathetic speech in robots to combat loneliness

Antarctica sits above Earth’s strongest “gravity hole.” Now we know how it got that way

Haircare products made with botanicals protects strands, adds shine

Enhanced pulmonary nodule detection and classification using artificial intelligence on LIDC-IDRI data

Using NBA, study finds that pay differences among top performers can erode cooperation

Korea University, Stanford University, and IESGA launch Water Sustainability Index to combat ESG greenwashing

Molecular glue discovery: large scale instead of lucky strike

Insulin resistance predictor highlights cancer connection

Explaining next-generation solar cells

Slippery ions create a smoother path to blue energy

Magnetic resonance imaging opens the door to better treatments for underdiagnosed atypical Parkinsonisms

[Press-News.org] Electromechanical material doesn’t get ‘clamped’ downRice study identifies high-performance alternative to conventional ferroelectrics