(Press-News.org) JUNE 3, 2024, NEW YORK – A novel immunotherapy approach developed by Ludwig Cancer Research scientists employs a two-pronged attack against solid tumors to boost the immune system’s ability to target and eliminate cancer cells.

The research focuses on an immunotherapy called adoptive cell transfer (ACT), which involves extracting T cells from a patient, enhancing their ability to fight cancer, expanding them in culture and reinfusing them into the patient’s body.

“While T cell therapies have shown tremendous success in treating certain blood cancers, solid tumors present a more complex challenge due to immune-suppressive mechanisms at play in the tumor microenvironment,” said Ludwig Lausanne’s Melita Irving, who led the study. “T cells alone may not be sufficient, which is why we're exploring ways to boost their effectiveness by integrating other immune-enhancing strategies.”

In a new study, detailed in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, Irving and her team modified T cells to secrete CV1, a high-affinity version of the human signal regulatory protein alpha (SiRPα).

SiRPα normally interacts with CD47, a protein found on the surface of healthy cells that transmits a "don't eat me" signal to prevent macrophages from gobbling them up. However, many cancer cells exploit this system by overexpressing CD47 to avoid being eaten, or “phagocytized.”

"The innate immune system, especially macrophages—which can consume tumor cells—is crucial to our immune defenses against cancer,” Irving explained. (T cells belong to a separate arm of the immune system known as the adaptive immune system.)

The previously developed CV1 decoy utilized by Irving’s team binds CD47 with high affinity, effectively silencing the "don't eat me" signal. This, it was expected, would make the cancer cells more recognizable and susceptible to macrophage attack while they were simultaneously being targeted by the engineered T cells, which had also been co-engineered to express an affinity-optimized T cell receptor (TCR).

However, the team encountered an unexpected problem. The CV1 their T cells were engineered to secrete included an Fc tail, which is ordinarily found at the tail end of an antibody molecule and doubles as a tag that draws macrophage attack. Since that tag now coated the T cells secreting the engineered CV1, it invited a full-on macrophage assault on the therapeutic T cells, leading to their depletion in treated mice.

To correct this, Evangelos Stefanidis, first author of the study and a recent PhD graduate from Irving’s group, modified the T cells to express CV1 alone, without the Fc tail. This prevented the engineered T cells from being targeted by human macrophages.

Moreover, combining these CV1-producing T cells with cancer-targeting antibodies such as Avelumab and Cetuximab further improved the ability of macrophages to consume tumor cells. This was because these antibodies—which target the immune-suppressing PD-L1 molecule and the growth-promoting Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), respectively—possess active Fc tails that engage macrophages to attack the tumor cells specifically. The team also observed that treating mice with these antibodies favorably altered the tumor microenvironment to support immune attack.

“By removing the Fc tail, we could spare the T cells from human macrophages, and by combining the co-engineered T cells with clinical antibodies comprising an active Fc tail, we specifically augmented phagocytosis of the tumor cells by macrophages,” Irving explained.

The findings could also help explain why clinical trials of the antibody drug magrolimab have faced significant challenges, including poor patient responses and infections. Like the CV1 decoy, magrolimab blocks the CD47 “don’t eat me” signal on tumor cells to encourage their destruction by the immune system. But if—like the CV1 decoys with Fc tails—its blocking action is not targeted exclusively to cancer cells, it could provoke the destruction of healthy tissues.

“It is possible that magrolimab is also targeting immune cells, including T cells, for phagocytosis,” Irving said. “Our combination treatment strategy helps direct phagocytosis specifically against tumor cells while sparing our engineered T cells. Our findings also highlight the complexities of cancer treatment and the importance of a nuanced approach to immunotherapy."

This study was supported by Ludwig Cancer and the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Melita Irving leads the T cell engineering group in Ludwig Lausanne’s Human integrated tumor immunology discovery engine (Hi-TIDe).

# # #

About Ludwig Cancer Research

Ludwig Cancer Research is an international collaborative network of acclaimed scientists that has pioneered cancer research and landmark discovery for more than 50 years. Ludwig combines basic science with the translation and clinical evaluation of its discoveries to accelerate the development of new cancer diagnostics, therapies and prevention strategies. Since 1971, Ludwig has invested nearly $3 billion in life-changing science through the not-for-profit Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research and the six U.S.-based Ludwig Centers. To learn more, visit www.ludwigcancerresearch.org.

For additional information please contact communications@ludwigcancerresearch.org.

END

As they seep and calve into the sea, melting glaciers and ice sheets are raising global water levels at unprecedented rates. To predict and prepare for future sea-level rise, scientists need a better understanding of how fast glaciers melt and what influences their flow.

Now, a study by MIT scientists offers a new picture of glacier flow, based on microscopic deformation in the ice. The results show that a glacier’s flow depends strongly on how microscopic defects move through the ice.

The researchers found they could estimate ...

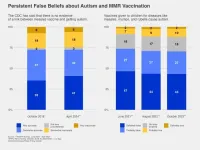

As measles cases rise across the United States and vaccination rates for the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine continue to fall, a new survey finds that a quarter of U.S. adults do not know that claims that the MMR vaccine causes autism are false.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has said there is no evidence linking the measles vaccine and getting autism. But 24% of U.S. adults do not accept that – they say that statement is somewhat or very inaccurate – and another 3% are not sure, according to the survey by the Annenberg Public Policy Center (APPC) of the University of Pennsylvania. About three-quarters of those surveyed ...

BOSTON—The type of weight loss surgery women undergo before becoming pregnant may affect how much weight their children gain in the first three years of life, suggests a study being presented Monday at ENDO 2024, the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Boston, Mass.

Researchers found children born to women who underwent the bariatric procedure known as sleeve gastrectomy before they became pregnant gain more weight per month on average in the first three years of life compared with children born to women who had the less common ...

BOSTON—Patients with Cushing’s syndrome who are recovering from surgery and wear a headband that tracks brain activity while they meditate may have less pain and better physical functioning compared with patients not using the device, suggests a study being presented Monday at ENDO 2024, the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Boston, Mass.

The headband, called MUSE-2, uses electroencephalogram (EEG) sensors to measure brain activity and provides audio biofeedback while a person meditates.

Cushing's syndrome is a rare ...

BOSTON—Exposure to some endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) that harm the thyroid gland has increased over the past 20 years among U.S. women of childbearing age and pregnant women, especially among those with lower social and economic status, a new study finds. The results will be presented Monday at ENDO 2024, the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Boston, Mass.

“Our research underscores the importance of addressing socioeconomic disparities in EDC exposure among women of reproductive age and pregnant women to mitigate potential adverse effects on thyroid health,” ...

BOSTON—Some women who experience menopause early—before age 40—have an increased risk for developing breast and ovarian cancer, according to research being presented Monday at ENDO 2024, the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting in Boston, Mass.

“There is also higher risk of breast, prostate and colon cancer in relatives of these women,” said Corrine Welt, M.D., chief of the Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes at the University of Utah Health in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Welt and colleagues began the study with the hypothesis that some women with primary ovarian insufficiency and their family members might ...

A new series published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology highlights how pollution, in all its forms, is a greater health threat than that of war, terrorism, malaria, HIV, tuberculosis, drugs and alcohol combined.

The researchers from the University of Edinburgh, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Global Observatory on Planetary Health Boston College, Centre Scientifique de Monaco, University Medical Centre Mainz, and the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute focus on global warming, air pollution and exposure to wildfire smoke, and highlight the lesser-known drivers of heart disease including soil, noise and light pollution, and exposure to toxic chemicals.

They ...

The University of Cincinnati’s Jack Davis, Carl W. Blegen Professor of Greek archaeology in the Department of Classics, has been elected to the prestigious American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

With this honor, Davis joins the ranks of luminaries such as former U.S. President John Adams (elected in 1780), language scholar Noah Webster (of dictionary fame, tapped in 1799), and more currently playwright Lin-Manuel Miranda, and actor and philanthropist George Clooney.

Begun just four years after the Declaration of Independence ...

Five global science and technology projects have been selected to join the Ocean Biogeochemistry Virtual Institute (OBVI) addressing gaps in ocean data and modeling efforts by improving the breadth of research in the field and expanding capacity to understand ocean resources. Schmidt Sciences, started by Eric and Wendy Schmidt, will bring together 60 scientists from 11 countries. The research will provide clarity on how much carbon dioxide the ocean can hold and the resilience of marine ecosystems in a rapidly warming world.

OBVI, through a joint call for ...

Physician-scientists from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Marnix E. Heersink School of Medicine led a nationwide study to examine the role of carpal tunnel syndrome in predicting the risk of cardiac amyloidosis.

In their study published in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings, UAB researchers collaborated with researchers from Weill Cornell Medicine and Columbia University to show that carpal tunnel syndrome preceded the development of cardiac amyloidosis by 10-15 years and individuals with carpal tunnel syndrome were at a high risk of developing cardiac amyloidosis.

“Cardiac amyloidosis is an underdiagnosed ...