(Press-News.org) CHAPEL HILL, North Carolina – Researchers at UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and colleagues have established the most comprehensive molecular portrait of the workings of KRAS, a key cancer-causing gene or "oncogene," and how its activities impact pancreatic cancer outcomes. Their findings could help to better inform treatment options for pancreatic cancer, which is the third leading cause of all cancer deaths in the United States.

The research was published as two separate articles in Science.

“Because less than 40% of pancreatic cancers respond to treatment with KRAS inhibitors, if we can establish molecular markers to predict which patients will respond, we can better provide them with specific treatments, which should improve their outcomes,” said UNC Lineberger’s Channing J. Der, PhD, Sarah Graham Kenan Distinguished Professor at UNC School of Medicine’s Department of Pharmacology and a corresponding author of both articles. “From diagnosis to death, the average pancreatic cancer patient treated with chemotherapy lives 6 to 12 months, so there’s a very limited time to offer a treatment which will work.”

KRAS is one of the most commonly mutated genes in human cancers and it is found in more than 90% of pancreatic cancer tumors. Exactly how it spurs cancer growth, however, is poorly understood. That’s why UNC Lineberger researchers embarked on their extensive efforts to figure out what other genes and proteins make KRAS expression so lethal.

In the most detailed analysis to date, they demonstrated that the molecular pathway most responsible for the cancer-driving functions of KRAS is highly dependent on a protein called ERK that has dual functions in regulating which genes are expressed and which proteins are active. While ERK has been one of the most intensively studied cancer pathways, and it is well-established that ERK is among the significant players in KRAS function, its relative importance and precisely how ERK carries out its role have been unclear.

Indeed, a core finding of the Science papers was that activation of the ERK protein alone is the key driver of resistance to drugs that inhibit KRAS. Taking advantage of improved methods to study cellular signaling, the researchers demonstrated that the ERK protein regulates the expression of a remarkably complex array of thousands of genes and changes the activity of thousands of proteins. Excitingly, the researchers confirmed that their findings in cancer models could accurately reflect responses in patients treated with ERK and KRAS therapies for their pancreatic, colorectal and lung cancers.

Currently, two KRAS drugs have been approved for cancer treatment, and many more are currently being evaluated in ongoing clinical trials. In related studies, Der and colleagues contributed to two articles published in Nature in April about a promising anti-KRAS drug that is effective against many different KRAS mutations. They found that the MYC oncogene can cause resistance to KRAS therapies. Closing the circle, the new Science papers established that MYC is a significant component of how KRAS and ERK support cancer growth and a driver of resistance to KRAS and ERK therapies.

“Our next steps are elucidating more aspects of basic and foundational research regarding KRAS,” Der said. “We will continue to mine the growing body of scientific knowledge we have developed, with the ultimate goal of helping advance the clinical development of newer and better KRAS inhibitors.”

Authors and disclosures

In addition to Der, Jeffrey A. Klomp, PhD, assistant professor of pharmacology at UNC Lineberger and UNC School of Medicine, was the co-corresponding author of the article “Defining the KRAS- and ERK-dependent transcriptome in KRAS-mutant cancers.” Clint A. Stalnecker, PhD, assistant professor of pharmacology at UNC Lineberger and UNC School of Medicine, was the co-corresponding author of the article “Determining the ERK-regulated phosphoproteome driving KRAS-mutant cancer,” and Jennifer E. Klomp, PhD, a postdoctoral research associate at UNC Lineberger, was first author.

A complete list of authors, their disclosures and funders of support of the research is published in the papers.

END

Researchers at the Ningbo Institute of Materials Technology and Engineering (NIMTE) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in collaboration with research groups from the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China and Fudan University, have developed a fatigue-free ferroelectric material based on sliding ferroelectricity.

The study was published in Science.

Ferroelectric materials have switchable spontaneous polarization that can be reversed by an external electric field, which have been widely applied to non-volatile memory, sensing, and ...

Around 100 million years ago, a remarkable evolutionary shift allowed placental mammals to diversify and conquer many cold regions of our planet. New research from Stockholm University shows that the typical mammalian heater organ, brown fat, evolved exclusively in modern placental mammals.

In collaboration with the Helmholtz Munich and the Natural History Museum Berlin in Germany, and the University of East Anglia in the U.K., the Stockholm research team demonstrated that marsupials, our distant relatives, possess a not fully evolved form of brown fat. They discovered that the pivotal heat-producing protein called ...

The role that Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) plays in the development of multiple sclerosis (MS) may be caused a higher level of cross-reactivity, where the body’s immune system binds to the wrong target, than previously thought.

In a new study published in PLOS Pathogens, researchers looked at blood samples from people with multiple sclerosis, as well as healthy people infected with EBV and people recovering from glandular fever caused by recent EBV infection. The study investigated how the immune system deals with EBV infection as part of worldwide efforts to understand how this common virus can lead to the development of multiple ...

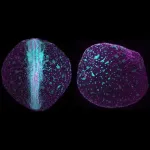

The annual killifish lives in regions with extreme drought. A research group at the University of Basel now reports in “Science” that the early embryogenesis of killifish diverges from that of other species. Unlike other fish, their body structure is not predetermined from the outset. This could enable the species to survive dry periods unscathed.

The turquoise killifish inhabits areas characterized by extreme conditions. The species, native to Africa, can survive prolonged periods of drought ...

Researchers at the University of Michigan and Brown University have developed a new computational method to analyze complex tissue data that could transform our current understanding of diseases and how we treat them.

Integrative and Reference-Informed tissue Segmentation, or IRIS, is a novel machine learning and artificial intelligence method that gives biomedical researchers the ability to view more precise information about tissue development, disease pathology and tumor organization.

The findings are published ...

NEW YORK, NY--An injectable emulsion containing two omega-3 fatty acids found in fish oil markedly reduced brain damage in newborn rodents after a disruption in the flow of oxygen to the brain near birth, a study by researchers at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons has found.

Brain injury due to insufficient oxygen is a severe complication of labor and delivery that occurs in one to three out of every 1,000 live births in the United States. Among babies who survive, the condition can lead to cerebral palsy, cognitive disability, epilepsy, pulmonary hypertension, and neurodevelopmental conditions.

“Hypoxic ...

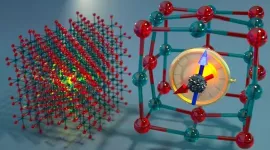

Calcium oxide is a cheap, chalky chemical compound commonly used in the manufacturing of cement, plaster, paper, and steel. But the material may soon have a more high-tech application.

UChicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering researchers and their collaborator in Sweden have used theoretical and computational approaches to discover how tiny, lone atoms of bismuth embedded within solid calcium oxide can act as qubits — the building blocks of quantum computers and quantum communication devices. These qubits are described today in Nature Communications.

“This system has even better properties than we expected,” said Giulia Galli, Liew Family Professor ...

TAMPA, Fla. (June 6, 2024) — In a groundbreaking advance that could revolutionize bladder cancer treatment, a novel combination of cretostimogene grenadenorepvec and pembrolizumab has shown remarkable efficacy in patients with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG)-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Results from the phase 2 CORE-001 trial, published today in Nature Medicine, reveal a significant improvement in complete response rates and long-term disease control, offering new hope for patients with this challenging condition who face limited treatment options.

The trial included patients with BCG-unresponsive carcinoma in situ of the bladder, a condition that is notoriously ...

The molecules that make up the matter around us are in constant motion. What if we could harness that energy and put it to use?

Over 150 years ago Maxwell theorized that if molecules’ motion could be measured accurately, this information could be used to power an engine. Until recently this was a thought experiment, but technological breakthroughs have made it possible to build working information engines in the lab.

With funding from the Foundational Questions Institute, SFU Physics professors John Bechhoefer and David Sivak teamed up to build an information engine and test its limits. Their work has greatly advanced ...

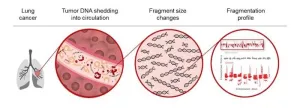

Using artificial intelligence technology to identify patterns of DNA fragments associated with lung cancer, researchers from the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and other institutions have developed and validated a liquid biopsy that may help identify lung cancer earlier.

In a prospective study published June 3 in Cancer Discovery, the team demonstrated that artificial intelligence technology could identify people more likely to have lung cancer based on DNA fragment patterns in the blood. The study enrolled about 1,000 participants with and without cancer who met the criteria for traditional lung ...