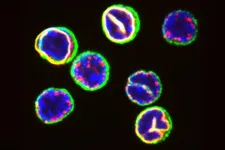

(Press-News.org) From the outside, most T cells look the same: small and spherical. Now, a team of researchers led by Berend Snijder from the Institute of Molecular Systems Biology at ETH Zurich has taken a closer look inside these cells using advanced techniques. Their findings show that the subcellular spatial organisation of cytotoxic T cells – which Snijder refers to as their cellular architecture – has a major influence on their fate.

Characteristics that determine a cell’s fate

When cells with nuclear invaginations encounter a pathogen, they turn into powerful effector cells that rapidly proliferate and kill the pathogen. Their fellow cells with a spherical nucleus – that is, with no nuclear invaginations – evolve at a more leisurely pace: they take longer to activate and eventually differentiate into long-lived memory cells that defend the organism against future attacks by the same pathogen.

Scientists identified these two functionally distinct populations of T cells some 50 years ago. “But until now we weren’t sure which characteristics determined whether a T cell would become an effector cell or a memory cell,” says Ben Hale, a postdoc in Snijder’s research group and lead author of the article that recently appeared in the journal Science.

To help identify these characteristics, the researchers developed a platform that automatically analyses microscopy images of immune cells. They then presented this platform with thousands of T cells from 24 healthy volunteers who donated their blood to the Zurich Blood Donation Service of the Swiss Red Cross.

Unexpected differences

Using a machine-learning approach, the platform classified the cells into three different groups. “We’d already seen how some T cells appear bottle-shaped when activated,” Snijder says. “But we didn’t expect the platform to split the round cells into two different groups.”

On further investigation, the researchers also discovered that the differences in cellular architecture between the two classes of round cells also has a functional significance. “The cells with nuclear invaginations are designed to activate rapidly: many of them convert into bottle-shaped effector cells within 24 hours,” Hale says.

“They also mount a stronger response when activated – and they proliferate much faster than cells without nuclear invaginations,” Snijder adds. He and his team also identified the molecular mechanism that leads to the faster and stronger activation of cells with nuclear invaginations: “Their special cellular architecture enables a heightened influx of calcium ions,” Snijder says.

Both researchers emphasise that there are still many questions to be answered. For example, Snijder and his team now hope to discover how the organism consistently ensures that around 60 percent of cytotoxic T cells in the blood have nuclear invaginations, while 35 percent have no invaginations and the remaining 5 percent are bottle-shaped.

Making therapies more clinically effective

Snijder and Hale note that their results are not only “important for gaining a better understanding of how our immune cells work”, but also play a crucial role in the fight against cancer, for example: “Many novel therapies use T cells to kill cancer cells,” Snijder says. “If we can find a way to specifically select and deploy these cellular architectures, we may be able to improve the clinical efficacy of such therapies.”

END

Researchers identify key differences in inner workings of immune cells

2024-06-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Molecular pathway that impacts pancreatic cancer progression and response to treatment detailed

2024-06-06

CHAPEL HILL, North Carolina – Researchers at UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and colleagues have established the most comprehensive molecular portrait of the workings of KRAS, a key cancer-causing gene or "oncogene," and how its activities impact pancreatic cancer outcomes. Their findings could help to better inform treatment options for pancreatic cancer, which is the third leading cause of all cancer deaths in the United States.

The research was published as two separate articles in Science.

“Because ...

Ferroelectric material is now fatigue-free

2024-06-06

Researchers at the Ningbo Institute of Materials Technology and Engineering (NIMTE) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in collaboration with research groups from the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China and Fudan University, have developed a fatigue-free ferroelectric material based on sliding ferroelectricity.

The study was published in Science.

Ferroelectric materials have switchable spontaneous polarization that can be reversed by an external electric field, which have been widely applied to non-volatile memory, sensing, and ...

Marsupials key to discovering the origin of heater organs in mammals

2024-06-06

Around 100 million years ago, a remarkable evolutionary shift allowed placental mammals to diversify and conquer many cold regions of our planet. New research from Stockholm University shows that the typical mammalian heater organ, brown fat, evolved exclusively in modern placental mammals.

In collaboration with the Helmholtz Munich and the Natural History Museum Berlin in Germany, and the University of East Anglia in the U.K., the Stockholm research team demonstrated that marsupials, our distant relatives, possess a not fully evolved form of brown fat. They discovered that the pivotal heat-producing protein called ...

Epstein-Barr Virus and brain cross-reactivity: possible mechanism for Multiple Sclerosis

2024-06-06

The role that Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) plays in the development of multiple sclerosis (MS) may be caused a higher level of cross-reactivity, where the body’s immune system binds to the wrong target, than previously thought.

In a new study published in PLOS Pathogens, researchers looked at blood samples from people with multiple sclerosis, as well as healthy people infected with EBV and people recovering from glandular fever caused by recent EBV infection. The study investigated how the immune system deals with EBV infection as part of worldwide efforts to understand how this common virus can lead to the development of multiple ...

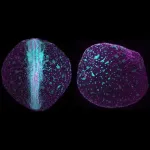

Fish out of water: How killifish embryos adapted their development

2024-06-06

The annual killifish lives in regions with extreme drought. A research group at the University of Basel now reports in “Science” that the early embryogenesis of killifish diverges from that of other species. Unlike other fish, their body structure is not predetermined from the outset. This could enable the species to survive dry periods unscathed.

The turquoise killifish inhabits areas characterized by extreme conditions. The species, native to Africa, can survive prolonged periods of drought ...

Novel AI method could improve tissue, tumor analysis and advance treatment of disease

2024-06-06

Researchers at the University of Michigan and Brown University have developed a new computational method to analyze complex tissue data that could transform our current understanding of diseases and how we treat them.

Integrative and Reference-Informed tissue Segmentation, or IRIS, is a novel machine learning and artificial intelligence method that gives biomedical researchers the ability to view more precise information about tissue development, disease pathology and tumor organization.

The findings are published ...

Omega-3 therapy prevents birth-related brain injury in newborn rodents

2024-06-06

NEW YORK, NY--An injectable emulsion containing two omega-3 fatty acids found in fish oil markedly reduced brain damage in newborn rodents after a disruption in the flow of oxygen to the brain near birth, a study by researchers at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons has found.

Brain injury due to insufficient oxygen is a severe complication of labor and delivery that occurs in one to three out of every 1,000 live births in the United States. Among babies who survive, the condition can lead to cerebral palsy, cognitive disability, epilepsy, pulmonary hypertension, and neurodevelopmental conditions.

“Hypoxic ...

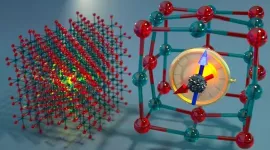

Calcium oxide’s quantum secret: nearly noiseless qubits

2024-06-06

Calcium oxide is a cheap, chalky chemical compound commonly used in the manufacturing of cement, plaster, paper, and steel. But the material may soon have a more high-tech application.

UChicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering researchers and their collaborator in Sweden have used theoretical and computational approaches to discover how tiny, lone atoms of bismuth embedded within solid calcium oxide can act as qubits — the building blocks of quantum computers and quantum communication devices. These qubits are described today in Nature Communications.

“This system has even better properties than we expected,” said Giulia Galli, Liew Family Professor ...

Innovative combination therapy shows promise for bladder cancer patients unresponsive to standard treatment

2024-06-06

TAMPA, Fla. (June 6, 2024) — In a groundbreaking advance that could revolutionize bladder cancer treatment, a novel combination of cretostimogene grenadenorepvec and pembrolizumab has shown remarkable efficacy in patients with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG)-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Results from the phase 2 CORE-001 trial, published today in Nature Medicine, reveal a significant improvement in complete response rates and long-term disease control, offering new hope for patients with this challenging condition who face limited treatment options.

The trial included patients with BCG-unresponsive carcinoma in situ of the bladder, a condition that is notoriously ...

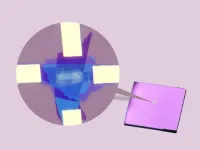

SFU Physics collaboration pushes an information engine to its limits

2024-06-06

The molecules that make up the matter around us are in constant motion. What if we could harness that energy and put it to use?

Over 150 years ago Maxwell theorized that if molecules’ motion could be measured accurately, this information could be used to power an engine. Until recently this was a thought experiment, but technological breakthroughs have made it possible to build working information engines in the lab.

With funding from the Foundational Questions Institute, SFU Physics professors John Bechhoefer and David Sivak teamed up to build an information engine and test its limits. Their work has greatly advanced ...