(Press-News.org) Cambridge scientists have grown ‘mini-guts’ in the lab to help understand Crohn’s disease, showing that ‘switches’ that modify DNA in gut cells play an important role in the disease and how it presents in patients.

The researchers say these mini-guts could in future be used to identify the best treatment for an individual patient, allowing for more precise and personalised treatments.

Crohn’s disease is a form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It is a life-long condition characterised by inflammation of the digestive tract that affects around one in 350 people in the UK, with one in four presenting before the age of 18. Even at its mildest, it can cause symptoms that have a major impact on quality of life including stomach pain, diarrhoea, weight loss and fatigue, but it can also lead to extensive surgery, inpatient admissions, exposure to toxic drugs and have a major impact on patient and their families.

While there is some evidence that an individual is at greater risk of developing the condition if a first-degree relative has Crohn’s, there has been only limited success in identifying genetic risk factors. As a result, it’s estimated that only 10% of inheritance is due to variations in our DNA.

Matthias Zilbauer, Professor of Paediatric Gastroenterology at the University of Cambridge and Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (CUH), said: “The number of cases of Crohn’s disease and IBD are rising dramatically worldwide, particularly amongst younger children, but despite decades of research, no one knows what causes it. Part of the problem is that it’s been difficult to model the disease. We’ve had to rely mainly on studies in mice, but these are limited in what they can tell us about the disease in people.”

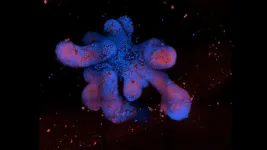

In research published today in Gut, Professor Zilbauer and colleagues used cells from inflamed guts, donated by 160 patients, mainly patients and adolescents, at CUH to grow more than 300 mini-guts – known as organoids – in the lab to help them better understand the condition. Samples were donated by patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, as well as by patients unaffected by IBD.

“The organoids that we've generated are primarily from children and adolescents,” said Professor Zilbauer. “They’ve essentially given us pieces of their bowel to help with our research. Crohn’s can be a severe condition to have to deal with at any age, but without our volunteers’ bravery and support, we would not be able to make such discoveries as this.”

Organoids are 3D cell cultures that mimic key functions of a particular organ, in this case the epithelium – the lining of the gut. The researchers grew them from specific cells, known as stem cells, taken from the gut. Stem cells live forever in the gut, constantly dividing allowing the gut epithelium to regenerate.

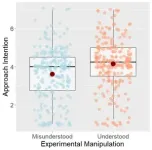

Using these organoids, they showed that the epithelia in the guts of Crohn’s disease patients have different ‘epigenetic’ patterns on their DNA compared to those from healthy controls. Epigenetics is where our DNA is modified by ‘switches’ attached to our DNA that turn genes on and off – or turn their activity up or down – leaving the DNA itself intact, but changing the way a cell functions.

Professor Zilbauer, a researcher at the Stem Cell Institute at the University of Cambridge, said: “What we saw was that not only were the epigenetic changes different in Crohn’s disease, but there was a correlation between these changes and the severity of the disease. Every patient’s disease course is different, and these changes help explain why – not every organoid had the same epigenetic changes.”

The researchers say the organoids could be used to develop and test new treatments, to see how effective they are on the lining of the gut in Crohn’s disease. It also opens up the possibility of tailoring treatments to individual patients.

Co-author Dr Robert Heuschkel, Consultant Paediatric Gastroenterologist at CUH and Lead of the Paediatric IBD Service, said: “At the moment, we have no way of knowing which treatment will work best for a patient. Even those treatments we currently have only work in around half of our patients and become less effective over time. It's a huge problem.

“In future, you could imagine taking cells from a particular patient, growing their organoid, testing different drugs on the organoid, and saying, ‘OK, this is the drug that works for this person’.”

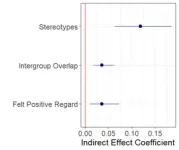

The research highlighted a specific pathway implicated in Crohn’s, known as major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-I. This pathway allows immune cells to recognise antigens – that is, a toxin or other foreign substance that induces an immune response in the body, and which could include molecules in our food, or our gut microbiota. The team showed that the cells forming the inner lining of the gut in Crohn’s disease patients have an increased activity of MHC-I, which can lead to inflammation in specific parts of the gut.

“This is the first time where anyone has been able to show that stable epigenetic changes can explain what is wrong in the gut epithelium in patients with Crohn's disease,” said Professor Zilbauer.

The epigenetic modifications were found to be very stable, which may explain why even after treatment, when a patient appears to be healed, their inflammation can return after several months – the drugs are treating the symptoms, not the underlying cause.

Epigenetic changes are programmed into our cells very early on during the development of the baby in the womb. They are influenced by environmental factors, which may include exposure to infections or antibiotics – or even lack of exposure to infection, the so-called ‘hygiene hypothesis’ that says we are not exposed to sufficient microbes for our immune systems to properly develop. The researchers say this may offer one possible explanation for how the epigenetic changes that lead to Crohn’s disease occur in the first place.

The research was largely supported by the Medical Research Council. It was also supported through collaboration with the Milner Therapeutics Institute, University of Cambridge.

Cambridge Enterprise is working with Professor Zilbauer and team and has recently filed a patent for this technology. They are seeking commercial partners to help with the development of this opportunity.

Arthur’s story: “It's quite cool to be part of the study”

Arthur Hatt has just returned from school. It’s been a particularly fun day today as rehearsals are underway for his school play, Aladdin – and he has one of its most important parts, the Genie.

Although Arthur is back at school full time now, there have been long periods where he was only able to manage half days. “I’d go in for the morning and then come home and just go to bed and sleep or read in bed,” he says.

The reason is that Arthur has Crohn’s disease, a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Now aged 11, he was diagnosed with the condition aged nine – but his mother Sian says that in hindsight, he was showing symptoms from a very early age.

“From the age of about 12 to 18 months, he was having problems with his tummy – loose stools all the time and lots of stomach pains,” she says.

Getting a diagnosis was not straightforward. There was no family history of inflammatory bowel disease or Crohn's disease, so no one thought to consider this option. (Since then, however, Arthur’s older brother has also been diagnosed with the condition.)

“We were told he had toddler diarrhoea, which is common and he’d probably grow out of,” Sian says. “Then they said try eliminating dairy from his diet as it could be an intolerance. Then they said, oh, well, now try and eliminate gluten. When he was five or six, we got a referral to our local hospital who diagnosed him with abdominal migraines.”

Eventually, Arthur was seen by a doctor who recognised the signs of IBD and gave him a simple test known as a faecal calprotectin test, which looks for unusually high levels of the protein calprotectin in the stools – a sign of inflammation. By this time, he was experiencing a lot of pain, as well as blood in his stools.

Following the test, he was referred to Addenbrooke’s Hospital, where he was seen by Professor Matthias Zilbauer.

“That was the first time really that we felt like, OK, somebody knows what's happening and there are things that they can do,” says Sian.

Arthur was prescribed the drug azathioprine, which he is still on to this day. Because it can take time for the effects of the medication to work, he was also temporarily prescribed steroids. “They made me feel jittery,” he says, “and I was really, really hungry.”

Azathioprine by itself has not been enough to fully control his symptoms, so he has had to try several other medications. He is also receiving infliximab, which is given via infusion at Addenbrooke’s.

“The first indications seem to be quite promising,” says Sian. “Even after the first dose, there seems to have been an improvement.”

The drugs do, however, come with side-effects. Azathioprine, for example, can make the skin more sensitive to light, so Arthur has to wear sunscreen whenever he goes outside. The treatments also tend to suppress the immune system, leaving him more susceptible to infections.

“Autumn has been tricky in the past, because it's cough and cold and virus season at school,” Sian says, “Arthur tends to pick up every one of them, and it's tiring for him when that happens.”

The family have learned to pace themselves, working out through trial and error how much Arthur is able to do without tiring himself out.

“School holidays now are a lot more about resting than they are about busy days,” Sian says. “We try and keep things quite chilled. He's so good at pushing through and doing things. He likes to be a busy bee, but we found that if he pushes through too much, he can then cause himself more trouble in the long run.”

Fortunately, Arthur still manages to do the things he enjoys. He enjoys performing – hence his starring role in Aladdin. “I really like dancing, especially Latin and street dance,” he says. “I manage to do most of the things I like, but I get tired sometimes.”

Arthur is one of the children taking part in the Translational Research in Intestinal Physiology and Pathology (TRIPP) study at the University of Cambridge, which is aimed at understanding our gut health. He has donated some of the cells from his intestine, which Professor Zilbauer are colleagues are now using to grow ‘mini-guts’ to better understand Crohn’s disease. Arthur and his family have met the scientists at a family day at the hospital aimed at showing the children how they’re helping research.

“I think it's quite cool to be part of the study,” he says. “It’s nice to know they're trying to get more information about Crohn’s.”

Sian adds: “The real hope is that eventually, we’ll be able to take away a lot of the trial and error with what works and what doesn't work – because it’s different for every patient. That would be amazing.”

These days, more and more children are being diagnosed with Crohn’s disease and IBD. To these children, Arthur has a message: “There are bad days and there are good days, but eventually you'll find the right medicine. Sometimes it can take a really long time, but eventually they’ll find the thing that works for you.”

For now, though, he’s just looking forward to getting on stage and working his genie magic on the audience.

Reference

Dennison, T et al. Patient-derived organoid biobank identifies epigenetic dysregulation of intestinal epithelial MHC-I as a novel mechanism in severe Crohn’s disease. Gut; 11 Jun 2024; 10.1136/gutjnl-2024-332043

END

Lab-grown ‘mini-guts’ could help in development of new and more personalized treatments for Crohn’s disease

Epigenetic changes to DNA help explain differences in disease severity in patients

2024-06-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How the brain is affected by Huntington’s Disease

2024-06-11

The genetic disease Huntington’s not only affects nerve cells in the brain but also has widespread effects on microscopic blood vessels according to research.

These changes to the vasculature were also observed in the pre-symptomatic stages of the disease, demonstrating the potential for this research for predicting brain health and evaluating the beneficial effects of lifestyle changes or treatments.

Huntington’s disease is an inherited genetic condition leading to dementia, with a progressive decline in a person’s movement, memory, and cognition. There is currently no ...

MOLLER experiment baselined and moving forward

2024-06-11

NEWPORT NEWS – The U.S. Department of Energy’s Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility is moving forward on a project to gain new insight into the interactions of electrons. The MOLLER experiment will make an extremely precise measurement of the electron’s force field to learn about specific and rare interactions with other subatomic particles. On May 28, the experiment received approvals of both Critical Decision 2 and Critical Decision 3 from the DOE.

The MOLLER research program was established at Jefferson Lab as a DOE Major Item of Equipment (MIE) project to build the equipment required to support the experiment.

These ...

Engaging with patients for better treatments and outcomes for smell and taste disorders

2024-06-11

PHILADELPHIA (June 10, 2024) – Researchers and patient advocates from the Monell Chemical Senses Center, Smell and Taste Association of North America (STANA), and Thomas Jefferson University came together during the COVID-19 pandemic to incorporate patient voices in efforts to prioritize research areas focused on improving care for people with smell and taste disorders.

To this end, in 2022 these collaborators conducted a survey and listening sessions with patients, caregivers, and family members affected by impaired smell or taste. They asked about their individual perceptions of the effectiveness of treatments, among other topics. Using an online questionnaire, ...

Study shows first evidence of sex differences in how pain can be produced

2024-06-10

Research suggests that males and females differ in their experience of pain, but up until now, no one knew why. In a recent study published in BRAIN, University of Arizona Health Sciences researchers became the first to identify functional sex differences in nociceptors, the specialized nerve cells that produce pain.

The findings support the implementation of a precision medicine-based approach that considers patient sex as fundamental to the choice of treatment for managing pain.

“Conceptually, this paper is a big advance in our ...

Hubble finds surprises around a star that erupted 40 years ago

2024-06-10

Astronomers have used new data from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and the retired SOFIA (Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy) as well as archival data from other missions to revisit one of the strangest binary star systems in our galaxy – 40 years after it burst onto the scene as a bright and long-lived nova. A nova is a star that suddenly increases its brightness tremendously and then fades away to its former obscurity, usually in a few months or years.

Between April and September 1975, the binary system HM Sagittae (HM Sge) grew 250 times brighter. Even more unusual, it did not rapidly fade away as novae commonly do, but has ...

NASA’s Webb opens new window on supernova science

2024-06-10

Peering deeply into the cosmos, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope is giving scientists their first detailed glimpse of supernovae from a time when our universe was just a small fraction of its current age. A team using Webb data has identified 10 times more supernovae in the early universe than were previously known. A few of the newfound exploding stars are the most distant examples of their type, including those used to measure the universe's expansion rate.

"Webb is a supernova ...

May research news from the Ecological Society of America

2024-06-10

The Ecological Society of America (ESA) presents a roundup of four research articles recently published across its six esteemed journals. Widely recognized for fostering innovation and advancing ecological knowledge, ESA’s journals consistently feature illuminating and impactful studies. This compilation of papers explores how wolf reintroduction affects other carnivores, how drought and grazing snails together drive salt marsh productivity, the key to an invasive fish’s success and the plight of backyard trees, ...

Taking the fall: How stunt performers struggle with reporting head trauma

2024-06-10

In the heart-pounding action scenes of your favorite blockbuster, it's not always the A-list actor taking the risks but the unsung heroes—stunt performers—who bring those breathtaking moments to life. However, behind the glamour lies a grim reality: the reluctance of these daredevils to report head trauma, fearing it could jeopardize their careers.

In the recently released blockbuster, “The Fall Guy,” audiences get a behind-the-scenes look at what stunt professionals go through to create those most thrilling moments, and although this film celebrates these skilled professionals, it does not highlight the impact the stunts can have on their health.

Ohio ...

Income inequality and carbon dioxide emissions have a complex relationship

2024-06-10

Income inequality and carbon dioxide emissions for high-income nations such as the United States, Denmark and Canada are intrinsically linked – but a new study from Drexel University has taken a deeper look at the connection and found this relationship is less fixed, can change over time, and differ across emission components. The findings could help countries set a course toward reducing emissions of the harmful greenhouse gas and alleviating domestic income inequality at the same time.

The ...

Yuan elevated to IEEE senior member

2024-06-10

Jinghui Yuan, an R&D staff member in the Applied Research for Mobility Systems group at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory, has been elevated to a senior member of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, or IEEE.

Senior member status is the highest grade of IEEE and requires extensive experience that reflects professional accomplishments. Only 10% of IEEE’s more than 450,000 members achieve this level.

As a transportation engineer in the Buildings and Transportation Science Division, Yuan’s research focuses on intelligent transportation systems, crash risk prediction, big data analytics, deep learning, traffic simulation and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

The RESIL-Card tool launches across Europe to strengthen cardiovascular care preparedness against crises

Tools to glimpse how “helicity” impacts matter and light

Smartphone app can help men last longer in bed

Longest recorded journey of a juvenile fisher to find new forest home

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

[Press-News.org] Lab-grown ‘mini-guts’ could help in development of new and more personalized treatments for Crohn’s diseaseEpigenetic changes to DNA help explain differences in disease severity in patients