(Press-News.org) The furious exhaust heat generated by a fusing plasma in a commercial-scale reactor may not be as damaging to the vessel’s innards as once thought, according to researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL), Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the ITER Organization (ITER).

“This discovery fundamentally changes how we think about the way heat and particles travel between two critically important regions at the edge of a plasma during fusion,” said PPPL Managing Principal Research Physicist Choongseok Chang, who led the team of researchers behind the discovery. A new paper detailing their work was recently published in the journal Nuclear Fusion, following previous publications on the subject.

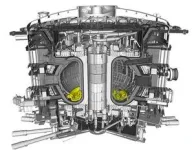

To achieve fusion, temperatures inside a tokamak — the doughnut-shaped device that holds the plasma — must soar higher than 150 million degrees Celsius. That’s 10 times hotter than the center of the sun. Containing something that hot is challenging, even though the plasma is largely held away from the inner surfaces using magnetic fields. Those fields keep most of the plasma confined in a central region known as the core, forming a doughnut-shaped ring. Some particles and heat escape the confined plasma, however, and strike the material facing the plasma. New findings by PPPL researchers suggest that particles escaping the core plasma inside a tokamak collide with a larger area of the tokamak than once thought, greatly reducing the risk of damage.

Past research based on physics and experimental data from present-day tokamaks suggested exhaust heat would focus on a very narrow band along a part of the tokamak wall known as the divertor plates. Dedicated to removing exhaust heat and particles from the burning plasma, the divertor is critical to a tokamak’s performance.

“If all of this heat hits this narrow area, then this part of the divertor plate will be damaged very quickly,” said Chang, who works in the PPPL Theory Department. “It could mean frequent stretches of downtime. Even if you are just replacing this part of the machine, it’s not going to be quick.”

The problem hasn’t stopped the operation of existing tokamaks which are not as powerful as those that will be needed for a commercial-scale fusion reactor. However, for the last few decades, there has been significant concern that a commercial-scale device would create plasmas so dense and hot that the divertor plates might be damaged. One proposed plan involved adding impurities to the edge of the plasma to radiate away the energy of the escaping plasma, reducing the intensity of the heat hitting the divertor material, but Chang said this plan was still challenging.

Simulating the escape route

Chang decided to study how the particles were escaping and where the particles would land on such a device as ITER, the multinational fusion facility under assembly in France. To do so, his group created a plasma simulation using a computer code known as X-Point Included Gyrokinetic Code (XGC). This code is one of several developed and maintained by PPPL that are used for fusion plasma research.

The simulation showed how plasma particles traveled across the magnetic field surface, which was intended to be the boundary separating the confined plasma from the unconfined plasma, including the plasma in the divertor region. This magnetic field surface — generated by external magnets — is called the last confinement surface. A couple of decades ago, Chang and his co-workers found that charged particles known as ions were crossing this barrier and hitting the divertor plates. They later discovered these escaping ions were causing the heat load to be focused on a very narrow area of the divertor plates.

A few years ago, Chang and his co-workers found that the plasma turbulence can allow negatively charged particles called electrons to cross the last confinement surface and widen the heat load by 10 times on the divertor plates in ITER. However, the simulation still assumed the last confinement surface was undisturbed by the plasma turbulence.

“In the new paper, we show that the last confinement surface is strongly disturbed by the plasma turbulence during fusion, even when there are no disturbances caused by external coils or abrupt plasma instabilities,” Chang said. “A good last confinement surface does not exist due to the crazy, turbulent magnetic surface disturbance called homoclinic tangles.”

In fact, Chang said the simulation showed that electrons connect the edge of the main plasma to the divertor plasmas. The path of the electrons as they follow the path of these homoclinic tangles widens the heat strike zone 30% more than the previous width estimate based on turbulence alone. “This means it is even less likely that the divertor surface will be damaged by the exhaust heat when combined with the radiative cooling of the electrons by impurity injection in the divertor plasma. The research also shows that the turbulent homoclinic tangles can reduce the likelihood of abrupt instabilities at the edge of the plasma, as they weaken their driving force.”

“The last confinement surface in a tokamak should not be trusted,” Chang said. “But ironically, it may raise fusion performance by lowering the chance for divertor surface damage in steady-state operation and eliminating the transient burst of plasma energy to divertor surface from the abrupt edge plasma instabilities, which are two among the most performance-limiting concerns in future commercial tokamak reactors.”

This research received funding from the DOE’s Fusion Energy Sciences and Advanced Scientific Computing Research to the SciDAC Partnership Center for High-fidelity Boundary Plasma Simulation under the contract DE-AC02-09CH11466.

PPPL is mastering the art of using plasma — the fourth state of matter — to solve some of the world's toughest science and technology challenges. Nestled on Princeton University’s Forrestal Campus in Plainsboro, New Jersey, our research ignites innovation in a range of applications including fusion energy, nanoscale fabrication, quantum materials and devices, and sustainability science. The University manages the Laboratory for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, which is the nation’s single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences. Feel the heat at https://energy.gov/science and https://www.pppl.gov.

END

New plasma escape mechanism could protect fusion vessels from excessive heat

Exhaust heat generated by commercial-scale fusion reactors may not be as damaging as once thought

2024-06-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Endocrine Society urges passage of the Right to IVF Act

2024-06-11

WASHINGTON—The Endocrine Society endorses the Right to IVF Act, which was introduced by Senators Cory Booker (D-NJ), Patty Murray (D-WA) and Tammy Duckworth (D-IL) to protect and expand nationwide access to fertility treatment, including in vitro fertilization (IVF), and urges the Senate to pass the Right to IVF Act on June 12th to ensure that the freedom to start and grow a family is protected and accessible to everyone in the United States.

Infertility affects an increasing number of individuals. ...

FAU Harbor Branch launches ‘eConch’ to grow and conserve the queen conch

2024-06-11

The queen conch (Aliger gigas) is a prized delicacy long harvested for food and revered for its beautiful shell. With a lifespan between 25 to 40 years, the queen conch is second only to the spiny lobster fishery and is the most important molluscan fishery in the Caribbean region.

Deeply rooted in the way of life in the Caribbean, many island communities depend on queen conch for their livelihoods. However, intensive fishing and habitat degradation from urbanization and climate change have caused conch populations ...

Surprisingly high levels of toxic gas found in Louisiana

2024-06-11

The toxic gas ethylene oxide, at levels thousand times higher than what is considered safe, was detected across parts of Louisiana with a cutting-edge mobile air-testing lab. The concentrations found dwarfed Environmental Protection Agency estimates for the region.

The findings, led by Johns Hopkins University environmental engineers, suggest significantly higher cancer risks for people who live near facilities that manufacture and use ethylene oxide, as well as a need for more accurate and reliable tools to monitor emissions.

“I don’t think there’s any census track in the area that wasn’t at higher risk for cancer than we would deem acceptable,” said ...

Soil bacteria respire more CO2 after sugar-free meals

2024-06-11

When soil microbes eat plant matter, the digested food follows one of two pathways. Either the microbe uses the food to build its own body, or it respires its meal as carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere.

Now, a Northwestern University-led research team has, for the first time, tracked the pathways of a mixture of plant waste as it moves through bacteria’s metabolism to contribute to atmospheric CO2. The researchers discovered that microbes respire three times as much CO2 from lignin carbons (non-sugar aromatic units) compared to cellulose carbons (glucose sugar units), which both add structure and support ...

Human evolution and online morality

2024-06-11

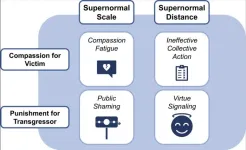

In a Review article, Claire Robertson and colleagues explore how human morality, which evolved in the context of small in-person groups, functions on the internet with over five billion users. Evolved human responses, such as compassion for victims and urges to punish transgressors, operate differently online, the authors argue. The internet exposes users to large quantities of extreme morally relevant stimuli in the form of 24-hour news and intentionally outrageous content from sometimes physically distant locations. Subjecting human brains to this ...

Price sensitivity to unhealthy foods

2024-06-11

Consumer data shows people with obesity are more price-sensitive than others when it comes to buying unhealthy foods, suggesting a food tax could be an effective public health measure. Taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages have become a commonly employed policy to improve public health. Less common are taxes on unhealthy foods, such as candy, cookies, or potato chips--and there is little data on whether such taxes would improve public health. Ying Bao and colleagues examined whether individuals of various ...

Book bans as political action

2024-06-11

In the 2021–2022 school year, schools banned books more often than ever before in United States history. Katie Spoon, Isabelle Langrock, and colleagues analyzed data from PEN America on 2,532 book bans that occurred during the year, in combination with county-level administrative data, book sales data, and a novel crowd-sourced dataset of author demographic information. The research team found that people of color are several times more likely to be the authors of banned books than White authors and that a considerable proportion of banned books, both fictional and historical, feature characters of color. About 37% of banned books were children’s ...

New study shows metabolic and bariatric surgery prevents pre-diabetes from developing into type 2 diabetes in most patients

2024-06-11

Patients with pre-diabetes and severe obesity who had metabolic and bariatric surgery were 20-times less likely to develop full-blown type 2 diabetes over the course of 15 years than patients with the condition who did not have surgery, according to a new study* presented today at the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting.

Only 1.8% of patients progressed to a diagnosis of diabetes in five years after metabolic surgery (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy), which rose to 3.3% in 10 years and 6.7% after 15 years. The protective effect against diabetes was higher ...

New studies suggest benefit of total robotic metabolic and bariatric surgery over conventional laparoscopy

2024-06-11

SAN DIEGO – June 11, 2024 – Two new studies* presented today at the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting suggest total robotic metabolic and bariatric surgery may result in shorter operative times, reduced lengths of stay and lower complications compared to laparoscopic approaches.

In one study, researchers from AdventHealth in Celebration, FL examined the outcomes of a single surgeon who performed 809 metabolic and bariatric operations – 498 totally robotic and 311 laparoscopic -- between 2020 and 2023. They found total robotic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) resulted in significantly shorter ...

Bariatric surgery more effective and durable than new obesity drugs and lifestyle intervention

2024-06-11

SAN DIEGO – June 11, 2024 – Systematic reviews* of medical literature between 2020 to 2024 show bariatric surgery, also known as metabolic or weight-loss surgery, produces the greatest and most sustained weight loss compared to GLP-1 receptor agonists and lifestyle interventions. The study was presented today at the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting.

Researchers found lifestyle interventions such as diet and exercise resulted in an average weight loss of 7.4% but that weight was generally regained within 4.1 years. GLP-1s and metabolic ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

SKKU research team unravels the origin of stochasticity, a key to next-generation data security and computing

Flexible polymer‑based electronics for human health monitoring: A safety‑level‑oriented review of materials and applications

Could ultrasound help save hedgehogs?

attexis RCT shows clinically relevant reduction in adult ADHD symptoms and is published in Psychological Medicine

Cellular changes linked to depression related fatigue

First degree female relatives’ suicidal intentions may influence women’s suicide risk

Specific gut bacteria species (R inulinivorans) linked to muscle strength

Wegovy may have highest ‘eye stroke’ and sight loss risk of semaglutide GLP-1 agonists

New African species confirms evolutionary origin of magic mushrooms

Mining the dark transcriptome: University of Toronto Engineering researchers create the first potential drug molecules from long noncoding RNA

IU researchers identify clotting protein as potential target in pancreatic cancer

Human moral agency irreplaceable in the era of artificial intelligence

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

GLP-1RA switching and treatment persistence in adults without diabetes

[Press-News.org] New plasma escape mechanism could protect fusion vessels from excessive heatExhaust heat generated by commercial-scale fusion reactors may not be as damaging as once thought